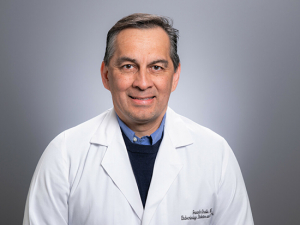

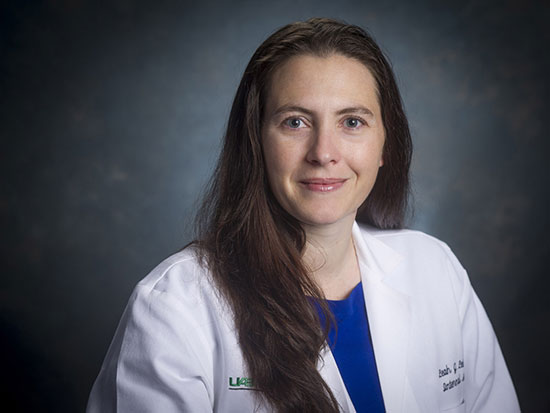

"Once I had the skillset, I found out interacting with patients with substance-use disorder is not only easy, it is phenomenally rewarding," said Leah Leisch, M.D., medical director of Substance Use Services at UAB Beacon Recovery Services. "I love my job, because these patients want badly to get better, and we have tools to help."The patient had a desperate look in his eyes as he approached Leah Leisch, M.D., in the hospital hallway, drawn by her white coat. "He said, 'Doc, do you prescribe suboxone? Can you please prescribe some for me?'" recalled Leisch, who was then a young hospitalist and now is assistant professor in the departments of Medicine and Psychiatry and medical director of Substance Use Services at UAB Beacon Recovery Services. "I politely explained to the patient that I did not. And, I thought to myself, “I am so glad I don't — that is a mess,'" Leisch said. "There are a lot of internists out there who don't want to deal with this disease: it is messy."

"Once I had the skillset, I found out interacting with patients with substance-use disorder is not only easy, it is phenomenally rewarding," said Leah Leisch, M.D., medical director of Substance Use Services at UAB Beacon Recovery Services. "I love my job, because these patients want badly to get better, and we have tools to help."The patient had a desperate look in his eyes as he approached Leah Leisch, M.D., in the hospital hallway, drawn by her white coat. "He said, 'Doc, do you prescribe suboxone? Can you please prescribe some for me?'" recalled Leisch, who was then a young hospitalist and now is assistant professor in the departments of Medicine and Psychiatry and medical director of Substance Use Services at UAB Beacon Recovery Services. "I politely explained to the patient that I did not. And, I thought to myself, “I am so glad I don't — that is a mess,'" Leisch said. "There are a lot of internists out there who don't want to deal with this disease: it is messy."

The story of her encounter in the hospital hallway is part of what Leisch calls "my confession" — the road that led her to focus on treating substance-use disorder. Flash forward a few years after that incident, and Leisch was working in a primary care clinic. She was responsible for training medical residents and hoping to interest them in a specialty that is chronically understaffed. "So many of our patients were aging and on chronic pain medicine," Leisch said. "They were having a lot of complications from being on the medicines and not much benefit, yet, it was so hard to get them off. I ended up taking care of many of these patients because they were exhausting the residents. It was giving them a negative impression of internal medicine."

At first, it wasn't easy for Leisch, either. "I started doing it, and I was terrible," she said. "But I discovered the patients weren't the problem. The problem was me. I was not trained how to screen for and identify substance-use disorder and how to respond when I saw it. Once I had the skillset, I found out interacting with patients with substance-use disorder is not only easy, it is phenomenally rewarding. I love my job, because these patients want badly to get better, and we have tools to help."

An epidemic worsens during the pandemic

The opioid epidemic that was breaking over the country pre-COVID did not give way to the new pandemic. In fact, overdose deaths in Jefferson County were up 100% in 2020 from 2019, "and the first quarter of 2021 is even higher still," Leisch said. Nationwide, overdose deaths reached 93,000, the highest ever recorded in a 12-month period, in 2020. "The primary driver of these deaths was a dramatic increase in the availability of synthetic opioids derived from fentanyl," said Frank Pallone, a representative from New Jersey and chair of the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health in a hearing on the opioid epidemic April 14, 2021.

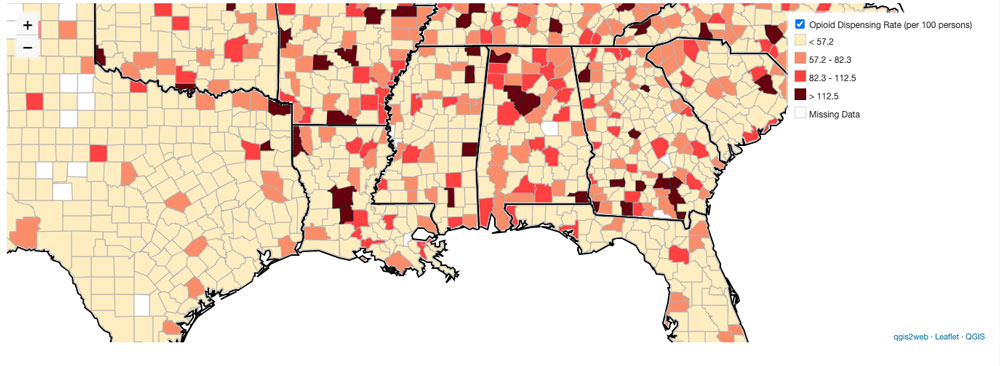

A CDC map of county-level opioid dispensing rates in Alabama and surrounding regions in 2019.

A CDC map of county-level opioid dispensing rates in Alabama and surrounding regions in 2019.

Fentanyl, which is incredibly powerful yet relatively easy to manufacture, can kill in minute amounts. Many substance users do not know how to measure their dose safely or are unaware that the cheaper fentanyl has been added to their heroin or cocaine purchases, which increases the likelihood of a fatal overdose.

The increase in overdoses “and a growing sense the supply chain is unsafe” has led to an influx of patients seeking medication for opioid-use disorder, Leisch said. “Here in Alabama, I would say that some of the influx is also driven by a growing acceptance of medications for opioid-use disorder as a true and viable form of treatment. The more others accept the science behind medications for opioid-use disorder, the less stigma there is to keep patients from coming for help.”

The good news, said Leisch, is that there are ways for primary care doctors — and people who love people with substance-use disorder — to lower the toll. Unfortunately, Leisch said, “only a small number of physicians in Alabama are waived to prescribe buprenorphine, and far fewer actually prescribe it.”

"The big takeaway from my past few years of learning about treating addiction as a primary care provider is that patients who struggle with addiction and die can't recover, and death can happen quickly," Leisch said. “I once had a patient reach out to clinic to establish care. She desperately wanted help stopping heroin use. She called on a Thursday, and I already had multiple patients overbooked on that day. I asked that she be added on to my schedule for Monday. She did not come to the appointment, and we learned from other clinic patients that she had died of an accidental overdose over the weekend. It is a terrible feeling to wonder if she would still be alive if I had just squeezed one more patient onto my already overbooked schedule. This highlights the need to be flexible and provide the most timely care possible.”

At the same time, however, “the volume of patients seeking help is just too great for the few providers offering it,” Leisch said. “We desperately need all of primary care to be prepared to diagnose opioid-use disorder and initiate medications for opioid-use disorder, even if they refer to addiction clinics for follow-up care. If primary care can at least keep the patient alive long enough to get them to treatment they should do that, and one of the best ways to do that is to get them on medication-assisted therapy."

Story continues after box

The tools to help

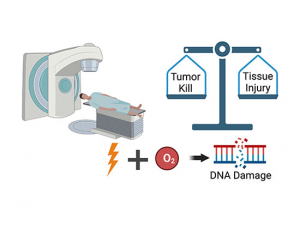

There are three primary medications used to help patients escape from the neurochemical bonds that are part of opioid use disorder: methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone. In a recent edition of the UAB MedCast, a continuing education podcast for physicians, Leisch explained how they work and why doctors need to know about them.

Opioids act on receptors in the brain known as mu opioid receptors to boost production of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Rising dopamine levels can bring happiness or joy in patients, as well as relief from pain.

"Addiction is difficult in that the brain tends to focus on the thing that relieves its suffering," Leisch said. For patients with substance-use disorder, many of whom are coping with chronic pain, that focus is fixed on opiates. One of the reasons medications for opioid-use disorder are effective is they are capable of relieving that craving for many patients. "The other reason these medicines are used is because they’ve done many studies where they look at patients who’ve received medication-assisted treatment versus those who do not and they look at the risk of overdose following them for a year or two; the patients who receive medication-assisted treatment are much less likely to die than those who do not," Leisch said. "That’s the main reason that [they] get prescribed now."

Methadone

Methadone is the best-known medication for opioid-use disorder. Like opioid drugs, it fully activates mu opioid receptors, "meaning the more you take, the more receptor activation you get and the better you feel," Leisch said. "There is some potential for misuse, although it's a slow-acting opioid [compared with opioid drugs] and it doesn't provide that immediate euphoria that other opioids provide. Because of this potential for misuse, "when methadone is provided for addiction therapy, it has to be done in a federally registered addiction treatment center," Leisch said (see below). "The patient takes a liquid dose of methadone directly in front of a nurse who is watching them take it." (Occasionally, patients who have been in treatment for a long time and have a history of negative urine drug screens are allowed to take doses home. "That's a privilege that they earn," Leisch said.)

Who can prescribe methadone? Methadone can only be dispensed by a treatment program certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), part of the Department of Health and Human Services. Because patients must be able to get to a methadone clinic daily, this treatment can be problematic for people who cannot afford transportation or have lost their licenses due to previous interactions with the law.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone blocks the mu opioid receptor, preventing an opioid drug from activating the dopamine rush. "It helps prevent some of the cravings," Leisch said. And if a patient "were to relapse and use while taking it, they're less likely to overdose," because access to the mu opioid receptors is blocked.

"The one downfall to naltrexone is that because it is an antagonist, it doesn’t provide any activation of the mu receptor and will actually kick other opioids off the receptor,” Leisch said. “This means if a person has any opioids in their system when they take their first dose of naltrexone, they will become violently ill. This is why patients have to abstain from all opioids for at least seven days before beginning naltrexone. That can be hard for many people. In addition, since it does not activate the receptor, naltrexone provides no pain relief or other positive feelings. Sometimes it’s hard to get patients to continue taking it. Once they’re off the naltrexone, they’re actually at higher risk of overdose. So the idea is if you’re going to start someone on naltrexone you need to be monitoring them and making sure they’re staying on their medicines.”

Who can prescribe naltrexone? Naltrexone can be prescribed by any provider with no special license, Leisch said. Patients must have been off opioids for at least seven days before beginning naltrexone therapy. “Really great candidates for naltrexone therapy are people who can’t take agonist therapy [such as methadone], like doctors or pilots, who just wouldn’t be allowed to because of the regulations of their employment,” Leisch said. “In that case, naltrexone has a wonderful 80% rate of helping people stay in long-term abstinence."

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial mu opioid receptor agonist. That means it works on the same receptor as opiate drugs and methadone, “only with less activity,” Leisch said. “So even if you take lots and lots and lots of buprenorphine, you’ll never get full activation of the receptor,” and that makes buprenorphine less prone to misuse and less likely to result in overdose.

Buprenorphine comes in two formulations: by itself and “paired with naloxone, which is a reversal agent for opioids,” Leisch said. (Suboxone is the trade name for buprenorphine/naloxone.) It is taken under the tongue, “and when it’s taken appropriately the naloxone is not absorbed,” she said. “Were the patient to try and dissolve it and inject it or do something inappropriate with it, then they would absorb the naloxone with their buprenorphine dose and effectively give themselves the reversal agent with the buprenorphine. So there’s an abuse deterrent mechanism that’s built in.”

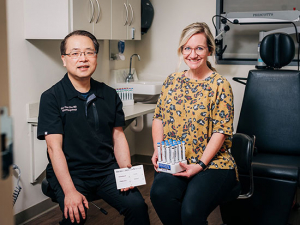

Who can prescribe buprenorphine? Buprenorphine “can be prescribed by any provider who applies to obtain an X-waiver,” Leisch said. Recent changes allow any provider interested in treating patients with OUD to apply for a waiver to treat up to 30 patients without any special training. If providers want to treat more than 30 patients with buprenorphine for OUD, they have to complete an eight-hour training. This training is available online from SAMHSA. Leisch leads X-waiver training sessions two times per month in which she also explains how providers can become comfortable screening for and diagnosing opioid use disorder. Find upcoming dates and enroll here.

Story continues after box

Which treatment is best?

Studies have shown that methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone are equally effective at reducing illicit opioid use, Leisch said. “Methadone is most effective at retaining people in treatment, partly because it is hard to get lost when you have to go every day.”

The X:BOT trial, published in the journal Lancet in 2017, showed poorer results for the once-a-month intramuscular injections of naltrexone than for sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone, Leisch said, but that was because it was harder to initiate the naltrexone treatment in the study. “But if you look at the people who actually started naltrexone and completed the study, it's as effective once you get a person on it,” Leisch said. “That's why we often reserve naltrexone for the inpatient setting and the residential setting, because those first seven days are hard. If someone found it easy to not use for seven days, they often decline medication-assisted treatment.”