by Emma Shepard

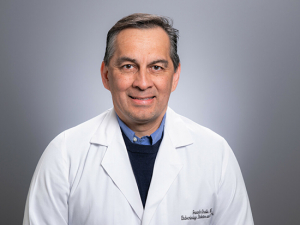

Ananda Basu, M.D., is director of the Diabetes Technology Program, professor in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, and a senior scientist in the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center.Diabetes is costly for both the American health care system and the estimated one in 10 Americans who have the disease. According to the American Diabetes Association, the costs in Alabama alone are some $5.9 billion each year.

Ananda Basu, M.D., is director of the Diabetes Technology Program, professor in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, and a senior scientist in the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center.Diabetes is costly for both the American health care system and the estimated one in 10 Americans who have the disease. According to the American Diabetes Association, the costs in Alabama alone are some $5.9 billion each year.

As the number of people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes continues to rise, clinicians and scientists are working together to find pragmatic, patient-centered solutions that could also lessen the formidable costs of managing this chronic disease.

Ananda Basu, M.D., is director of the Diabetes Technology Program and professor in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at UAB. He says proper diabetes care can reduce both outpatient clinic visits and emergency room visits, some of the most expensive interactions with the health care system.

“One of the major goals of diabetes care is to help patients manage their blood glucose so well that they never have to visit an emergency room for diabetic ketoacidosis, a deadly complication of diabetes,” said Basu, who is also a senior scientist in the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center. “We want our patients with diabetes to live a quality life without burning out on managing diabetes — and that is where diabetes technology comes in.”

Continuous glucose monitors and insulin pumps

Basu is particularly interested in two pieces of technology for diabetes management: the continuous glucose monitor and the insulin pump.

Using a sensor on the arm or abdomen, a continuous glucose monitor, or CGM, provides readings to those with diabetes at continuous intervals throughout the day. These readings can be in real time or on demand, whether the user chooses to get updates every five minutes or every few hours. A CGM sensor is usually changed every week or two weeks.

An insulin pump is attached to the body, normally on the arm, abdomen or near the hip, and can deliver insulin in a steady flow throughout the day, along with extra doses at mealtimes. It helps to alleviate the need for multiple insulin injections a day. Every two to three days, the user replaces the tube and refills the insulin cartridge, moving the insulin pump to a different location.

Most insulin pumps will deliver a small, continuous amount of insulin to the body throughout the day. This number is often set with the help of an endocrinologist, but some insulin-pump algorithms are able to predict the baseline dosage that a patient needs.

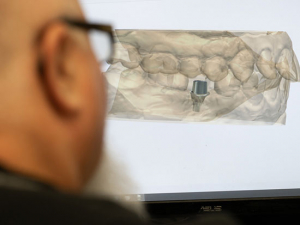

A sensor for a continuous glucose monitorThere are two types of CGM-insulin pump combinations. An open-loop system is patient-driven. They might see their blood sugar is high via the CGM and then instruct their insulin pump to deliver a certain amount of insulin. When the insulin pump is able to respond directly to the CGM reading without human intervention, this is a closed-loop system.

A sensor for a continuous glucose monitorThere are two types of CGM-insulin pump combinations. An open-loop system is patient-driven. They might see their blood sugar is high via the CGM and then instruct their insulin pump to deliver a certain amount of insulin. When the insulin pump is able to respond directly to the CGM reading without human intervention, this is a closed-loop system.

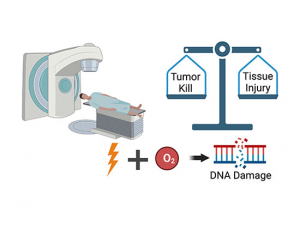

Closed-loop systems work by predicting where someone’s blood glucose might be within half an hour and sending signals, via Bluetooth, to the insulin pump to deliver insulin doses accordingly. Furthermore, these systems are constantly being upgraded to incorporate artificial intelligence, as well as adapt to changing circumstances (including signals from the CGM) in real time — much like a chess player adapting to changing moves by his/her opponent, Basu says.

Many scientists, engineers and diabetes professionals are working together, pushing to make the devices capable of predicting insulin needs even further out and making the algorithms better at keeping up with the sporadic choices of human behavior.

“The closed-loop system makes our patients feel as though they have an ‘artificial pancreas,’” Basu said. “The CGM and insulin pump work together to control blood glucose without the patient’s having to worry about it.”

Closing in on the artificial pancreas

For those with diabetes, today’s version of an artificial pancreas is a CGM and an insulin pump combined into a singular device that does both monitoring and insulin delivery. Several recent NIH-supported trials have shown benefits in patients with Type 1 diabetes from as young as a year old up to age 65.

“As the director of the Diabetes Technology Program, I often get asked by my patients when we will have an artificial pancreas,” Basu said. “The answer is that we already have several — three approved versions in the United States alone. But further research is ongoing to improve the algorithms contained within an artificial pancreas to make it completely automated while fitting to an individual patient with Type 1 diabetes.”

Dosing insulin using an insulin pump and remote sensorIn the future, Basu hopes these devices will more accurately mimic the human pancreas by incorporating all the other hormones the pancreas secretes — not just insulin. “This would be like giving the devices a full wheelhouse of tools to control blood glucose,” Basu said.

Dosing insulin using an insulin pump and remote sensorIn the future, Basu hopes these devices will more accurately mimic the human pancreas by incorporating all the other hormones the pancreas secretes — not just insulin. “This would be like giving the devices a full wheelhouse of tools to control blood glucose,” Basu said.

Diabetes professionals and engineers run into many challenges when creating one device for multiple hormones. Right now, artificial pancreases with both insulin (lowers blood glucose) and glucagon (raises blood glucose) have been tested in clinical trials. These devices have four attachment points to the body — two sensors and two needles for hormone delivery — so they can be bulky, Basu says.

Even when a true artificial pancreas makes its way to the market, adoption might be slow, Basu adds. Today many with diabetes have still not adopted the CGM and insulin pump technology, he points out.

Why are patients hesitant?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 37.3 million Americans — about one in 10 — have diabetes. However, only an estimated 350,000 people in the United States are using insulin pumps, and 2.4 million are using CGMs, Basu says.

Diabetes professionals largely agree that CGMs and insulin pumps work very well for managing diabetes and mitigating complications. So why do many people with diabetes still choose not to use a CGM and/or an insulin pump?

"I was ready to make a change and start managing my diabetes again and not let diabetes manage me. Switching to a CGM and insulin pump was the best decision I have ever made.” —Sarah Silverstein Mackintosh

“Many of my patients are hesitant,” Basu said. “But when I set them up on a trial basis, I have never had a patient want to return the pump and continuous glucose monitor. Everyone wants to keep the devices. It really is game-changing for those with diabetes.”

Basu does note that, for a lot of patients who manage their diabetes daily, having an artificial pancreas can feel as though they are losing a degree of control over their diabetes. Ultimately though, the research has shown that those with an insulin pump and CGM are able to spend more “percent time in range,” an observation that clinicians and scientists use to measure how often someone with diabetes is within an ideal blood glucose range.

“Those with diabetes who are interested in using a CGM or insulin pump should always consult with their endocrinologist and diabetes educator to learn more,” Basu said. “It is also important to understand what your health insurance provider covers when it comes to these devices.”

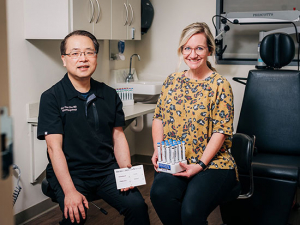

Sarah Silverstein Mackintosh, a Birmingham native and mother of two, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes as a young child. For her, making the switch to a CGM and insulin pump after decades of managing her diabetes on her own was difficult, she says.

But “after having my second baby, I realized that managing my diabetes was much more difficult with all the added responsibilities of being a mother,” Mackintosh said. “I was late taking my medicine and forgetting to check my blood sugars. I was ready to make a change and start managing my diabetes again and not let diabetes manage me. Switching to a CGM and insulin pump was the best decision I have ever made.”

Ultimately, for Mackintosh, it felt like the right decision for her and her family.

“Life with a CGM and insulin pump is wonderful,” she said. “They pair and work together hand in hand, allowing my blood sugars to stay in control. My A1C is exactly where I want it. Technology has made living with diabetes much more manageable.”