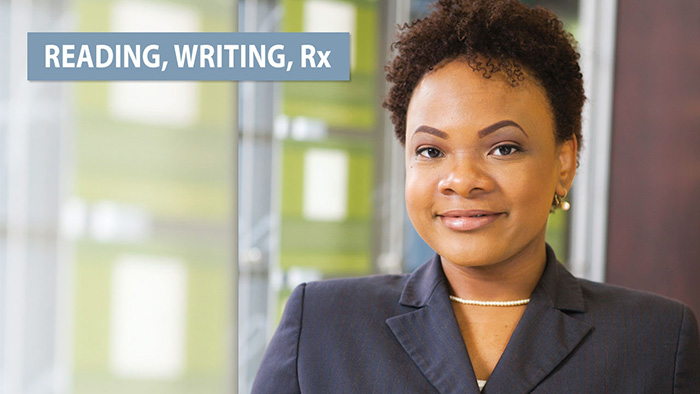

Are you fluent in health care? Can you decipher the numbers on lab reports, for example, or comprehend the information that comes with prescription medications? For many Alabamians, gaps in health literacy—the ability to understand and use health information in ways that will be most beneficial to their health—are becoming more challenging. “With health policy changes, it’s no longer enough just to understand how to manage your medical condition,” says C. Ann Gakumo, Ph.D., R.N., an assistant professor in the UAB School of Nursing. “You have to be literate about your health-care options and how to navigate a complex health-care system. It can be intimidating for lower-literate individuals.”

Gakumo’s efforts to improve health literacy have won national attention: Last year, she was one of 12 nursing educators nationwide selected for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars program, designed to cultivate promising leaders in academic nursing. The prestigious honor came with an award to support her research, which will test the power and reach of smartphones to overcome obstacles faced by some low health-literate patients. In particular, Gakumo is focusing on older African Americans with HIV and other chronic conditions such as hypertension; as a group, they are less likely to follow the treatment regimens essential to managing their blood pressure—and more likely to be hospitalized for complications from cardiovascular disease—than people of other ethnicities.

In Gakumo’s intervention, patients with a history of taking their medications consistently will assist their low health-literate counterparts, using smartphones to help them monitor their adherence to medication regimens. The clever combination of technology with old-fashioned person-to-person contact has the potential to help more patients stick to their prescribed treatment plans, Gakumo says. “Especially in rural areas, people living with HIV can tend to feel stigmatized and less connected,” she explains. “I hope that a sense of connection with peers dealing with similar issues can help patients feel more engaged and more likely to access comprehensive health care and services.” Mentors supporting Gakumo’s research award include Karen Meneses, Ph.D., R.N., FAAN, School of Nursing associate dean for research, and Michael Mugavero, M.D., M.H.Sc., director of the UAB Center for AIDS Research clinical core.

Gakumo also uses technology to teach undergraduate nursing students about health-literacy challenges they will encounter in their careers. “Our School of Nursing is known for advances in distance-accessible education, which gives me a lot of latitude in pairing my teaching with technology,” she says. In one assignment, students do some digital roleplaying. Their goal: to avoid using medical jargon as they talk with a low-literate electronic “patient.” The students also critique health-related apps to determine how appropriate they are for low-literate users. Along with nursing students, Gakumo mentors others pursuing degrees in medicine, psychology, and the health professions.

Gakumo’s introduction to health literacy gaps came early in her nursing career, when she helped patients and families wrestling with chronic illnesses in a Birmingham intensive care unit—and then again in California, as a travel nurse caring for patients who spoke little to no English. The problem hits home as well: Gakumo regularly visits her 78-year-old grandmother, a middle-school graduate with diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic health issues, to talk about her medication regimen. Every nurse has stories like these, Gakumo explains. For her, they serve as constant inspiration to investigate possible solutions, teach future health professionals, and “fully understand the role I can play in addressing this important area” of care.

Click here to see original UAB Magazine story.

• Learn more about the School of Nursing's groundbreaking research initiatives.