Update: April 24, 2023 - This study is now closed to recruiting. No more participants are being enrolled.

A new UAB study is learning more about the effects of dietary salt on blood pressure, including who is most affected and the mechanisms behind it.High blood pressure — hypertension — is the leading underlying cause of death worldwide. More than 1.25 billion people have hypertension, including more than 100 million Americans. Most people worldwide eat more salt (chemically, sodium chloride) than recommended, too. Is there a connection?

A new UAB study is learning more about the effects of dietary salt on blood pressure, including who is most affected and the mechanisms behind it.High blood pressure — hypertension — is the leading underlying cause of death worldwide. More than 1.25 billion people have hypertension, including more than 100 million Americans. Most people worldwide eat more salt (chemically, sodium chloride) than recommended, too. Is there a connection?

“A number of studies link high salt intake to high blood pressure and a higher risk of premature death and cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and strokes,” said Cora Lewis, M.D., MSPH, professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology in UAB’s School of Public Health. “From randomized controlled trials, the gold-standard type of clinical study, we know that a lower-sodium diet lowers blood pressure on average. But there is wide variability in blood pressure response to salt.”

New clinical trial explores two crucial questions

Some people, for reasons not yet clear, are more salt-sensitive than others. Identifying these individuals is important, because “studies show that people who are salt-sensitive are at higher risk for mortality — death from any cause,” Lewis said.

Lewis is the UAB principal investigator for a multi-center clinical trial that is exploring two related questions:

- How common is salt sensitivity of blood pressure?

- What mechanisms can explain it?

Update: April 24, 2023 - This study is now closed to recruiting. No more participants are being enrolled.

“People who have high blood pressure are more often salt-sensitive than people with normal blood pressure,” Lewis said. Current estimates are that around half of people with high blood pressure are sensitive to salt, while that figure is only about 25 percent for people with normal blood pressure. Also, “Black people tend to be more often salt-sensitive than white people,” Lewis added.

Long-term effects of eating too much salt

“In the short term, the body has mechanisms to maintain a steady concentration of sodium in blood and tissue,” Lewis said. “If you sit down and eat a bag of salty potato chips, the extra sodium is fairly quickly excreted in the urine. There can be a lot of variability in how much salt people eat from day to day, and generally the body reacts to keep the concentration of sodium stable.”

The greater concern is the “general pattern of a person’s diet,” Lewis said. “Typically, most people eat more salt on a daily basis than is recommended. This may keep them at a steady state that promotes high blood pressure, at least in those more sensitive to dietary salt. In this study, we are really looking at the effect of multiple meals over several days, reflective of more chronic effects of different amounts of dietary salt.”

But few studies, especially in recent decades, have looked at the relationship between blood pressure and salt intake in an experimental way. Instead of relying on food diaries and spot checks of blood pressure, Lewis’ study recruited participants to eat high-salt and low-salt diets for a week each, with blood pressure measured continuously over 24 hours using a small device that participants take home.

“There has been some controversy in certain circles over the relationship between sodium intake and cardiovascular disease, at least in part because many of the studies we have are observational and are not clinical trials,” Lewis said. “This is particularly true for the larger and longer-term studies of dietary sodium and its relationship to actual cardiovascular disease outcomes. That is where our study comes in.”

How the study works

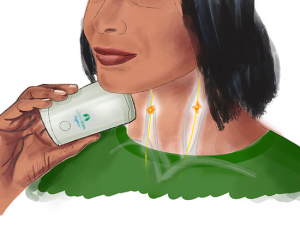

The study, which also is taking place at Northwestern University and is coordinated by a researcher at Vanderbilt University, recruited volunteers aged 50-75 who have normal blood pressure or high blood pressure that is treated and controlled. Participants begin by eating their normal diet for one week to establish baseline data on salt intake, blood pressure and more. That is followed by a week each of a high-salt diet — the participant’s normal diet plus bouillon packets to make “a salty soup that you could easily buy at the grocery store,” Lewis said — and a low-salt diet, with all food for the week provided by the study researchers. Participants also get bottled distilled water to drink, “since there can be salt in tap water, for instance if you have a water-softener system,” Lewis said.

Update: April 24, 2023 - This study is now closed to recruiting. No more participants are being enrolled.

Participants are randomized to start with the low-salt or high-salt diet, in case the order affects results. At the end of each week, participants will wear a special blood pressure monitor for 24 hours and collect urine samples for 24 hours. (Full-day urine sampling is the best way to measure how much salt a person has consumed, because it tends to be removed from the body quickly.)

Gathering crucial data

Why potassium?

In the NEJM salt-substitute study, researchers used a mixture of 75 percent sodium and 25 percent potassium. “Higher potassium intake tends to be related to lower blood pressure, and we think more potassium intake is good, as long as you have normal kidneys,” Lewis said. “People who eat a lot of salt tend to have low potassium in their diet; potassium tends to come in fruits and veggies, for example. In rural China where this trial was done, most sodium intake comes from salt added to foods during cooking and at the table. In the U.S., we get most of our salt from processed foods. So, China was the logical place to do a salt substitute trial.”

The study also is digging into possible mechanisms that could explain salt’s impact on blood pressure. Blood samples, taken during four weekly visits, will allow Lewis and her co-investigators to study how the quantities of various immune cells change with diet. “Consuming a high-salt diet might trigger inflammation,” Lewis said. “We will be studying whether the immune system responds to the high salt-containing diet compared to the low salt-containing diet.” Inflammation, the sign of an immune response, “affects the arteries and is a key factor in atherosclerosis, sometimes called ‘hardening of the arteries,’ which underlies heart attack and many strokes,” Lewis said.

Update: April 24, 2023 - This study is now closed to recruiting. No more participants are being enrolled.

Reducing salt can clearly have beneficial effects. In a large study in rural China, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2021, researchers randomized nearly 21,000 participants to use regular salt or a salt substitute with 75 percent sodium and 25 percent potassium. “Those assigned the substitute had lower rates of stroke, cardiovascular disease and death from any cause,” Lewis said. The trial results stress “that we need to know more about sodium and how it might affect the cardiovascular system. We’re working on that in this study of salt sensitivity of blood pressure.”

CARDIA sheds more light on salt and blood pressure

In the mid-1980s, researchers at UAB and in three other cities enrolled more than 5,000 young people, ages 18-30, in a study designed to look at the development of cardiovascular disease and risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease. The study is known as Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, or CARDIA. “Our participants were randomly selected from the city, and we have been following them ever since,” Lewis said.

In addition to known clinical risk factors, such as high blood pressure, the researchers have looked at what are called subclinical measures, which “occur earlier than but are related to clinical disease,” Lewis said. One of these measures is the mass, or weight, of the heart’s left ventricle.

“The left ventricle is the main pumping chamber of the heart,” Lewis said. Its mass can be measured with an echocardiogram, which is “basically an ultrasound of the heart,” she explained. “High left ventricle mass is related to a greater risk of various forms of cardiovascular disease, like heart failure.” By collecting urine over 24 hours from participants, the researchers were able to see how much salt they typically ate. The researchers then compared echocardiograms from the same participants taken five years apart and correlated the findings with the participants’ salt intake. “Few of them had high blood pressure,” Lewis said, but “nevertheless, higher sodium and less potassium in the urine was related to higher left ventricular mass at both times the echo was done. So even in healthy young adults, there are some findings that indicate a potential for higher risk of later cardiovascular disease.”

Today, Lewis and her fellow researchers are in the midst of collecting data for Year 35 of the CARDIA study. “We are now coming into the time of the participants’ lives when clinical cardiovascular disease will occur more frequently and will give us more opportunities to study how cardiovascular disease occurs over the life course,” Lewis said. “It is a very exciting time for the study scientifically, although it makes me sad that these things are happening to the participants.”

CARDIA participants are being enrolled in the salt sensitivity of blood pressure study, Lewis says. “No one has studied this in a cohort like the CARDIA study that has been following participants for a long time,” she said. “So we don’t know what early-life factors might be related to salt sensitivity of blood pressure in middle age.” In addition, the study is also enrolling from the general population of the Birmingham area.