Research by UAB's Emma Sartin, Ph.D., MPH, and colleagues has found that two-thirds of parents of teens with autism are interested in them learning to drive, but only a third of those teens actually become licensed, even though those who do learn to drive "feel more empowered to be employed, go to school and so on," Sartin said. "They also have much more self-confidence and optimism about the future.”In a major 2017 study, the largest of its kind, researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia found that only a third of eligible adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and no intellectual disability acquired a driver’s license, with the majority doing so at age 17.

Research by UAB's Emma Sartin, Ph.D., MPH, and colleagues has found that two-thirds of parents of teens with autism are interested in them learning to drive, but only a third of those teens actually become licensed, even though those who do learn to drive "feel more empowered to be employed, go to school and so on," Sartin said. "They also have much more self-confidence and optimism about the future.”In a major 2017 study, the largest of its kind, researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia found that only a third of eligible adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and no intellectual disability acquired a driver’s license, with the majority doing so at age 17.

“It is really important to have access to a vehicle in this country,” said Emma Sartin, Ph.D., MPH, assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Organization at the UAB School of Public Health. “People without a personal vehicle have worse health and quality of life outcomes, even in places where there are public transportation options.” The effect of not having a car is even more magnified in vulnerable populations, who may already be predisposed to poor health and wellness because of other factors.

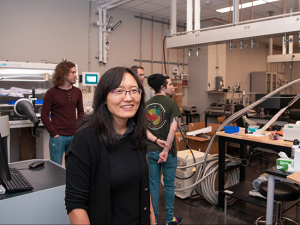

Sartin is principal investigator on a major grant from the Department of Defense to address this issue. She and colleagues are developing a virtual assessment to help autistic individuals and their parents decide whether they are ready to drive. Sartin joined UAB in August from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where she was mentored by Allison Curry, Ph.D., MPH, lead author on that 2017 driving study and several subsequent studies of driving in autistic individuals. Those include research on barriers preventing these individuals from learning to drive and their driving records post-licensure.

Just as safe behind the wheel, with a higher quality of life

A state-level analysis of crash records by Curry and Sartin found that newly licensed autistic individuals “crashed at the same rates or lower than those of their age and experience,” Sartin said. There were differences, however. “The crashes they were involved in were more likely to be when they needed to interpret other road users’ actions — in making a left turn or negotiating around a pedestrian, which calls for understanding implicit body cues,” Sartin said. This means that autistic drivers have unique training considerations.

Emma Sartin, Ph.D., MPH, is is leading a Department of Defense-funded project that is developing a virtual assessment to help autistic individuals and their parents decide whether they are ready to drive.In the team’s studies, autistic teens report that, once they are licensed, they “have much higher quality of life outcomes,” Sartin said. “They feel more empowered to be employed, go to school and so on. They also have much more self-confidence and optimism about the future.”

Emma Sartin, Ph.D., MPH, is is leading a Department of Defense-funded project that is developing a virtual assessment to help autistic individuals and their parents decide whether they are ready to drive.In the team’s studies, autistic teens report that, once they are licensed, they “have much higher quality of life outcomes,” Sartin said. “They feel more empowered to be employed, go to school and so on. They also have much more self-confidence and optimism about the future.”

Could families be dissuading teens from driving? The opposite was true in her research, Sartin notes. “One thing found early on in this research that was striking was that most parents were interested in their teens’ learning to drive,” Sartin said. Across several survey studies, two-thirds of parents were interested in their autistic teens’ driving. But as stated earlier, only a third actually become licensed.

One barrier was clear: Families said they were not sure how to determine whether their teens were good fits for driving, or whether they were ready to start practicing behind the wheel. They were most likely to turn to their child’s pediatrician or primary care provider for help; unfortunately, Sartin and Curry found in a survey that 92 percent of providers are not comfortable or knowledgeable enough to guide these decisions. What is worse is that most do not refer families elsewhere for help. “So that becomes a dead end for those families,” Sartin said. Further, in their interviews most caregivers reported spending “hours and hours” trying to find guides or resources to help them make these decisions. “There’s no one place where families receive clear guidance about how to make transportation decisions for their autistic teen,” Sartin said. Families often rely on testimonials or firsthand accounts shared by others in the autism community, or power through in a “trial by fire.” Differences in laws and services available to families further complicates things across state lines.

Certified driver rehabilitation specialists can help

There is a group that can help, however: certified driver rehabilitation specialists. “They tend to be occupational therapists with a health care background who have training in conducting driving assessments and driver training,” Sartin said. Many focus on older drivers and people who are recovering from strokes, “but there are some with a focus on helping people with neurodivergent differences learn how to drive.”

There are not many of these specialized driving instructors, though. In New Jersey, which has some of the highest rates of autism incidence in the country, there were only six such instructors identifiable online, Sartin says. And there are fewer than 350 practicing nationwide. Also, “a driver assessment tends to take three to six hours in person, and it can be expensive.” The limited number of professionals working in this field means the waiting list for an appointment can be as long as two years.

“What we saw was this bottleneck effect, with a lot of teens who are ready to begin driving waiting a long time and missing key resources and opportunities that are available only at certain ages or milestones,” said Sartin. “Also, for teens who weren’t ready to start driving, having a formal assessment can help families create plans and training goals to either better prepare them for driving in the future or identify alternative types of transportation that may be a better fit.”

Addressing a bottleneck with virtual driving assessments

Sartin’s three-year, $648,000 grant from the Department of Defense aims to address this situation, and a related issue: “There is no standardized driving assessment for neurodivergent individuals in the field,” Sartin said. “Each of these specialists is doing what they think is the right thing, but we aren’t sure which of these elements maps to a successful driver right now. If we can streamline assessments so they are quicker, that will drive down the costs so the specialists can see more people.”

Sartin is working with Curry at CHOP, and with a company called Minnesota Health Solutions and the nonprofit Driver Rehabilitation Institute on the research.

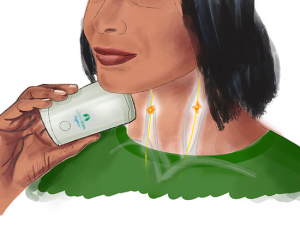

The virtual assessment will look at individuals’ levels of independence in other daily tasks, like preparing food and doing laundry. It also will test their responses to virtual activities the teen will complete during a virtual drive. For example, using real-world videos of carefully planned driving routes, they will be asked to identify whenever they see brake lights on the car ahead or notice pedestrians approaching the street. “This gets into executive functioning,” Sartin said. “We want to know ‘are they prepared to process and prioritize all of the visual, audio and social stimuli that drivers need to process?’”

Sartin and Curry are committed to creating resources for families to help them understand their options and ways to increase their loved ones’ chances of success in driving. “We have created an online 10-item screener to determine whether you are even ready for the assessment,” Sartin said. “If not, we say, ‘Based on your answers, here are some things you can work on in the interim.’ We just wrapped up a study developing those questions and are now validating it.”

Sartin and Curry are also working on interventions for individuals who are not going to drive, including “figuring out bus systems, how to be a pedestrian or cyclist, or how to use Uber,” she said. “The long-term goal is a coordinated program that has all of this information in one place.”

To learn more, see the research team’s website at https://injury.research.chop.edu/research/young-driver-safety-research/driving-neurodevelopmental-differences.