By Erica Techo

By Erica Techo

In early 2020, the federal government released its first official maternal mortality rate report in more than a decade. Numbers from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that Alabama’s maternal death rate was third highest in the nation — 36.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing PhD student Megan Mileski, MSN, RN, is serving on the committee that hopes to better understand maternal death rates, create consistent reporting practices, and hopefully determine ways to reduce the number of maternal deaths.

The Alabama Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC) first met in December 2018, when members received formal training from the CDC. In 2019, the MMRC met quarterly to review maternal deaths that occurred during pregnancy or within one year of birth in 2016 to try and determine if the deaths were preventable or not preventable and what factors contributed to the maternal deaths. It comes down to creating a better way to record and understand maternal deaths because, currently, numbers from state death certificate data are inconsistent.

“Alabama has tried this before, but there has never been such a national call for more information,” Mileski said. “In the past, committees would encounter funding issues, but the Alabama Maternal Mortality Review Committee benefits from a more sustainable, viable surge for collecting information and streamlining the data collection process. However, we are still in desperate need of funds to continue our work.”

Mileski, a fourth-year PhD student, worked in labor and delivery at UAB hospital for 15 years and is currently an Assistant Professor at the Samford University Ida Moffett School of Nursing.

Her passion for healthy births and healthy recoveries for mother and baby are leading her PhD focus and her role on the committee.

“My research focus is on African American infant mortality rates, particularly preterm birth rates, which links to maternal mortality rates,” Mileski said. “I was really passionate about this topic when I practiced and noticed how many of our African American babies were born small and too soon. The problem has been persistent, and despite efforts, we see that the racial disparities continue. Through my research, I want to look at this public health crisis in a different way.”

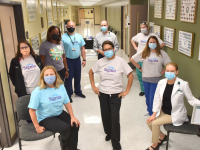

The committee includes members from a variety of backgrounds, including health care and non-health care professionals. The different perspectives come together to help create a well-rounded point of view to each case, Mileski said, and help them look at the multitude of factors at play.

“I’m proud to be one of the nurses at the table, and to be one of the voices with a high-risk background,” Mileski said. “Nurses are really the front line in labor and delivery, and in following up with the patient. The nurse has so many touchpoints with the patient, and it’s essential that we are part of this conversation.”

In 2019, the committee reviewed around 40 total cases and is creating a formal report with recommendations about how to identify vulnerable groups of mothers and to create programs and initiatives to improve outcomes. What they really need now if funding and support from the state of Alabama.

“The biggest thing at play, my ultimate desire, is helping our mothers achieve safe passage and to be able to fully recover and care for her baby after birth,” Mileski said. “No woman should expect to die as a consequence of childbirth. One death is too many, and we need to figure out ways to prevent these deaths at all levels of care and for all women.”