“People think, ‘Either I treat people well or I achieve my objectives,’” said David A. Rogers, M.D., UAB Medicine’s chief wellness officer. “In the short term that feels right; but in the long term, the winning strategy is to do both."There is an unusual book making the rounds at UAB. The chapters are short and grounded in scholarship but also in humanity and practical advice. Like a Dickens novel or a modern sneaker drop, it is being released in serial form, with two chapters currently circulating of 10 total, and fresh chapters published every quarter. At least, that was the original idea. But the response has been so strong, and the need so great, that this cadence has been accelerated. A full print version is coming — just as soon as the authors finish writing it.

“People think, ‘Either I treat people well or I achieve my objectives,’” said David A. Rogers, M.D., UAB Medicine’s chief wellness officer. “In the short term that feels right; but in the long term, the winning strategy is to do both."There is an unusual book making the rounds at UAB. The chapters are short and grounded in scholarship but also in humanity and practical advice. Like a Dickens novel or a modern sneaker drop, it is being released in serial form, with two chapters currently circulating of 10 total, and fresh chapters published every quarter. At least, that was the original idea. But the response has been so strong, and the need so great, that this cadence has been accelerated. A full print version is coming — just as soon as the authors finish writing it.

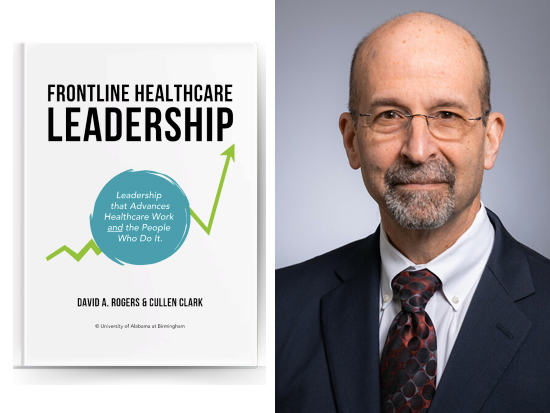

“Frontline Healthcare Leadership,” by David Rogers, M.D., and Cullen Clark, Ph.D., is a leadership book whose target audience has no time for reading leadership books. As the subtitle explains, its mission is to build “leadership that advances healthcare work and the people who do it.” In this writer’s opinion, it has valuable insights that can help you contribute to making UAB an even better place to work, be healed and learn, whether you are a manager or not, and no matter where you work on campus, from the medical center to the Hill Student Center.

Can you treat people well and achieve objectives?

“People think, ‘Either I treat people well or I achieve my objectives,’” said Rogers, UAB Medicine’s chief wellness officer and a pediatric surgeon by training. “In the short term that feels right; but in the long term, the winning strategy is to do both. By treating people well and helping in their development, that is how you will achieve your objectives most directly. And if I can help you as a leader be better, I can help the people that work for you as well.”

Rogers is the co-director of the UAB Healthcare Leadership Academy, one of the institution’s premier leadership programs and a collaboration between the Collat School of Business and Heersink School of Medicine. Many of the employees in those programs have spent years training to manage teams, or are able to devote nine months to enhancing their skills. “Frontline Healthcare Leadership” was written for people who do not have that time: nurse managers and team leaders of EKG technicians, respiratory therapists, and the other specialists who power the modern health care system.

"On Monday, you're in charge"

In those positions, “you start out with technical training or a bachelor’s degree that was designed to equip you for your patient care role, and if you are good, you pretty quickly move into some kind of leadership role,” Rogers said. “All of a sudden, you have these responsibilities and no formal training. Your boss comes to you and says, ‘We’ve had someone leave. On Monday, you are in charge of the group.’ For a long time, I’ve felt like what we do in academic medicine would be better if we were doing more to equip these leaders and at least get them information quickly.”

That is what this project is about, Rogers explained: “The idea is someone can say, ‘Here’s a book you can read in a weekend and help you get up to speed.’” Or, as Rogers describes it in the introduction, “My hope for this book is to be a lifeline for frontline healthcare leaders who find themselves thrust into leadership roles without formal preparation or resources.”

Helping these workers can have a widespread effect on the medical center, Rogers says. Studies, including by Katherine Meese, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Health Services Administration and director of Research in the Office of Wellness, show that “the immediate leader is quite impactful on most employees,” Rogers said. “We have to help make those people be successful.”

Practical advice tuned to UAB's culture

The lessons in “Frontline Healthcare Leadership” are widely applicable. For instance, have you thought much about what makes a good job? In his second chapter, Rogers discusses various models of optimal work. Money is a motivating factor, of course. But according to an influential, research-backed framework called Self-Determination Theory, three features of work are most important to the majority of people: autonomy, competence and related. “Any job requires balancing the demands of the work and the resources available,” Rogers said. “Do you have enough resources that you are capable of doing your work? Can you be creative? Do you have people at work that care about you as a person?”

Practical advice tuned to UAB’s culture abounds. Do you want to know how a UAB colleague has used small changes in the agendas of her meetings to reduce groupthink? And how such “microadjustments” can set the foundation for a positive workplace culture in your office or workspace? Read how a young professor has implemented these steps with her team. How can you design new positions with the goal of creating optimal work? See chapter 2. In that chapter you also will learn what post-pandemic studies have to say about the importance of autonomy in any job. Need advice on implementing job crafting? That is coming up in Chapter Four.

Perhaps most of all, “Frontline Healthcare Leadership” acts as a guide to thinking about your own work experience and the ways in which organizational hierarchies shape the meaning of everyday work interactions. In Chapter 3, Rogers quotes the “surprisingly sociological conclusion” of a biblical scholar’s commentary on King David’s disastrous census: “To those who have power, bureaucratic processes most often seem benign, necessary or neutral. But to those who live their lives outside the circles of power … such processes are threatening and dangerous.”

Understand the social forces shaping modern work

Each chapter concludes with comments from Clark on the sociological issues raised. Reflecting on the third chapter’s summary of “threats to optimal work,” from Taylorism to McDonaldization, Clark shares an evocative phrase from sociologist Zygmunt Bauman: “liquid modernity.” “Contemporary life, including work, seems fragile, uncertain, constantly changing and marred by a lack of stable relationships,“ Clark writes. “Anyone who has worked in healthcare intuitively understands what Bauman is describing. From the introduction of diagnosis-related groups to the arrival of COVID, the last 40 years have been an era of uncertainty, anxiety and constant change in healthcare.” Understanding the social forces shaping modern work “can provide context and help leaders better navigate the system as they try to ensure optimal work that benefits patients and co-workers alike.”

Rogers, who came to UAB in 2012 as senior associate dean for Faculty Development in the School of Medicine, became the nation’s first endowed chair for physician wellness in 2017 thanks to a $1.5 million gift from Birmingham-based ProAssurance Corporation and was named UAB Medicine’s chief wellness officer in 2018. His work took on new urgency post-pandemic, when UAB, along with other institutions nationwide, was confronted with unprecedented staffing shortages, retention issues and employee wellness concerns. In 2022, Rogers talked with a colleague in the medical center who was taking advantage of the university’s Educational Assistance benefit to go back to school. “I had always been interested in groups and team dynamics and had done some research on teams,” Rogers said. “I discovered UAB’s master’s program in sociology and saw that it had a good reputation and was fully online, so I signed up.”

Rogers says he was particularly impressed with the classes he took with Clark, a specialist in applied sociology and director of the online master’s program. Clark has an atypical background for an academic: He was a journalist and senior leader at health systems in Ohio and Alabama for decades before returning to graduate school to complete his doctorate in medical sociology.

“Each course involved writing a paper where you apply the concepts you are learning to your work,” Rogers said. “The founding sociologists were writing during the Industrial Revolution; they were interested in what these changes in the Industrial Revolution were doing to the workforce and society in general. It is shocking how relevant their work is to what we are dealing with now.”

An unorthodox strategy

For his final project, Rogers submitted a book proposal to a publisher. The publisher suggested another company that could be a better fit; instead, Rogers decided to adopt his unorthodox distribution strategy.

He asked Clark to join him as a co-author “to keep me straight on the sociology” and to write a commentary at the end of each chapter that reflects on the theories and leadership applications that Rogers covered.

Rogers also notes the contributions of Nisha Patel, then-administrative director of the Office of Wellness, and Valerie Minor, the editor of Take 5, the Office of Wellness e-newsletter, who have created infographics to summarize the key points of each chapter. “I thought that was important,” Rogers said. “Somebody gives you this book and you can flip through it in a weekend. The infographics give you a summary of the chapter so you can remember.”

The plan was to share chapters quarterly in Take 5. But the response has been strong enough, and the needs Rogers hears from frontline workers are so great, that he is accelerating his timeline. He hopes to have a print version ready in spring 2025. “This is really a love letter to UAB,” he said. “There are things we do that, as chief wellness officer, I know help. We can’t get to all 30,000 people at UAB; but if we can focus on leadership that promotes people, we can move toward that goal.”