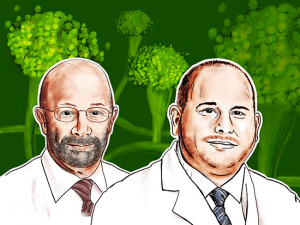

Tweets containing the words "Chinese virus" or "China virus" rose tenfold in the week after President Trump referenced the novel coronavirus as the "Chinese virus" on Twitter on March 16, compared with the week prior to the president's tweet, according to research from the School of Public Health.A new study by researchers in the UAB School of Public Health illustrates how stigmatizing language by those in power — in this case, the president of the United States — can reach across the country in a very short period of time. Henna Budhwani, Ph.D., and Ruoyan Sun, Ph.D., looked at the week before and the week after the March 16 presidential tweet calling the novel coronavirus the “Chinese virus” on his official Twitter account. How, they wondered, did other Twitter users respond?

Tweets containing the words "Chinese virus" or "China virus" rose tenfold in the week after President Trump referenced the novel coronavirus as the "Chinese virus" on Twitter on March 16, compared with the week prior to the president's tweet, according to research from the School of Public Health.A new study by researchers in the UAB School of Public Health illustrates how stigmatizing language by those in power — in this case, the president of the United States — can reach across the country in a very short period of time. Henna Budhwani, Ph.D., and Ruoyan Sun, Ph.D., looked at the week before and the week after the March 16 presidential tweet calling the novel coronavirus the “Chinese virus” on his official Twitter account. How, they wondered, did other Twitter users respond?

In their study, published on April 26 in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, Budhwani and Sun report that tweets containing the words “Chinese virus” or “China virus” rose nearly ten-fold, to 177,327 between March 19-25 from 16,535 between March 9-15, with increases across all 50 states. They mapped tweets at the state level, calculating posts per 10,000 citizens to normalize for population differences among states.

The five states with the largest increase in “Chinese virus” tweets from pre- to post-period were:

- Idaho (1,457%)

- New Hampshire (1,420%)

- Mississippi (1,387%)

- South Dakota (1,233%)

- Kansas (1,202%)

Ranked by sheer number of tweets, references to “Chinese virus” or “China virus” were most numerous in:

- California (19,442 tweets)

- Texas (14,861)

- Florida (13,070)

- New York (11,754)

- Pennsylvania (5,249)

Online social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, have become an important part of our lives, the researchers note, with millions of new posts daily. Social media also is a platform for opinion exchanges, which could translate into behavior changes, said Sun, an outcomes researcher and assistant professor in the Department of Health Care Organization and Policy. Sun has used network analysis to study how social interactions among teenagers could affect their smoking behaviors. “Unfortunately, some of these opinions could produce harmful consequences,” she said. In this study, the rise of “Chinese virus” and “China virus” on Twitter could lead to negative emotions or even hate crimes against certain groups.

"The content of the tweets was alarming," said Ruoyan Sun, Ph.D.“The content of the tweets was alarming,” Sun said. “Two tweets we cite in the manuscript are:

"The content of the tweets was alarming," said Ruoyan Sun, Ph.D.“The content of the tweets was alarming,” Sun said. “Two tweets we cite in the manuscript are:

‘Not parroting MSM’s [main stream media’s] narrative. It’s the #WuFlu #ChineseCoronaVirus #ChinaVirus’

And

‘#ChinaVirus #ChinaLiesPeopleDie.’”

The rise in “Chinese virus” or “China virus” tweets could “lead to real-life consequences for certain groups,” said Budhwani, an assistant professor in the Department of Health Care Organization and Policy. “Generally speaking, perpetuating COVID-19 related stigma could harm public health efforts related to addressing the pandemic, specifically inciting fear and increasing distrust of public health systems by Chinese and Asian Americans.”

On March 27, the FBI’s Houston office shared an intelligence report with all other FBI field offices warning that “hate crime incidents against Asian Americans likely will surge across the United States,” according to an ABC News report.

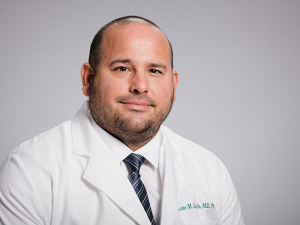

The current study is the latest in a string of research on the health effects of stigma by Budhwani. “I am keenly interested in how structural forces constrain and enable health behaviors,” she said. “We know transportation, access to care and related barriers are critical, but when we overlay social and behavioral theory, we can also include the effects of stigma, discrimination and other structural forces into our research.” For this latest study, Budhwani collaborated with Sun, who joined UAB in 2019 and has an increasing research focus related to chronic disease risk-reduction.

“Stigma is created and reinforced by those in power," said Henna Budhwani, Ph.D. "When the president of the United States references the novel coronavirus as the ‘Chinese virus’ in a presidential tweet, he is expressing his power and authority to reinforce and perpetuate stigma against those with less social power.”Budhwani’s doctoral dissertation examined the statistical relationship between discrimination and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety among immigrants to the United States. She has since published studies on the harmful effects of stigma on Muslim women in the United States, on sexual and gender minorities in the Caribbean and on people of color in the United States. She has an NIH grant that aims to increase rates of HIV testing among sexual and gender minorities in rural and urban Alabama, in part by stigma-reduction efforts. Budhwani also is the site principal investigator at UAB for the NIH-funded Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. “A critical element of the ATN’s work is stigma-reduction to address the HIV epidemic among young people,” she said.

“Stigma is created and reinforced by those in power," said Henna Budhwani, Ph.D. "When the president of the United States references the novel coronavirus as the ‘Chinese virus’ in a presidential tweet, he is expressing his power and authority to reinforce and perpetuate stigma against those with less social power.”Budhwani’s doctoral dissertation examined the statistical relationship between discrimination and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety among immigrants to the United States. She has since published studies on the harmful effects of stigma on Muslim women in the United States, on sexual and gender minorities in the Caribbean and on people of color in the United States. She has an NIH grant that aims to increase rates of HIV testing among sexual and gender minorities in rural and urban Alabama, in part by stigma-reduction efforts. Budhwani also is the site principal investigator at UAB for the NIH-funded Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. “A critical element of the ATN’s work is stigma-reduction to address the HIV epidemic among young people,” she said.

“Stigma is created and reinforced by those in power,” Budhwani said. “When the president of the United States references the novel coronavirus as the ‘Chinese virus’ in a presidential tweet, he is expressing his power and authority to reinforce and perpetuate stigma against those with less social power.”

The researchers plan to continue to monitor the ebb and flow of the use of the terms “China virus” and “Chinese virus” on Twitter. They also are using sentiment analysis and trend analysis techniques to pursue other epidemiological and socio-behavioral research questions related to COVID-19 in social media data.