In fiscal year 2019, UAB researchers received a record $602 million in grants and contracts, marking a second year of double-digit percentage growth in funding. That productivity has carried on unabated in 2020, and you can follow along. Every Tuesday, Research Administration releases a list of the grants and contracts awarded the previous week (BlazerID required).

In this new series, we’re spotlighting new or re-funded projects to offer a window into the groundbreaking, lifesaving work done by our colleagues around campus. (See other stories in this series, profiling grants to derive equations against breast cancer, study back pain, accelerate HIV suppression, test a new strategy against lupus, stop online opioid sales and build freezers for the International Space Station.)

This week, we’re taking a look at a project that is testing a UAB-developed algorithm to help busy providers navigate the complex world of smoking-cessation treatments.

Project title: Effectiveness of a Smoking Cessation Algorithm Integrated into HIV Primary Care

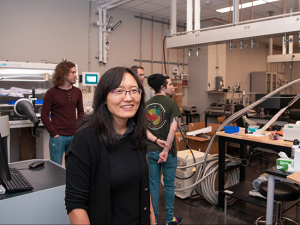

Principal investigator: Karen Cropsey, PsyD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology; investigator: Ellen Eaton, M.D., Department of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases

Funding: Five years, $3.4 million from the National Institute on Drug Abuse

Advances in treatments for HIV/AIDS have raised life expectancy for patients dramatically. But one of the results of that success, paradoxically, is to increase the risk for tobacco-related illnesses and death in this group. People living with HIV and AIDS are more likely to smoke than the general population. But research has shown that the health care providers who offer primary care to these patients don’t usually bring up the topic of smoking-cessation. “The problem is most providers have never been trained how to do it,” said Karen Cropsey, PsyD, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology in the School of Medicine and co-director of the school’s new Center for Addiction and Pain Prevention and Intervention.

Advances in treatments for HIV/AIDS have raised life expectancy for patients dramatically. But one of the results of that success, paradoxically, is to increase the risk for tobacco-related illnesses and death in this group. People living with HIV and AIDS are more likely to smoke than the general population. But research has shown that the health care providers who offer primary care to these patients don’t usually bring up the topic of smoking-cessation. “The problem is most providers have never been trained how to do it,” said Karen Cropsey, PsyD, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology in the School of Medicine and co-director of the school’s new Center for Addiction and Pain Prevention and Intervention.

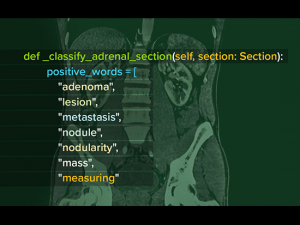

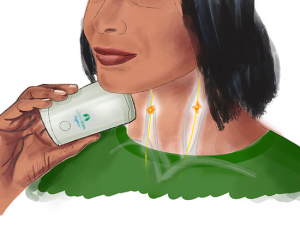

The sheer number of options to recommend also can be daunting. “Smoking-cessation has seven first-line pharmacotherapies,” Cropsey said. There are the nicotine replacements — patches, gum, lozenges, inhalers and nasal sprays — and the medications buproprion (Zyban) and varenicline (Chantix).

In a preliminary study in HIV clinics at UAB and the Medical University of South Carolina, Cropsey and colleagues tested the idea of using an algorithm to help providers know when to offer therapies and, critically, which are best for various types of patients. The success of that study led to a five-year, $3.4 million R01 grant from the NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, with Cropsey as the principal investigator. The grant, titled Effectiveness of a Smoking Cessation Algorithm Integrated Into HIV Primary Care, will test the intervention on a wider scale at three clinics nationwide.

“The idea is to give providers the tools to be able to help patients quit smoking without having to do lengthy, in-depth training that they just don’t have time for,” Cropsey said. “This standardizes quitting smoking as something with clear guidance. If you can get patients to answer just a few questions — Do you want to try to stop?, Have you tried quitting in the past? — it can give the provider a specific recommendation at the end.”

| “This standardizes quitting smoking as something with clear guidance. If you can get patients to answer just a few questions… it can give the provider a specific recommendation at the end.” |

If a patient wants to quit smoking and is willing to take a regular medication, for example, the algorithm recommends varenicline. If they have contraindications to varenicline, it recommends buproprion. “And if they don’t want to quit, that brings them to nicotine-replacement therapies such as the patch or gum,” Cropsey said. “The idea is that even people who are unwilling to try to quit can be offered pharmacotherapy.”

Cropsey developed the algorithm based on best clinical practice guidelines “and it can be tweaked as new clinical information becomes available,” she said.

UAB is the lead clinic for the R01 grant, with other sites in Boston at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Fenway clinic and at the University of Washington. “We’re hoping to test this algorithm in other locations and settings as well,” Cropsey added. Pre-operative waiting areas are one example. “Lots of surgeons want their patients to quit” but similar to HIV physicians they lack training or time for in-depth discussions, she noted. “This doesn’t require a lot of decision-making on the provider’s part. We feel that the algorithm approach can be applied more broadly.”