A study of ice and fire: Research by UAB nutritional epidemiologist Suzanne Judd, Ph.D., and colleagues, identified 19 foods and four lifestyle elements that raise or lower inflammation. See the big inflammation boosters, and effective ways to lower inflammation, in the box below.Hot sauce may burn the tongue, but the inner fire of inflammation brings real damage.

A study of ice and fire: Research by UAB nutritional epidemiologist Suzanne Judd, Ph.D., and colleagues, identified 19 foods and four lifestyle elements that raise or lower inflammation. See the big inflammation boosters, and effective ways to lower inflammation, in the box below.Hot sauce may burn the tongue, but the inner fire of inflammation brings real damage.

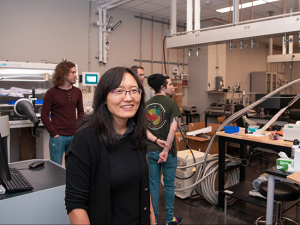

“We know inflammation is detrimental for heart disease, cancer and other chronic conditions,” said Suzanne Judd, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Biostatistics. Research has demonstrated that diet and lifestyle choices contribute to inflammation. But which foods and choices do we mean, exactly?

That is the sort of question that Judd, a nutritional epidemiologist, loves to tackle. In a new study, she and colleagues at Emory University provide answers in intriguing detail.

Using data from the massive, nationwide REGARDS study led by UAB, they compiled detailed records of food choices and lifestyle characteristics from a subset of 639 participants. Then they compared these records with the same participants’ inflammatory status — as measured by blood levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukins 6, 8 and 10 — and calculated the strengths of association between the inflammatory markers and individual food choices and lifestyle activities. That allowed the investigators to determine specific weights for each of 19 foods and four lifestyle elements. Foods or activities with negative numbers lowered inflammation; those with positive numbers increased inflammation. (See “Fire and ice.”)

By adding up all the weights for a person’s diet and lifestyle, the researchers created two new scores: a dietary inflammation score (DIS) and a lifestyle inflammation score (LIS). The scores were validated in more than 14,200 additional REGARDS participants. “Higher dietary and lifestyle inflammation scores of all types were generally strongly, positively associated with inflammation biomarkers,” the investigators wrote in the December 2019 print issue of the Journal of Nutrition.

"Rather than looking at nutrients, we wanted to look more upstream at diet and lifestyle outcomes, to better understand how they are mingled," Judd said.Two existing scoring systems, the DII and EDIP, focus on specific nutrients, rather than whole foods, Judd explained. And there is no current scoring system to gauge the effect of lifestyle on inflammation. “We wanted to create new scores that are a proxy for inflammatory status,” Judd said. “Rather than looking at nutrients, we wanted to look more upstream at diet and lifestyle outcomes, to better understand how they are mingled.” The results support the contention that “diet and lifestyle both contribute substantially [to systemic inflammation] — lifestyle more than diet — but especially in interaction with one another,” the authors wrote.

"Rather than looking at nutrients, we wanted to look more upstream at diet and lifestyle outcomes, to better understand how they are mingled," Judd said.Two existing scoring systems, the DII and EDIP, focus on specific nutrients, rather than whole foods, Judd explained. And there is no current scoring system to gauge the effect of lifestyle on inflammation. “We wanted to create new scores that are a proxy for inflammatory status,” Judd said. “Rather than looking at nutrients, we wanted to look more upstream at diet and lifestyle outcomes, to better understand how they are mingled.” The results support the contention that “diet and lifestyle both contribute substantially [to systemic inflammation] — lifestyle more than diet — but especially in interaction with one another,” the authors wrote.

“We’ve done a lot of work to explore participants’ diet in REGARDS, because it provides a unique opportunity to examine diet from the population perspective,” said Judd, who is a co-principal investigator for that study. REGARDS, which began in 2003, was designed to learn why more African Americans die from strokes than other races, and why people in the Southeast have a higher stroke risk than people in the rest of the country. It has enrolled more than 30,000 black and white people ages 45 and older, living in 1,866 counties across the United States.

“Usually you get homogenous diet patterns in studies,” because participants come from the same region or ethnic background, Judd said. But because REGARDS has enrolled participants from across the country, and is racially heterogenous (nearly half of participants are African American), it is able to overcome these obstacles.

The next step for the DIS and LIS? Using them as epidemiological tools for future studies examining the “collective contributions of dietary and lifestyle exposures to systemic inflammation,” Judd and her co-authors write.

In addition to Judd, authors of Development and Validation of Novel Dietary and Lifestyle Inflammation Scores were Doratha Byrd, Ph.D., W. Dana Flanders, M.D., DSc, Terryl Hartman, Ph.D., Veronika Fedirko, Ph.D., and Roberd Bostick, M.D. of Emory University.

Poultry: –0.45

Poultry: –0.45 Processed meats: +0.68

Processed meats: +0.68  Moderate drinking (1 drink/day for women, 1–2 drinks/day for men): –0.66

Moderate drinking (1 drink/day for women, 1–2 drinks/day for men): –0.66 Heavy physical activity: –0.41

Heavy physical activity: –0.41 Current smoker: +0.50

Current smoker: +0.50