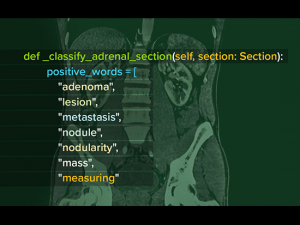

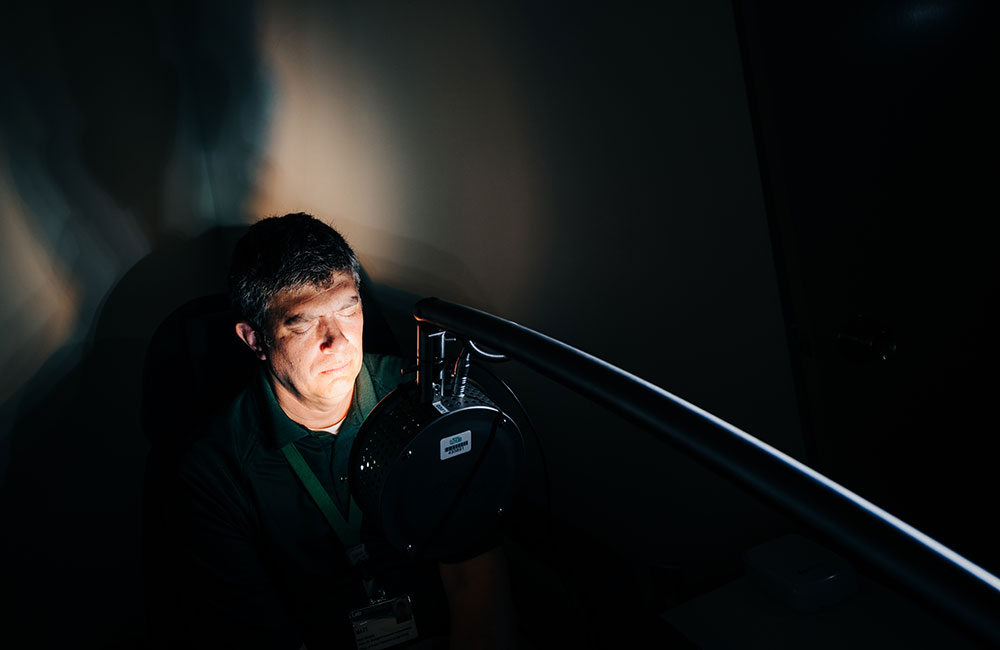

The Alabama BRAIN Lab is testing devices including this app-controlled LED lamp, which can emit light in a range of colors and frequencies to increase attention (among other uses).

The Alabama BRAIN Lab is testing devices including this app-controlled LED lamp, which can emit light in a range of colors and frequencies to increase attention (among other uses).ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

William “Jamie” Tyler, Ph.D., specializes in neuromodulation — creating technology that uses electrical currents or sound waves to non-invasively reach inside the brain and enhance human performance. Using his devices, people report learning faster, feeling better, focusing harder and blocking out pain.

Tyler has spent the first part of his career proving that his ideas are 1) safe and 2) not science fiction. Many of his projects are so ambitious that they found their natural backer in DARPA, the U.S. military’s R&D arm, which specializes in “making the impossible possible.”

Tyler has adopted that motto as his own. After earning his Ph.D. in neuroscience (2003) and his undergraduate degree (1998) at UAB — while playing offensive line for Blazer Football — Tyler has worked and taught at Harvard, Virginia Tech and Arizona State, with several stints in between as a startup founder in Boston and elsewhere. (He has founded five companies and has 45 patents so far.)

Now, drawn back to UAB by its new doctoral program in neuroengineering, Tyler is on a mission to bring neuromodulation to the masses. “I have always done that for the top 1 percent — elite athletes and members of the military,” he said. “Can we apply these technologies to medicine and help everyone become better?”

This is the overarching question that Tyler and his team are tackling in his Alabama BRAIN Lab. (BRAIN stands for Bridging Resources and Advancing Innovations in Neurohealth.) “We’re focused on the brain health of the population — everybody in Alabama,” said Tyler, who is a professor in the School of Engineering's Department of Biomedical Engineering and helps lead the Neuroengineering program. He also has appointments in the Heersink School of Medicine’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and in the Department of Occupational Therapy in the School of Health Professions.

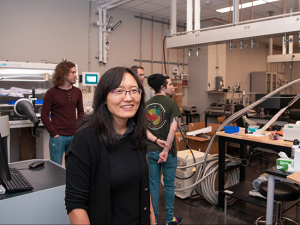

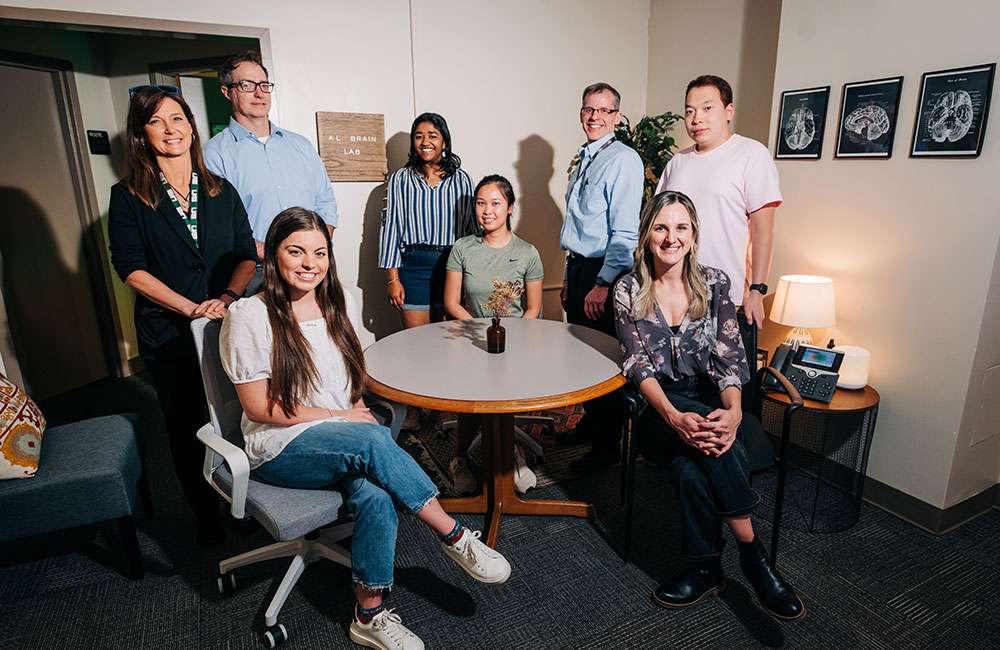

Jamie Tyler, Ph.D. (standing, second from left), and the Alabama BRAIN Lab team. Seated, left to right: Ashton Weber and Melissa Do, graduate students in neuroengineering; Alexandra Evancho, DPT, research assistant professor and lab manager. Standing, left to right: Wendy Reed, Ph.D., MPH, the lab's director of communications and engagement; Tyler, professor and lab director; Marianne Abraham, undergraduate student in biomedical engineering; Keith McGregor, Ph.D., associate professor and research director in the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences; Alibek Sartayev, graduate student in biomedical sciences.

Jamie Tyler, Ph.D. (standing, second from left), and the Alabama BRAIN Lab team. Seated, left to right: Ashton Weber and Melissa Do, graduate students in neuroengineering; Alexandra Evancho, DPT, research assistant professor and lab manager. Standing, left to right: Wendy Reed, Ph.D., MPH, the lab's director of communications and engagement; Tyler, professor and lab director; Marianne Abraham, undergraduate student in biomedical engineering; Keith McGregor, Ph.D., associate professor and research director in the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences; Alibek Sartayev, graduate student in biomedical sciences.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Safe therapies at scale

Tyler sees his lab providing a gateway to experimental therapies that have been proved to be safe but are out of reach of the vast majority of patients. The average new device or therapy takes 17 years to make it out of a lab and into clinical use, he points out. Tyler’s idea is to allow patients to take part in research trials of promising therapies at a much larger scale than is typical. This will help more patients find relief or see improvement, and more quickly identify which therapies work and which do not — or, perhaps as likely, identify the specific population in which a device is helpful, and those where it is not.

That is why he chose to be affiliated with the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tyler said. “It is where you see the most interaction with patients — in physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy.” The Alabama BRAIN Lab is strategically located in the UAB Spain Rehabilitation Center, just down the hall from the Acute Speech Therapy and Rheumatology clinics and a short elevator ride away for patients in Spain Rehab’s Brain Injury Clinic, Cancer Rehabilitation Program, physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech-language therapy services, and the Orthotics and Prosthetics Lab, to name just a few of the specialized clinics in the same building.

“Patients are already in the building for their therapy appointments,” Tyler said. “We can invite them to participate in our research.”

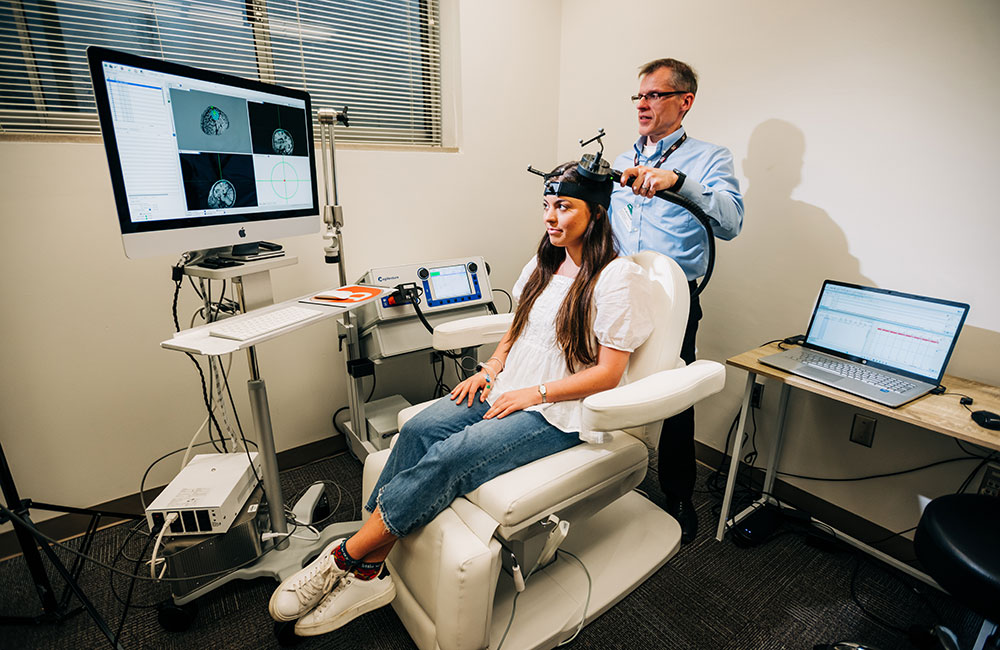

McGregor and Weber demonstrate the lab's transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device. The machines ar e FDA-approved for treating depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and headache pain. McGregor uses TMS and other technologies to study brain function.

McGregor and Weber demonstrate the lab's transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device. The machines ar e FDA-approved for treating depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and headache pain. McGregor uses TMS and other technologies to study brain function.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Gateway to bioelectronic medicine

Tyler is a world-renowned expert and pioneer in two much-talked-about, non-invasive neuromodulation therapies: focused ultrasound and vagus stimulation. Both are highly promising tools of bioelectronic medicine, which hopes to treat disease by modulating the nervous system with electricity or pressure rather than drugs. “You could replicate the effects of a drug without the side effects,” Tyler said.

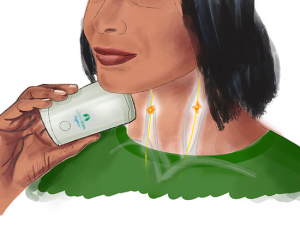

The industrial giant GE and university partners have demonstrated that they can use focused ultrasound, or FUS, to non-invasively prevent or reverse the onset of diabetes in animal models. Others have used it to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Stimulation of the vagus nerve, particularly through the ear (known as transcranial auricular vagus nerve stimulation, or taVNS) is already FDA-approved for the treatment of depression and headache. Tyler has designed taVNS devices to treat anxiety and sleep problems in people with autism spectrum disorder, help Department of Defense employees learn foreign languages more quickly, and enable a veteran with crippling PTSD to take part in a high-stakes putting tournament. (For that last story, watch “Mind Gurus,” a documentary from ESPN Films. Tyler’s section begins at 12:00.)

The Alabama BRAIN Lab already has trials underway or in the final planning stages for FUS and taVNS. The lab is collaborating with Steven Rothenberg, M.D., assistant professor in the Department of Radiology, to use FUS to treat the spinal cord to relieve pain. Another study is using taVNS to see if it can help improve sleep in patients with breast cancer who are in palliative care.

A transcranial auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) device designed by Tyler originally for the U.S. military. The device electrically stimulates the vagus nerve through the ear by way of headphones. Tyler has used similar devices to treat anxiety and sleep problems in people with autism spectrum disorder, help Department of Defense employees learn foreign languages more quickly, and enable a veteran with crippling PTSD to take part in a high-stakes putting tournament.

A transcranial auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) device designed by Tyler originally for the U.S. military. The device electrically stimulates the vagus nerve through the ear by way of headphones. Tyler has used similar devices to treat anxiety and sleep problems in people with autism spectrum disorder, help Department of Defense employees learn foreign languages more quickly, and enable a veteran with crippling PTSD to take part in a high-stakes putting tournament.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

The Apple Store of brain tech

But Tyler says the Alabama BRAIN Lab is interested in other types of technology as well. The lab looks like a cross between a doctor’s office and an Apple Store, with more of the latter’s vibe. One room has a standard physical therapist’s table. The next three contain a gleaming white transcranial magnetic ultrasound machine; a training station for elite athletes made by a startup spun off from Nike; a handheld device, applied to the neck, to treat headaches and depression; multi-colored LED light sculptures programmed to use frequencies that boost calm and focus; and a $26,000 machine that aims to recreate the sense of awe and wonder produced by psychedelic drugs through sounds, smells and ultra-fast, ultra-bright light patterns. Each of these machines has generated interesting data from small human studies. Tyler and his team want to see if they can help UAB patients — people recovering from cancer, strokes and spinal cord injuries, or dealing with chronic conditions such as multiple sclerosis. “Academic studies have 10 to 20 people total; at my startups, I would run that in a day,” Tyler said. “It’s a completely different scale. We want 200 people in our studies, so that patients don’t have to wait 17 years for a new therapy to reach the clinic.”

Another device being tested in the lab: the Lucia No. 3, a "hypnagogic" machine that purports to recreate the sense of awe and wonder produced by psychedelic drugs through ultra-fast, ultra-bright light patterns.

Another device being tested in the lab: the Lucia No. 3, a "hypnagogic" machine that purports to recreate the sense of awe and wonder produced by psychedelic drugs through ultra-fast, ultra-bright light patterns.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

Physical therapy + personalized neuromodulation

The manager of the Alabama BRAIN Lab is Alex Evancho, DPT, who holds a doctorate in physical therapy from UAB and is a research assistant professor in the School of Health Professions. “I believe the future is in combining neuromodulation with physical therapy,” Tyler said. “We know that movement-based physical therapy can enhance neuroplastic change,” Evancho added. “We want to enhance that neuroplasticity. We’re going to focus on movement-based therapies, pairing brain stimulation with exercise and looking at the timing relationships. If you put on a taVNS device for 15 minutes before your physical therapy, will that help?”

An emerging theory of physical therapy focuses on the neuroplastic effects in the brain. “We’re looking at a new model of physical therapy with personalized neuromodulation,” Evancho said. “Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation is very similar to what we as physical therapists already do with e-stim,” which uses mild electrical currents to help injured muscles heal.

A certain type of movement-based therapy called LSVT-BIG uses high-amplitude training to help patients overcome the slow movements (bradykinesia) seen in Parkinson’s, stroke, multiple sclerosis and other neurological conditions. “It has a good amount of evidence of effectiveness,” Evancho said. “How much better would it be if we added taVNS? Patients are often nervous and rigid. We could use taVNS to help them relax.”

Melissa Do demonstrates another taVNS device being tested in the BRAIN Lab. taVNS is already FDA-approved for treatment of depression and headache.

Melissa Do demonstrates another taVNS device being tested in the BRAIN Lab. taVNS is already FDA-approved for treatment of depression and headache.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

“A huge impact”

Tyler, Evancho and another lab member, Wendy Reed, Ph.D., MPH, have been meeting with patient advocacy groups around the state to explain their work and find out more about the groups’ needs and concerns. “We asked, ‘What are you looking for?’” Tyler said. “Everyone wanted a relationship with an entity that was conducting research and development and to participate in use.”

Tyler has worked closely with the Combat Wounded Veteran Challenge, a veterans’ service organization. “I’ve got some students who have started developing adaptive buoyancy devices and propulsion vehicles,” Tyler said. “We also have collaborations with people who build prosthetics to work with them to build adaptive devices.” The Lakeshore Foundation, a Birmingham-based nonprofit that provides world-class rehabilitation for people with disabling conditions, works closely with UAB’s School of Health Professions. “Lakeshore is one of the things that drew me here,” Tyler said. “You can make such a huge impact.”

Reed, the lab's director of communications and engagement, completed her master's degree in public health this spring; she is interested in using light therapies to help patients with traumatic brain injury. Another member of the Alabama BRAIN Lab team is Keith McGregor, Ph.D., associate professor and research director in the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences in the School of Health Professions. McGregor studies how cognition, strength and control of movement decline with age and how lifestyle interventions such as exercise can slow that decline. On a recent visit to the Alabama BRAIN Lab, McGregor and a student were setting up a transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, device in one room. These machines are FDA-approved for treating depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and headache pain. McGregor uses TMS and other technologies to study brain function.

Tyler and McGregor are principal investigator and co-principal investigator, respectively, on a new National Science Foundation project that aims to map circuits deep in the brain that underlie human cognition, emotion and decision-making. The work, funded by a three-year, $1 million grant, includes collaborators at Auburn University (Meredith Reid, Ph.D.) and Arizona State University (Chris Blais, Ph.D.).

Students are eager to get involved in these projects, Tyler notes. “I’m teaching a course on Advanced Clinical Innovation,” he said. “Two students came up to me and said, ‘We saw the list of projects for the Alabama BRAIN Lab. How can we be a part of it?’”