“When people are afraid to speak up, bad things happen," said Anthony Hood, Ph.D., who studies team dynamics in the Collat School of Business. Psychological safety, a shared belief that a team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking, empowers workers and enhances the bottom line, Hood noted.Think back to your last meeting — was it safe? Not physically, mind you, but emotionally, psychologically.

“When people are afraid to speak up, bad things happen," said Anthony Hood, Ph.D., who studies team dynamics in the Collat School of Business. Psychological safety, a shared belief that a team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking, empowers workers and enhances the bottom line, Hood noted.Think back to your last meeting — was it safe? Not physically, mind you, but emotionally, psychologically.

How about your work team? Consider these questions:

- If you make a mistake on your team, is it held against you?

- Are you able to bring up problems and tough issues?

- Do people on the team sometimes reject others for being different?

- Is it safe to take a risk?

- Is it difficult to ask other team members for help?

- Do people on the team deliberately act to undermine your efforts?

- Are your unique skills and talents valued and utilized?

In a landmark 1999 study, Harvard researcher Amy Edmondson, Ph.D., used a similar set of questions to measure something she called team psychological safety — “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking,” as she wrote in the introduction to her paper.

Welcome to the jungle

Whether you think of your workplace as a jungle or a second home, your work life is all about estimating risk. “Humans are hard-wired to recognize threats and govern ourselves accordingly,” said Anthony Hood, Ph.D., an associate professor of management in the UAB Collat School of Business whose research focuses on team dynamics. “We have a hyper-vigilance to threat. It’s our fight-or-flight response.”

We want to protect ourselves. So in every meeting, our feelers are out. Are people listening when I present ideas — or is my voice ignored? How does the boss react when she gets bad news? Does it feel like I can admit to my co-workers that I don’t know how to do something — or will they use that against me?

Are people listening when I present ideas — or is my voice ignored? How does the boss react when she gets bad news? Can I admit that I don’t know how to do something — or will my coworkers use that against me? |

The answers to these questions “make the difference between waking up every Monday morning excited to go to work or sick to your stomach that you have to spend yet another week working for and with those people,” Hood said. These answers also determine whether you are willing to take a risk to suggest a new way of doing things or a better process to get the job done in your office.

Psychological safety may sound like it means nothing more than good vibes, but it’s deadly serious. “Lack of psychological safety explains why airplanes run into the sides of mountains or patients get their right leg operated on when they came in for surgery on their left,” Hood said. “When people are afraid to speak up, bad things happen.”

Hood, who also is director of civic innovation in the Office of the President at UAB, leads workshops on building better teams that are popular all across campus, from academic departments and administrative units to research labs. He is sought after by businesses across Birmingham and around the region, including Alabama Power, Regions and Brasfield and Gorrie.

One psychological test used by Google's team-building researchers is known as Reading the Mind in the Eyes, which is used to measure social sensitivity. You can try out the test at this research site run by a team from the University of Washington. On a phone? The New York Times has a version you can take (that will give you instant feedback on answers, too!).

One psychological test used by Google's team-building researchers is known as Reading the Mind in the Eyes, which is used to measure social sensitivity. You can try out the test at this research site run by a team from the University of Washington. On a phone? The New York Times has a version you can take (that will give you instant feedback on answers, too!).

Psychological safety pays off

Psychological safety, Hood explains to those groups, helps the bottom line. In a multi-year effort known as Project Aristotle, Google studied the behaviors of its most successful teams. The top factor in a successful team wasn’t intelligence or creativity or whether members attended elite schools — it was how psychologically safe the team was.

"Researchers are finding that psychological safety may be the No. 1 aspect of successful teams, driving creativity and innovation.” |

“Researchers are finding that psychological safety may be the No. 1 aspect of successful teams, driving creativity and innovation,” Hood said. That’s because, as work becomes more complex and resources get tighter, team success depends on effective distribution of the workload. If teams can divide up their work to take maximum advantage of each member’s skills, they can get more done. But first, everyone has to admit they can’t do it all on their own. Team members have to engage in “potentially risky interpersonal behaviors, such as admitting information deficiencies, declaring expertise, justifying or defending expertise when challenged and admitting lack of desire to accept responsibility for a particular expertise domain,” as Hood and his co-authors explained in a 2015 study on psychological safety, published in the Journal of Organizational Behavior.

So how can managers encourage their employees to open up to risk? It’s not simply a matter of making everybody “think positive.” For that 2015 study, Hood and colleagues studied 668 information technology professionals assigned to 121 enterprise resource-planning software-implementation teams. Among the study’s key findings were that the extent to which a team’s environment is perceived to be psychologically safe is influenced by its members’ general disposition towards positivity (e.g. cheerful, energetic and optimistic) or negativity (e.g. fear, anxiety, and anger). That has implications for supervisors in industries where the composition of their project teams are in a constant state of flux. But what if you’ve got a set team and want to make it safer?

"To build psychological safety you have to be willing to be vulnerable first, to show your employees that it is OK," Hood said.

"To build psychological safety you have to be willing to be vulnerable first, to show your employees that it is OK," Hood said.

Managers: How to get safe

Psychological safety is usually set from the top down, Hood said. When he presents to leaders — as he did at the Leadership Edge for New Managers training at UAB this spring — Hood shares several ways to make that happen.

1. Everybody makes mistakes — even me

“If you are unable or unwilling to be psychologically and emotionally vulnerable with your team, then there’s a good chance your people don’t feel psychologically safe with you,” Hood said. “Sometimes managers are resistant because they feel like the process makes them look weak, that people will walk all over them. But to build psychological safety you have to be willing to be vulnerable first, to show your employees that it is OK. You need to admit when you’ve made a mistake and show that you are human, too. It is critical to create an environment where experimentation and learning from failure is celebrated rather than punished.”

Related story:Get advice from new leaders on what works for them in How to get ahead at UAB: improve others, improve yourself — including the rounding form that nurse managers use to check in with their staffs.“Rounding is a wonderful tool,” said Bronwyn McInturff, who manages a team of fellow counselors in the UAB Addiction Recovery Program. “It invites people to share and tell me things that are helpful to me as a manager and also points out threats I might not be aware of." |

2. Watch your reactions

“Leaders need to be very mindful of how they react to mistakes,” Hood said. “If you fly off the handle when your team brings you a problem you send a message that failure and experimentation are not acceptable. And when people get that message they hide their errors.”

3. Listen as much as you speak

“Have an open-door policy,” Hood said. “Make sure you have a regular time where people can come and talk to you. And if you are in a more senior role, create skip-level meetings, in which front-line employees can talk to you directly about what they are experiencing without their immediate supervisor present.”

4. Encourage people to ask for help

“If employees ask for help and are subsequently treated as if they are incompetent or slackers, they’ll suffer in silence, but the workplace will suffer as well,” Hood said.

“Don’t wait for them to come to you, either,” he added. “Go ask them, do you need help? Are you good? Give them the benefit of the doubt.”

5. Clarity for everyone

Psychological safety is particularly important when teams work in situations that are literally life-and-death, such as health care and aviation, Hood said. The National Institutes of Health has developed Team STEPPS, a “team-based training platform” that focuses on a culture of safety, Hood said, including “making clear the roles and responsibilities with a pre-briefing beforehand and a debriefing afterward.”

6. Speak of the devil

In the business world, “some teams will assign a person to play devil’s advocate,” Hood said. “They say, ‘We don’t want to be prone to groupthink, so it’s your job to come up with the counterpoint to every decision we make or to think about how this could go wrong.’ Ensuring there will be some intellectual friction boosts creativity and innovation by expanding the range of ideas and solutions available for complex decision-making and problem-solving.”

"If you fly off the handle when your team brings you a problem you send a message that failure and experimentation are not acceptable," Hood said. "And when people get that message they hide their errors."

"If you fly off the handle when your team brings you a problem you send a message that failure and experimentation are not acceptable," Hood said. "And when people get that message they hide their errors."

Employees: How to get safe

If you are an employee in a psychologically unsafe environment, realize that you always have options, Hood said.

1. Plan ahead

“The importance of ‘managing up’ cannot be overstated, especially if your manager has a reputation for being difficult or passive-aggressive,” Hood said. “It takes some political savvy when you are trying to drive change across levels of power, but it can be done. To start off, monitor the personality and moods of your leader and how they respond best to difficult conversations. Leaders are people, too — and sometimes they are dealt a bad hand by those above them. Other times they may be dealing with personal issues outside the workplace. Empathize with them and the unfortunate situations they may be facing.

Build your case using the organization's structure and explicitly stated strategies. At UAB, think of the UAB Shared Values — such as collaboration — and Forging the Future, UAB's strategic plan.

Build your case using the organization's structure and explicitly stated strategies. At UAB, think of the UAB Shared Values — such as collaboration — and Forging the Future, UAB's strategic plan.

2. Strictly business

“Never make it personal,” Hood said. He always builds his case using the organization’s structure and explicitly stated strategies. [At UAB, think of the UAB Shared Values and Forging the Future, UAB’s strategic plan. Collaboration — trusting each other and working cooperatively — is one of the seven Shared Values.]

“Also, draw on the manager’s own words,” Hood said. “You might say, ‘You’ve always told us we should’ — fill in the blank — ‘and to that end I recommend we…’ Focus on proposing solutions, rather than restating the obvious problems and constraints.’

3. Realize you may need to move on

“Working in a psychologically unsafe environment can be detrimental to your mental health and emotional well-being,” Hood said. A new $1.8 million grant from the American Medical Association to UAB and three other leading academic medical centers will study emotional exhaustion, depression and burnout among physicians, he points out — just one example of rising burnout in health care settings and other workplaces.

“If your supervisor or the organization still doesn’t get it, it may just be a bad fit,” Hood said. “Please know that you always have options. There is a shortage of talent everywhere. Make the courageous decision to seek opportunities elsewhere in the organization or the industry.” That can be difficult, especially when you’re in a successful situation professionally, he said. “No one should be made to choose between their well-being and their career.”

Safety never sleeps

Whether you are a leader or a team member, everyone can help to create psychological safety, Hood added. “When I’m scanning the room at a meeting I can often see when people are feeling unsafe,” he said. “A person had the courage to speak up and no one responded to what they said, for example. When I see that, I try to jump in and say to that person, ‘Can you go back to what you were saying?’ Ensuring that our teammates’ voices are heard and their ideas are respected is the responsibility of all team members. That’s the process of creating safety.”

And the process never stops. Psychological safety isn’t something you can create and then move on, Hood said. “It can ebb and flow on a weekly basis. Trust can be destroyed in one act. It requires us all to be thoughtful and vigilant. The best way is to be proactive about it. If you give safety you’ll get safety in return.”

Too safe?

That said, there are times when some members of a team may be too safe, Hood said. “Consider for instance the phenomenon in the startup environment commonly known as ‘bro culture.’ This environment can emerge when the founding team exclusively comprises men — particularly those from one racial or ethnic background. Such environments may encourage racially insensitive jokes, sexually suggestive banter, workaholism, binge drinking and offensive office decor. Customs formed among the early founding team may be safe to them, but toxic and offensive to women and racial/ethnic minorities subsequently added to the team,” he said. This is something Hood discusses with startup founders as an entrepreneur-in-residence for the Velocity Accelerator program in Birmingham’s Innovation Depot, where he is a mentor for the 2019 cohort.

“Psychological safety is a particularly tough challenge in small teams, especially when you’re in business with a best friend, parent, kid or spouse,” Hood said. “Sometimes if you’re too close to people they take liberties with the relationship — forcing you have to manage both roles at the same time.” These multiplex relationships, as Hood calls them, were the subject of a 2017 study he led that resulted in the paper “Conflicts with Friends,” which was named one of the top papers of the year by the Journal of Business and Psychology.

“That’s where my research is taking me next,” Hood said. “I’m thinking more about the dark sides of psychological safety — when one person’s safety makes another unsafe.”

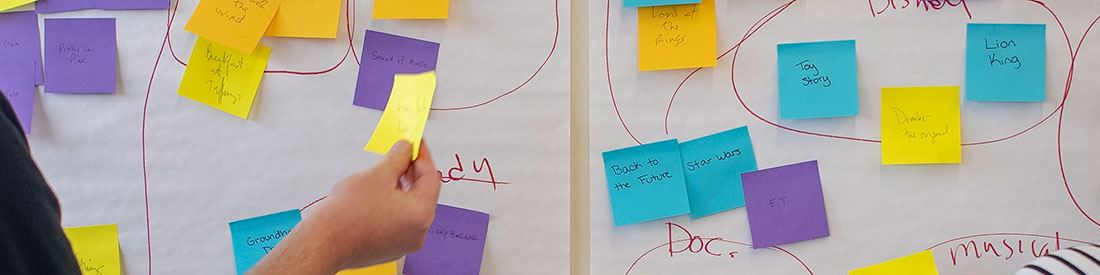

A ‘prenup’ for team-based learning

“They’ll come in and say, ‘Dr. Hood, we need to fire Matt from the team. He’s not pulling his weight.’ And I’ll ask them to tell me about Matt‘s response when they informed him of their grievances. And they say, ‘Well, we haven’t actually talked to him about it. He should just know.’” The issue came up frequently enough that Hood now takes his students through a version of the popular team-building workshop he gives to corporate clients. “I’ve realized the value of doing this workshop the first week of class,” he said. That includes having each of his student teams create a team charter before they begin. “It’s like a prenuptial agreement for teams,” Hood said. It lists the names of the participants, their class and work schedules, and each member’s strengths and weaknesses. “That’s a great way to head off potential conflicts,” Hood said. “Have an honest conversation up front.” That includes creating “a grievance policy, with clear consequences and remedies for non-performance,” he said. “I’ve been doing it for the last couple of years now, and it has reduced the number of student-grievance meetings tremendously.” The contract template that Hood uses was inspired by calls from the National Institutes of Health. For the past several years, the NIH has been advocating that grant-funded teams develop collaboration plans to head off the infighting and division-of-credit squabbles that can sabotage scientific collaborations. Hood, who was previously the lead trainer for team science with UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, has been teaching workshops on developing collaboration plans. “In my opinion, including something like that in your grant proposal will give you a competitive edge,” he said. |

For the past several years, faculty throughout UAB have focused on team-building as part of the university’s Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP),

For the past several years, faculty throughout UAB have focused on team-building as part of the university’s Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP),