This is the fifth in a series of profiles of the finalists in the UAB Grand Challenge. The initiative, a key component of Forging the Future, UAB’s strategic plan, launched this past summer and inspired more than 75 initial entries from teams across campus. The results were announced on April 30, with the Healthy Alabama 2030 project selected as the inaugural UAB Grand Challenge winner.

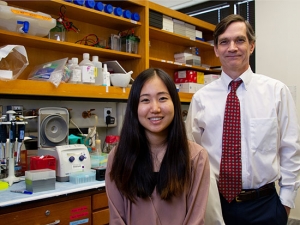

The REACH project, led by Nursing's Jacqueline Moss (left) and Medicine's Eric Wallace, aims to build a "collaborative laboratory" in which innovative approaches to health-care technology can be tested.In many parts of Alabama, the most important piece of the health-care infrastructure is made of asphalt. Whether it’s emergency intervention after a car accident or stroke or the all-important follow-up from a cancer diagnosis or heart surgery, help means a multi-hour drive to the nearest big city. Jacqueline Moss, Ph.D., and Eric Wallace, M.D., have a better solution in mind: health-care technology that lets patients get care in their hometowns — or even in their own homes. The project could also be a lifeline for ailing rural hospitals and economies.

The REACH project, led by Nursing's Jacqueline Moss (left) and Medicine's Eric Wallace, aims to build a "collaborative laboratory" in which innovative approaches to health-care technology can be tested.In many parts of Alabama, the most important piece of the health-care infrastructure is made of asphalt. Whether it’s emergency intervention after a car accident or stroke or the all-important follow-up from a cancer diagnosis or heart surgery, help means a multi-hour drive to the nearest big city. Jacqueline Moss, Ph.D., and Eric Wallace, M.D., have a better solution in mind: health-care technology that lets patients get care in their hometowns — or even in their own homes. The project could also be a lifeline for ailing rural hospitals and economies.

Moss and Wallace are co-principal investigators for REACH — Reengineering Equal Access to Comprehensive Healthcare. This project, a UAB Grand Challenge finalist, lays out “a framework to transform how people in Alabama access health care,” explained Wallace, who is medical director for UAB eMedicine, the health system’s telemedicine initiative, and an associate professor in the Department of Medicine. “Alabama has some of the worst health outcomes in the country, and our No. 1 problem is access to care.”

Wired for success

Moss, Wallace and their team view REACH as a “collaboratory” — a collaborative laboratory in which all the key players in the care continuum can field-test promising methods to overcome geographic barriers. The team began by building bridges to those partners. With the $30,000 planning grant they received from the UAB Grand Challenge committee, the team canvassed providers and patients in rural areas about their top needs. “The major barriers they identified were lack of transportation, lack of access to specialty care, lack of technology infrastructure and rural hospital closures,” said Moss, professor and associate dean for Technology and Innovation in the School of Nursing. The team also held a summit with UAB faculty across disciplines and representatives of key statewide companies and government groups including Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama, Alabama Power and Alacare Home Health and Hospice.

| “To really make an impact on health outcomes in Alabama, we have to reach patients where they get sick. That’s at home rather than in the hospital. If we send in nurses fully equipped with telehealth technology, the patient’s home becomes the subspecialty clinic.” |

“Small hospitals are closing across Alabama at an alarming rate,” Moss said. “Eighty-five percent of rural hospitals in the state are in the red, according to the Alabama Hospital Association.” Meanwhile, as the population ages “people are needing access to more care in their homes.” Solutions for these issues have already been pioneered at UAB, Moss adds. “We know that technology can really make a difference in people’s lives.”

Health care close to home — or at home

To demonstrate this, the REACH team has lined up a series of projects. At John Paul Jones Hospital in Camden, in the heart of the Black Belt, nurse practitioners would be trained to deliver care with telesupport from ER doctors at UAB. (UAB eMedicine already has expanded delivery of much-needed services for stroke and critical care to 60 of Alabama’s 67 counties in a telehealth partnership with the state Department of Public Health.) “That allows patients to stay close to home and close to their families,” Wallace said. “Instead of driving hours away from home and having loved ones miss work, patients can get the care they need with family members that love them right there.” Supporting rural hospitals has an important economic effect as well, Moss added, by “protecting good jobs in these communities” and helping draw new residents. “Who wants to retire or open a business where there is no health care?”

A partnership with home-health provider Alacare would bring computers, hotspots and digital stethoscopes into the homes of people recently hospitalized for congestive heart failure or COPD in order to reduce readmissions. And a collaboration with Federally Qualified Health Centers would use remote patient monitoring equipment to help patients with uncontrolled diabetes and obesity get better access to care and decrease unnecessary hospitalizations. “To really make an impact on health outcomes in Alabama, we have to reach patients where they get sick,” Wallace said. “That’s at home rather than in the hospital. If we send in nurses fully equipped with telehealth technology, the patient’s home becomes the subspecialty clinic.”

Preparing a new workforce

The project also includes several education components. One would set up a standardized training exam for future doctors, nurses, social workers, dentists and other care providers, “to make sure they really know how to provide a video visit,” Moss said. Another would establish an interdisciplinary honors designation in health-care technology for undergraduate students and offer them an experiential service-learning course in which they could work on one of the funded REACH Collaboratory projects. Meanwhile, graduate fellowships and an innovation and entrepreneurship series would serve to attract students, researchers and clinicians to focus on health-care technology needs.

The project also includes several education components. One would set up a standardized training exam for future doctors, nurses, social workers, dentists and other care providers, “to make sure they really know how to provide a video visit,” Moss said. Another would establish an interdisciplinary honors designation in health-care technology for undergraduate students and offer them an experiential service-learning course in which they could work on one of the funded REACH Collaboratory projects. Meanwhile, graduate fellowships and an innovation and entrepreneurship series would serve to attract students, researchers and clinicians to focus on health-care technology needs.

“To transform health care, we have to train a new workforce,” Wallace said. “There are already openings for telemedicine physicians all over, and telenursing is on the rise.” The School of Nursing now trains all students, undergraduates and graduates, in telemedicine. “This is going to be a career path,” Wallace said. “And it’s really changing the whole health system. Where does telehealth fit? How do we use technology to make the system more efficient and make people’s lives better? We have to determine the models that work, and it has to start at UAB because no other institution in the state can lead the way as we can.”

“That’s why the Grand Challenge is so exciting,” Moss said. “There are pockets all over campus where people are working on this, but the Grand Challenge has allowed us to connect the dots. We’re already having an impact. This would move things forward and change peoples’ lives.”