Working with faculty in the dermatology department, third-year medical student Matthew Kiszla analyzed results from nine recent studies of tattoo inks for a paper published in February. “Unsafe levels of restricted elements continue to be detected across studies," they wrote. Kiszla is looking to expand this ink analysis in collaboration with tattoo artists and researchers alike.

Working with faculty in the dermatology department, third-year medical student Matthew Kiszla analyzed results from nine recent studies of tattoo inks for a paper published in February. “Unsafe levels of restricted elements continue to be detected across studies," they wrote. Kiszla is looking to expand this ink analysis in collaboration with tattoo artists and researchers alike.

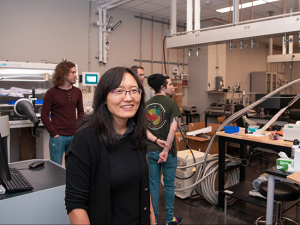

ANDREA MABRY | University RelationsThere is an open secret among tattoo artists, dermatologists and the small group of researchers studying the effects of tattoo ink: red causes the most problems.

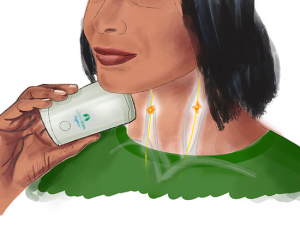

Problems? There are rashes — itchy, sometimes painful and occasionally disfiguring — which can assume fantastical shapes. Ink reactions also include pseudolymphomas — benign swellings around lymph nodes that resemble cancers of the lymph system. Both rashes and pseudolymphomas are symptoms of an allergic reaction. They are not unique to red ink, but red is the most likely culprit.

Doctors are now more likely to see tattoo complications than ever before. Thirty percent of Americans have at least one tattoo, up from 21 percent in 2012, according to a 2019 poll. A separate study in 2017 estimated the range of post-tattoo complications at anywhere from 2 percent to 30 percent; in that paper’s review of patient cases in Finland, 75 percent of allergic reactions were against the red color.

Until the mid-20th century, the reason for red’s ravages was clear: Red tattoo inks often contained mercury. But as the adverse effects of mercury and other metals became widely known, tattoo artists avoided these inks and manufacturers turned to alternative formulas. Today, manufacturers have largely switched to inks colored by organic compounds instead of compounds including heavy metals, and recent studies have found low concentrations of mercury in commercial inks.

It does not matter. Red ink is still the most likely color to cause skin problems. Why?

Red tattoo inks are the most likely to cause health complications, including rashes and pseudolymphomas, both symptoms of an allergic reaction.

Red tattoo inks are the most likely to cause health complications, including rashes and pseudolymphomas, both symptoms of an allergic reaction.“I just had to know why”

Tiffany Mayo, M.D., associate professor and director of the UAB Department of Dermatology’s Clinical Research unit, discussed this puzzle last year during a lecture to third-year students at the UAB Heersink School of Medicine. Her description and slides immediately caught the attention of Matthew Kiszla, an artist and son of an artist who had cheekily listed a book that he and his mother illustrated among the publications on his med school application. (“Publications,” for medical students, usually means scientific articles.)

Tattoos and adverse reactions: What can a consumer do?

“I would encourage anyone experiencing an adverse reaction to a tattoo to report the event and to seek out a dermatologist at an academic medical center,” Kiszla said. “The reactions should be reported to both the tattoo artist and the Food and Drug Administration” by phone (800–332–1088) or online. It is important to know the brand and name of the specific ink or inks used, he notes, because the FDA needs to link complaints to a specific product.

Treatments can vary because “there is such a diversity in the kinds of rashes that emerge from reactions to the many ingredients that collectively make up tattoo ink,” Kiszla said. The UV radiation from sunlight can trigger reactions, so avoiding sun exposure to the affected area can help in managing the symptoms.

“I am a very visual person,” Kiszla said, and even though he does not have any tattoos himself, “that attracts me to tattoos and also to dermatology, with its vivid, dramatic rashes.” Plus, Kiszla was an undergraduate chemistry major. The chemical mystery that Mayo described was irresistible, he said: “I just had to know why.”

Kiszla’s interest has become a passion to understand the effects of tattoo inks on human health and to advocate for increased attention to safety. This February, Kiszla, Mayo and another member of the Department of Dermatology, Professor Craig Elmets, M.D., synthesized results from nine recent studies of tattoo inks worldwide in a review article published in the journal Chemosphere. “Unsafe levels of restricted elements” — including chromium, cadmium, barium, arsenic and zinc — “continue to be detected across studies, warranting further investigation under a regulatory lens,” they wrote.

Although the “United States is the world’s foremost producer of tattoo inks,” they are “virtually unregulated” at a national level, Kiszla said. Tattoo inks “can be formulated with a wide range of pigments, preservatives, solvents and other contaminants,” he noted, and these “have been associated with rashes that range from transient to disfiguring.” And there may be other, hidden effects as well. “The potential systemic implications are unknown,” Kiszla said. “While researchers have found that ink can travel from its site of injection via the lymphatic system and be collected into lymph nodes, they have yet to determine whether this concentration of toxins poses any increased risk.”

Although the “United States is the world’s foremost producer of tattoo inks,” they are “virtually unregulated” at a national level, Kiszla said.

Although the “United States is the world’s foremost producer of tattoo inks,” they are “virtually unregulated” at a national level, Kiszla said. Choosing a tattoo artist: experience counts

“Given the lack of formal research and regulation on tattoo inks in the United States, artists’ experience working with inks is extremely valuable,” Kiszla said. “Their professional success is dependent on customer satisfaction.”

Tattoo artists are educated on infectious risks associated with body art by way of bloodborne pathogen training programs, Kiszla points out. And tattoo artists “are certainly more regulated than the manufacturers of their ink,” he said. “In the state of Alabama, artists must adhere to strict guidelines regarding their practice and facilities. They must maintain both an annual operator permit and a facility license with the Alabama Department of Public Health in order to practice. These certifications must be clearly displayed in any body art facility.”

Coincidence or something more?

Europe, the world’s second-largest market for tattoo ink manufacturers, leads the way “in terms of research and regulation,” Kiszla said. A series of resolutions introduced in Europe starting in 2003 set maximum allowed concentrations for tattoo ink ingredients; in 2022, these guidelines became binding on all members of the European Union. Nearly all research on the chemical makeup of tattoo inks has been done at European universities, Kiszla notes. In their Chemosphere paper, Kiszla, Mayo and Elmets compared these new European regulations with the concentrations of metals found in tattoo inks as reported in published studies.

Now Kiszla has turned his attention to organic inks. He is currently writing a paper on azo dyes with Lauren Kole, M.D., an assistant professor in the UAB Department of Dermatology — who, like Kiszla, holds an undergraduate degree in chemistry. Organic azo dyes are the new standard for tattoo inks as the industry has shifted from metal-based inks. “Warm tones — yellow, orange and red — have a high concentration of these azo structures,” Kiszla said.

The fact that red inks still cause the most adverse reactions, as they did in the days of mercury, “could just be a coincidence,” he added. “But there is not yet enough data to be sure.”

The fact that red inks still cause the most adverse reactions, as they did in the days of mercury, “could just be a coincidence,” Kiszla said. “But there is not yet enough data to be sure.” He hopes to help address this problem by collaborating with tattoo artists and specialists in chemical analysis.

The fact that red inks still cause the most adverse reactions, as they did in the days of mercury, “could just be a coincidence,” Kiszla said. “But there is not yet enough data to be sure.” He hopes to help address this problem by collaborating with tattoo artists and specialists in chemical analysis.Tattoo research needs collaborators

While the published studies that Kiszla, Mayo and Elmets evaluated did include some commercial tattoo inks, they were not comprehensive. With grant support and access to specialized testing equipment from the University of Alabama’s College of Community Health Sciences, Kiszla aims to analyze more tattoo inks. He hopes to work with tattoo artists in the community on the project. “I encourage any tattoo artists who are interested in evaluating their inks for contaminants to contact me,” he said. Kiszla also is currently looking for collaborators in UAB’s departments of Pharmacology and Toxicology and Chemistry who can help him properly prepare samples and interpret their test results.

“Ultimately, I want to support the development of safer tattoo inks,” Kiszla said. “My goal is not to impinge on artistic expression but to make body art as safe as possible and as well understood as possible.”

Is he open to getting a tattoo? “Once we finally identify those inks that are safer,” Kiszla said. “If I find that safe ink, I will have to get one. How could I not?”

Geopolitics and tattoo ink exports

Kiszla is working on yet another project related to tattoo inks: an analysis of how European regulatory changes will affect the behavior of U.S.-based manufacturers.

“Before 2020, these ink manufacturers just had to worry about inorganic components” in their products, Kiszla said. “Now, as of about 2020, these manufacturers who have really moved to organic colorants have to worry about how these compounds decay in the skin as well. The question going forward is, when these companies realize that they may need to very quickly adjust what is in their inks, does that lead to two different stockpiles of ink — one that is less safe, sold in countries like the United States with less regulation, and another, safer stock for the European market? That is the question I want to address.”