When researchers from UAB and some 30 other universities and organizations gathered for the seventh Annual Translational and Transformative Informatics Symposium at Margaret Cameron Spain Auditorium last month, the hot topic was AI.

This was by design; the theme of ATTIS 2023, planned well in advance, was Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Medicine and Healthcare. “All of us probably agree that this is a golden age to be in this field,” said ATTIS 2023 Program Chair Jake Chen, Ph.D., professor of genetics, computer science and biomedical engineering at UAB, in his opening remarks.

“AI in health care is not a passing fad or blip on the radar,” said keynote speaker Trey Ideker, Ph.D., professor of medicine, bioengineering and computer science at the University of California San Diego, in a talk titled “Building a Mind for Cancer” (watch here). “Its importance for health care cannot be overstated,” Ideker said. He leads BRIDGE2AI: CELL MAPS FOR AI (CM4AI) DATA GENERATION PROJECT, part of the NIH common fund program that aims to “propel biomedical research forward by setting the stage for widespread adoption of artificial intelligence,” according to its website. Chen, among other CM4AI investigators, leads the CM4AI teaming module through a $2 million-plus grant to UAB.

Throughout the symposium, speakers demonstrated how AI can be and already is being used to predict responses to chemotherapy, find new antiviral drugs, improve the analysis of gene sequencing data and scour medical literature for new treatments for rare diseases. (See “Early health warnings, accelerating drug discovery and predicting chemo response,” below.)

But participants also acknowledged a ripped-from-the-headlines feeling to the subject matter. ChatGPT, the AI chatbot from OpenAI that took the world by storm starting in late 2022, had just been superseded by OpenAI’s latest creation, GPT–4, another massive advance.

Health care applications “too many to list”

John Osborne, Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine in the Heersink School of Medicine’s Department of Medicine, led a tutorial session (watch here) titled “Large Language Models in AI: What’s New About ChatGPT?” Osborne, who is familiar with language models from his teaching of UAB’s course in natural language processing, or NLP, gave an overview of how such models work. He displayed a chart of performance scores on a wide range of reasoning, coding, mathematics and comprehension tasks and pointed out that GPT–4 trounced not only the state-of-the-art systems designed to complete these tasks, but also handily beat ChatGPT as well.

Early health warnings, accelerating drug discovery and predicting chemo response

In a series of technical talks at ATTIS 2023 (watch here), researchers from UAB and elsewhere shared their AI work. A brief sampling:

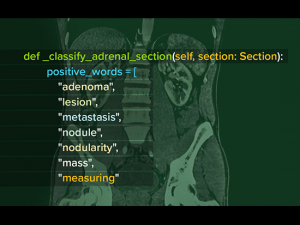

Andrew Smith, M.D., Ph.D., professor and vice chair of Innovation in the Heersink School of Medicine Department of Radiology, demonstrated how AI can be used for “opportunistic screening” — churning through images taken for other purposes in order to find warning signs of disease while adding no additional patient cost or radiation exposure. When a suspicious finding is turned up, the patient’s physician can be notified for follow-up if appropriate. One example Smith demonstrated: Chest and abdominal CT scans (more than 80,000 patients per year at UAB receive these) can flag patients at risk for a heart condition known as cardiomegaly and for abdominal aortic aneurysms, both of which can be treated with medications and other interventions.

Sixue Zhang, Ph.D., director of the Center for Computer-Aided Drug Discovery at UAB affiliate Southern Research, described SAIGE, an integrated platform for AI-aided drug discovery that is being used to predict the activity, pharmacokinetics and off-target toxicity of experimental new antiviral drugs. The tool has already helped to identify candidate compounds to inhibit alphaviruses such as chikungunya and flaviviruses including dengue and Zika.

Timothy Fisher, a Ph.D. candidate from Georgia State University working in the lab of Professor Ritu Aneja, Ph.D., in the UAB School of Health Professions, explained his research using machine learning approaches to predict chemotherapy response in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, a subtype that makes up about 15 percent of breast cancer cases and has the poorest overall survival statistics. Fisher is developing a “computational pathologist” using machine learning to identify features that predict which patients will have a positive response to chemotherapy.

“GPT–4 is significantly better than ChatGPT at doing these kinds of tasks,” Osborne said. He compared it to the arrival of the groundbreaking BERT language model from Google in 2018. “All the work you’ve been doing for the last few years, someone just … did better than you in everything,” Osborne said. “You could probably just publish a paper right now if you wanted to; you could take whatever your task is, throw it into GPT–4 and show you just beat the state-of-the-art in whatever dataset you ran it on. It’s that much of an improvement.” (See “More context,” below.)

The possible health care applications for ChatGPT, GPT–4 and other new large language models are “too many to list,” Osborne said. These include summarizing research findings at vast scale, speeding up reviews of medical charts, providing detailed explanations for billing and coding decisions, assisting physicians with writing insurance pre-approval requests, editing scientific papers, and more.

During his tutorial, Osborne demonstrated how participants could practice training their own language models using the reinforcement learning techniques that help power ChatGPT and GPT–4. He also pointed out alternative, open-source models participants could use instead, such as Stanford’s Alpaca, that are small enough to fit on a laptop and do not require access to a separate company’s servers, as do ChatGPT and GPT–4.

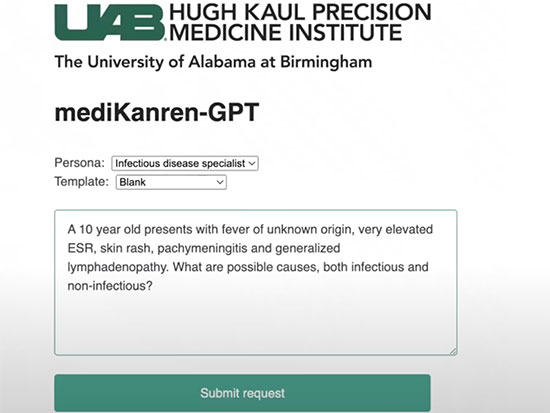

Combining logic and GPTs

Matt Might, Ph.D., director of the UAB Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute, or PMI, explained how its AI tool mediKanren identifies treatments for patients with rare diseases (read about one dramatic example in UAB News). By finding logical connections among millions of scientific papers and a number of pharmaceutical databases, mediKanren can identify ways to increase or decrease the activity of specific genes through FDA-approved drugs. The PMI team is now developing mediKanren-GPT. It combines the symbolic — logical and explainable — AI approach used by mediKanren with the powerful machine learning approach embodied in ChatGPT and other large language models such as Google’s Bard. (This machine learning approach can also be called “connectionist” because it is based on connecting layers of artificial neurons roughly inspired by the workings of the human brain.)

“The problem with large language models is that they’re about as complicated as real brains, so we don’t really know how they know what they know, and just like real brains, sometimes they make things up,” Might said. “If you ask a large language model to justify its reasoning for an assertion, it may very well just give you a plausible-looking bibliographic entry for a paper that doesn’t actually exist. So, if you take a closer look, the strengths of the symbolic approach cover the weaknesses of the connectionist approach and vice versa.”

Large language models are very good at extracting facts from scientific papers to add to the curated knowledge base that powers mediKanren, Might explained.

“It’s almost flawless at this task, so our ability to extract — or verify — structured knowledge from the literature has gone up an order of magnitude overnight," Might said. "That’s something we will be doing with mediKanren — rebuilding its structured knowledge base by having LLMs [large language models] read the literature. At the same time, mediKanren can then also verify the assertions coming out of LLMs. So, if an LLM makes a claim, then that claim can be passed to a symbolic AI for verification.”

“It’s almost flawless at this task, so our ability to extract — or verify — structured knowledge from the literature has gone up an order of magnitude overnight," Might said. "That’s something we will be doing with mediKanren — rebuilding its structured knowledge base by having LLMs [large language models] read the literature. At the same time, mediKanren can then also verify the assertions coming out of LLMs. So, if an LLM makes a claim, then that claim can be passed to a symbolic AI for verification.”

In a brief demonstration of mediKanren-GPT, Might showed how his team was able to “push facts from mediKanren relevant to a specific domain into an LLM as needed,” he said. “What that means is I can give ChatGPT a medical specialist persona like infectious disease or genetics or cardiology.”

The PMI team has several other LLM-related projects in the works, Might noted in an email following the conference. These include “having LLMs take questions in English and translate them automatically into the symbolic query language used by mediKanren” and “allowing an LLM to interactively call a tool like mediKanren when it hits the limits of its knowledge through something like a ChatGPT plug-in.”

Sharing progress and ongoing projects is part of the mission of the ATTIS symposium, said James Cimino, M.D., director of UAB’s Informatics Institute. “Given the current state of health care, it is more important than ever to have a symposium such as this that allows the open exchange of dialogue and potentially innovative ideas.”

Read more about ATTIS 2023 here.

Caution, optimism and a “productivity explosion”: Views from the front lines of AI in health care

The final session of ATTIS 2023 was a panel discussion (watch here) on the present and future of adopting AI in health care settings, led by Rubin Pillay, Ph.D., M.D., chief innovation officer for the Heersink School of Medicine and executive director of the school’s Marnix E. Heersink Institute for Biomedical Innovation. AI “is going to be a transformative force in health and health care,” Pillay said. “If you ask me, I would probably bet on the fact that AI is going to be the last great invention.”

Matt Might, Ph.D., director of UAB’s Precision Medicine Institute, noted that everybody on his team “is AI-powered at this point,” from researchers and programmers to accountants and other staff members. “We pay for the ChatGPT Plus subscription for everybody … [and] have weekly jam sessions where we show each other what we have learned how to do in the past week,” Might said. “It has been a productivity explosion … We were able to put together the draft of a grant proposal in 30 minutes, [whereas] it would take weeks to do that previously.”

Eric Ford, Ph.D., a professor with joint appointments in the School of Public Health and Collat School of Business, teaches courses on health care innovation and management. He is using ChatGPT in his courses, Ford said, “and uniformly students say, ‘I have to really frame the question well to get something [useful] back’ …. That’s a skill we’ve had a harder time teaching for many years.” This could be an overlooked benefit of widespread AI adoption in higher education in general, Ford noted. “I think we’re really in the educational realm having a great moment, where people are actually learning to ask the right question the right way and be thoughtful.”

Caution – and optimism

But there is a dramatic need for regulations to ensure that human values are reflected as AI adoption increases, said Jake Chen, Ph.D., professor of genetics, computer science and biomedical engineering at UAB and associate director/chief bioinformatics officer for the UAB Informatics Institute. “AI makes perfectly utilitarian decisions,” Chen said. “We need to regulate and be cautious.”

“The hottest topic in AI [is] ethics and governance,” Pillay agreed. “I think that is going to be the foundational principle of any AI-driven organization.” (The Marnix E. Heersink Institute for Biomedical Innovation offers an AI in Medicine Graduate Certificate, Pillay noted, and will soon offer a master’s degree program as well.)

Earlier in the discussion, Pillay noted that health care was trailing other industries in hiring workers with AI skills. But Chen said he saw benefit in the slower approach made necessary by the complexities of biology and relative expensiveness of data collection due to regulation. “AI is moving terribly fast in industries where the data are easy to obtain,” Chen said. For people working in health care, this is a “tremendous time,” he continued. “You can play in this area and learn from the best and actually think about whether you want to be … fast or you want to preserve something.”

Expanding the “usable work span” for knowledge workers

Looking to the future, Ford said that his hope “for AI is not that it needs to be at the” forefront, but that it will allow “doctors, nurses and other professionals to do what I call ‘operating at the top of the license,’ doing the work that matters.”

Might picked up on this, noting that crystallized intelligence improves with age in humans, while generative intelligence fades with time. “When you get old, you are really good at recognizing good answers, good solutions; [but] you are not as good at generating them,” Might said. “Really good generative AI … can generate lots of potential ideas and you can quickly pick out the good ones. So in some sense, knowledge workers will have their usable work span extended significantly by technology like this.”

To share comments and explore further AI-related biomedical and clinical research informatics collaboration opportunities, contact Professor Jake Chen at jakechen@uab.edu.

More context

One technical advance of GPT–4 is the vastly increased “context window” that the newer model uses — the amount of text that a model can keep in memory and reason over. “I think a big part of the improvement of GPT–4 is you have this much larger context size,” Osborne said. “What this means in practice is … if you are processing clinical text, you can read the whole note in there and do inference over the whole note. If you are reading papers on PubMed, instead of just putting the abstract in there because that is all that will fit in there, you can read the entire paper …. If you look at ChatGPT, if it is looking at a scientific paper, it is not going to get the citations right — it’s just too far outside the context window. It will make it up — hallucinate it — before it gives you the correct answer. If you have these larger context lengths, there is a lot more reasoning that can happen.”