When people lose weight, their energy needs drop more steeply than expected, due to a phenomenon called metabolic adaptation. This well-known yet little-studied effect is often blamed for long-term weight regain, but UAB researchers have found no evidence to support that. The questions are becoming more pressing as potentially millions of people take drugs such as Ozempic that can lead to short-term weight loss but long-term regain when discontinued. It is one of the most controversial issues in the obesity field: a concept that goes by many names, including metabolic adaptation, adaptive thermogenesis and, most snappy of all, “hibernation mode.”

When people lose weight, their energy needs drop more steeply than expected, due to a phenomenon called metabolic adaptation. This well-known yet little-studied effect is often blamed for long-term weight regain, but UAB researchers have found no evidence to support that. The questions are becoming more pressing as potentially millions of people take drugs such as Ozempic that can lead to short-term weight loss but long-term regain when discontinued. It is one of the most controversial issues in the obesity field: a concept that goes by many names, including metabolic adaptation, adaptive thermogenesis and, most snappy of all, “hibernation mode.”

“Imagine a person who is 220 pounds and has energy needs of 2,500 calories per day,” said Cátia Martins, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Nutrition Sciences in the UAB School of Health Professions. “They decide to lose weight and manage to lose 22 pounds, so now they are 198 pounds. You would expect that the person needs less energy, maybe that their energy needs went to 2,200 calories. But when we measure this in a metabolic chamber for 24 hours, we find that the person needs only 2,000 calories. There is a gap between measured energy expenditure and the energy expenditure we were expecting.”

This exaggerated reduction in energy expenditure after weight loss is called metabolic adaptation (or, to be more specific, adaptive thermogenesis; but we’ll go with the first term). Of all the mysteries in nutrition science, of which there are many, this may be one of the most hotly debated. According to Martins, who specializes in studying metabolic adaptation, it also is one of the most misunderstood topics in the field.

“Just no evidence whatsoever”

When you go on a diet to lose weight, does your body fight back? It’s an intriguing idea, and one that could explain the depressing statistics around weight loss. In a 2001 meta-analysis of 29 studies of long-term weight loss, more than half of the lost weight was regained within two years, and by five years that number was 80 percent. But is metabolic adaptation really to blame?

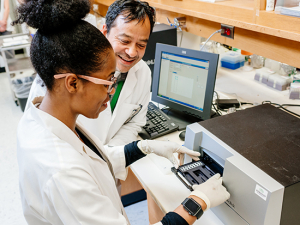

Cátia Martins, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Nutrition Sciences, has been teasing apart the mysteries of metabolic adaptation for the past 10 years, first in Norway and, since 2020, at UAB, often working closely with UAB colleagues Barbara Gower, Ph.D., and Gary Hunter, Ph.D.“There is this idea everywhere from patients to clinicians, to researchers that the main reason people regain weight after weight loss is because the body fights back,” Martins said. “But not one study has shown a link between metabolic adaptation and weight regain. There is just no evidence whatsoever.”

Cátia Martins, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Nutrition Sciences, has been teasing apart the mysteries of metabolic adaptation for the past 10 years, first in Norway and, since 2020, at UAB, often working closely with UAB colleagues Barbara Gower, Ph.D., and Gary Hunter, Ph.D.“There is this idea everywhere from patients to clinicians, to researchers that the main reason people regain weight after weight loss is because the body fights back,” Martins said. “But not one study has shown a link between metabolic adaptation and weight regain. There is just no evidence whatsoever.”

Martins has been teasing apart the mysteries of metabolic adaptation for the past 10 years, first at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim and, since 2020, at UAB, often working closely with UAB colleagues Barbara Gower, Ph.D., and Gary Hunter, Ph.D. “We have shown with different datasets that the magnitude of metabolic adaptation following weight loss is not a predictor of weight regain at up to two years follow-up,” Martins said.

Metabolic adaptation linked to more trouble with weight-loss goals

This is not to say that metabolic adaptation has no role in the struggle for weight loss. In a 2022 paper in the journal Obesity, “we found that individuals with a greater magnitude of metabolic adaptation during weight loss are those who require more time to reach their weight-loss goals and lose less weight and fat mass in response to a low-energy diet,” Martins said. “It could be a combined physiological response that makes some individuals more resistant to weight loss.” For example, a 2023 paper in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition by Martins and colleagues reported that metabolic adaptation is associated with a greater increase in appetite following weight loss — but not weight regain.

It is important to understand exactly what is happening in metabolic adaptation, including why findings in the field tend to bounce around, Martins notes. “In all of the studies, half don’t show metabolic adaptation and half do,” she said. Some show a large effect. Others, to quote the title of one of Martins’ papers in 2020, find that “metabolic adaptation is an illusion” caused by how different studies measure body composition and energy expenditure. When she and her colleagues give study participants a month following weight loss for their bodies to adapt, metabolic adaptation falls sharply, averaging only a few dozen calories per day change from pre-weight loss measures (this 2020 paper offers one example).

The methodologies of studies also contribute to the illusion, Martins says. Most studies use a two-compartment model to measure weight loss: fat-free mass (water, bones, muscle, internal organs, etc.) and fat mass (fat). Other studies add a third compartment, using DXA scans to tease out bone mineral content from the other fat-free mass components. “But that still leaves muscle, organs and water,” Martins said. “The problem is that we are assuming the changes in these compartments are proportional.”

Detailed studies show that is not the case, Martins noted: “Some people lose more organ and less muscle. Weight loss is followed by a reduction in several organ sizes, including the heart, pancreas and kidneys.” (This paper led by researchers in New York, reports that, in participants who lost 11 percent of body weight, heart mass decreased by 26 percent and the kidneys by 19 percent.) And it is important to note that the metabolic rate of organs is much higher than that of muscles, Martins says. “For some organs, it is up to 20 times higher. The problem is we do not have any studies looking at metabolic adaptation at the level of total energy expenditure with prediction models looking at the different components of fat-free mass. That would require MRI.”

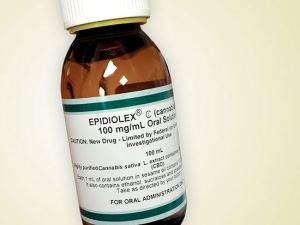

The new study proposed by Martins and Fernando Bril, M.D., will test a diet intervention based on the appetite-suppressant effects of a low-carb ketogenic diet in patients who have lost at least 10 percent of body weight on semaglutide (Ozempic) or other GLP-1 agonist drugs. The chief mechanisms of action of these drugs "seem to be reducing appetite and food intake,” Martins said. “Can we have a dietary intervention that mimics these effects?”

Two new proposed studies

This is exactly what Martins has proposed in a pending grant application to the NIH. “I want to quantify all of these things: total energy expenditure measured in a metabolic chamber and body composition using MRI and DXA, to come up with prediction models based on changes in fat, muscle and organ mass,” she said. “In my understanding, that would be the ultimate study required to answer all of these questions.”

Ideally, weight loss would be targeted as much as possible to fat loss — and to addressing the hunger that makes diets so difficult to stick with. Martins has another proposal under consideration for a clinical trial studying this in patients who have used new GLP–1 agonist drugs such as Ozempic to lose weight but stopped using them. “These new anti-obesity drugs produce weight loss similar to bariatric surgery — up until now, the gold standard treatment for obesity — but with lower side effects,” Martins said.

The drugs are expensive and in short supply, however, and the effects of long-term — potentially lifelong — use of GLP–1 agonists is unknown. “When individuals stop taking these drugs, they experience weight regain of up to two-thirds of the initial weight loss one year after stopping,” Martins said. “We need to start exploring what are the best lifestyle interventions to offer to these patients.”

Martins’ preliminary research on low-carb ketogenic diets shows that they do not trigger the upregulation of the hunger hormone ghrelin that is normally seen when dieting. “As long as the person is ketotic, ghrelin and subjective hunger feelings do not increase,” Martins said. “But no studies have been done on ketogenic diets with weight-loss maintenance, only during weight loss.”

The new study proposed by Martins and Fernando Bril, M.D., assistant professor in the Department of Medicine’s Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, will test a diet intervention based on the appetite-suppressant effects of a low-carb ketogenic diet. “The main mechanisms of action of these GLP–1 agonist drugs seem to be reducing appetite and food intake, even though energy expenditure might also be involved,” Martins said. “Can we have a dietary intervention that mimics these effects?” A ketogenic diet gets most of its calories from fat, with the goal of triggering ketosis, when the body uses fat as its main energy source.

Martins’ preliminary research on low-carb ketogenic diets shows that they do not trigger the upregulation of the hunger hormone ghrelin that is normally seen when dieting. “As long as the person is ketotic, ghrelin and subjective hunger feelings do not increase,” Martins said. “But no studies have been done on ketogenic diets with weight-loss maintenance, only during weight loss.”

The researchers aim to recruit participants who have lost at least 10 percent of body weight on semaglutide (Ozempic) or other GLP–1 agonists but have stopped taking the drugs because they reached their weight-loss goal, they lost insurance coverage or for other reasons.

“We plan to put participants through a two-week weight maintenance diet and then randomize them to a low-carb ketogenic diet or standard care (a low-fat diet) for 12 weeks, with all food provided,” Martins said. “This will be followed by a six months follow-up with dietary prescription to look at the feasibility of these diets in real life. Our hypothesis is the participants on the low-carb ketogenic diet will not increase food intake, while it will be the opposite with the participants on the low-fat diet. Evidence does show that low-carb ketogenic diets buffer appetite and increase energy expenditure, which could favor weight-loss maintenance. We will see.”