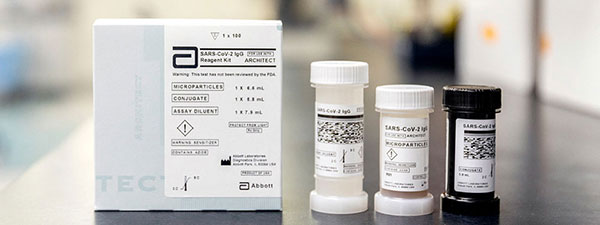

UAB is using the Architect antibody test from Abbott. Image courtesy Abbott.Have I had COVID-19?

UAB is using the Architect antibody test from Abbott. Image courtesy Abbott.Have I had COVID-19?

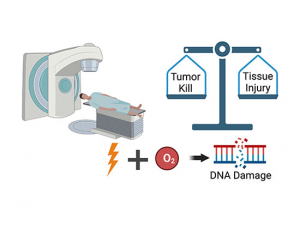

That is one of the biggest questions in the world right now, and many people are looking to COVID-19 antibody tests for the answer. These blood tests search for the presence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The tests expose a person’s blood to (inactive) pieces of SARS-CoV-2. Antibodies are highly specific; if a person’s blood contains antibodies that bind to SARS-CoV-2, that person has probably been infected sometime in the past two weeks to several months.

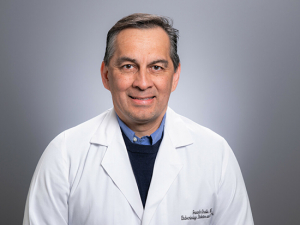

There are a number of different antibody tests available, of varying reliability. The test currently used at UAB, by Abbott, has proven to be accurate, said Jose Lima, M.D., director of the UAB Immunology Lab in the Department of Pathology, which can run hundreds of antibody tests per day. The Abbott test looks for the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that are reactive against SARS-CoV-2. IgG antibodies are produced in the second wave of the body’s response against infection and are more long-lasting than their precursor antibodies, immunoglobulin M (IgM).

Not information you can act on — yet

“There are people who were sick in March or April [or earlier in the year], and they feel it will give them peace of mind to know whether they had COVID-19,” said Jodie Dionne-Odom, M.D., assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases. “That makes sense. I would be interested in knowing my results on an antibody test as well. But you don’t want to give yourself false hope — antibody tests are not giving you information you can act on yet.”

That’s not because testing is inherently inaccurate.

“There are people who were sick in March or April and they feel it will give them peace of mind to know whether they had COVID-19. That makes sense. I would be interested in knowing my results on an antibody test as well. But you don’t want to give yourself false hope — antibody tests are not giving you information you can act on yet.” |

“We are happy with the test that we have,” Lima said. “We have not seen a lot of either false positives [identifying someone as having been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, even when they have not] or false negatives [failing to identify someone who has been exposed].” His lab has been comparing its antibody test results with samples from the same patients who received positive results with the PCR tests used to diagnose active COVID-19 infection. They match closely, Lima said.

So what do antibody tests tell you?

“That’s probably the only question that we can answer so far with that test specifically,” Lima said. “If a person has had contact with the virus recently, it will tell you.”

Timing is important. “It takes 14- to 21 days to develop a good IgG response,” Dionne-Odom said. “If you get the test too early after exposure, antibody levels may not be high enough to produce a positive test.”

If taken during the right timeframe, though, a positive antibody test — also referred to as a reactive antibody test — means you likely have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. A negative antibody test, or nonreactive antibody test, means you likely have not been exposed.

Story continues after box

What does a positive result really mean?

But it is the next step that causes problems. “It is really important for people to understand what the result means for them,” Dionne-Odom said.

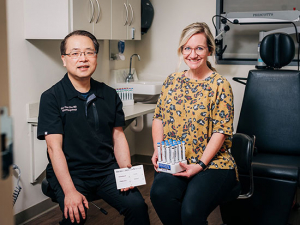

Jodie Dionne-Odom, M.D.People say, “I really want to know if I have been exposed so I can be with my granddaughter,” for instance. “But a positive antibody test doesn’t mean you can go out freely and not wear a mask,” Dionne-Odom said. We don’t have enough information yet to know if people with positive antibody tests are protected against another COVID-19 infection, or if they are capable of being carriers of COVID-19 and infecting others.

Jodie Dionne-Odom, M.D.People say, “I really want to know if I have been exposed so I can be with my granddaughter,” for instance. “But a positive antibody test doesn’t mean you can go out freely and not wear a mask,” Dionne-Odom said. We don’t have enough information yet to know if people with positive antibody tests are protected against another COVID-19 infection, or if they are capable of being carriers of COVID-19 and infecting others.

Dionne-Odom offers examples from other infectious diseases. “The immune response to infection is complex and antibodies are just one part of our armamentarium,” she said. In chronic infections like HIV, the presence of antibodies is not correlated with protection. “Having antibodies against HIV doesn’t clear the HIV,” she said. “It just means your body has seen the virus, not that you are protected the next time it encounters that virus.” Scientists are just beginning to understand which parts of the immune response are necessary to have protection against COVID-19. They are using this critical information to help develop an effective vaccine.

Dionne-Odom notes that questions remain about people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19: Do they develop antibodies? And, when antibodies develop, how long do they last?

It is important to draw a distinction between antibody tests and PCR tests, which are used to diagnose people with active COVID-19 infections. PCR tests look for the genetic material of the virus in a patient sample and are extremely precise.

“With antibody testing, you are no longer measuring the virus, but the body’s response to the virus,” Dionne-Odom said.

Who should consider antibody testing?

Any UAB physician can refer a patient for antibody testing, Lima noted. Good candidates for antibody testing include patients who have signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and are suspected to have the disease but may have had negative viral RNA testing.

Antibody testing will not detect an ongoing COVID-19 infection. If you have symptoms of COVID-19, you need to be diagnosed through PCR testing.

One of the best uses for antibody testing is to conduct epidemiological studies to gather data on the prevalence of COVID-19 in a community or region. And, once a correlation between antibodies and protection has been identified, antibody testing can be used to verify vaccine response.

Another major reason for antibody testing is to find good candidates for convalescent plasma therapy. (See below.) Because of this, both LifeSouth and the American Red Cross are testing all donated blood for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Both organizations will share the results of this testing with donors.

New antibody tests coming

Jose Lima, M.D.New antibody tests are on the horizon, Lima said, that focus specifically on the presence of antibodies that can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 — preventing it from slipping inside cells and damaging the body. “We have been evaluating several tests that are directly correlated with these neutralizing antibodies,” Lima said. These tests, which may be available at UAB within a few weeks, would be especially useful for identifying patients who would be the best candidates for convalescent plasma donation.

Jose Lima, M.D.New antibody tests are on the horizon, Lima said, that focus specifically on the presence of antibodies that can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 — preventing it from slipping inside cells and damaging the body. “We have been evaluating several tests that are directly correlated with these neutralizing antibodies,” Lima said. These tests, which may be available at UAB within a few weeks, would be especially useful for identifying patients who would be the best candidates for convalescent plasma donation.

Transfusing blood plasma from people who have recovered from infection into ill patients to help them fight off that same infection has been effective in a number of diseases and preliminary evidence for convalescent plasma as a treatment for COVID-19 is promising. UAB has been taking part in a clinical trial of convalescent plasma therapy in hospitalized patients since early May. A new trial, begun in August through Johns Hopkins University, will study convalescent plasma therapy in outpatients and people at high-risk for contracting COVID-19. (See this related story on convalescent plasma therapy at UAB.)

The new tests being studied in Lima’s lab would help identify the best candidates to donate plasma for these trials.