Patricia Drentea's new book is the first U.S.-focused text to examine the likely outcomes of the social changes of the past few decades.The forces of social change in the United States have been accelerating since the Industrial Revolution, but the past few decades have been particularly hectic, including the rise of the internet, relaxation of traditional gender roles and globalization. The expectations and experiences of the generations alive today are diverging ever further from those of our parents and grandparents. So, what will the world be like when the millennials — and their kids — reach old age?

Patricia Drentea's new book is the first U.S.-focused text to examine the likely outcomes of the social changes of the past few decades.The forces of social change in the United States have been accelerating since the Industrial Revolution, but the past few decades have been particularly hectic, including the rise of the internet, relaxation of traditional gender roles and globalization. The expectations and experiences of the generations alive today are diverging ever further from those of our parents and grandparents. So, what will the world be like when the millennials — and their kids — reach old age?

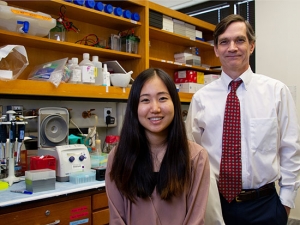

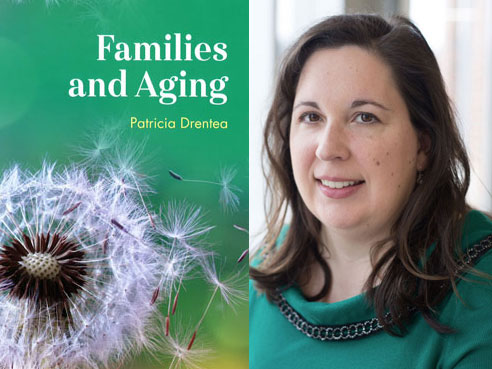

That is the weighty question running through “Families and Aging,” a new textbook written by Professor Patricia Drentea, Ph.D., director of graduate studies in the Department of Sociology. Drentea has studied both subjects for more than 25 years and teaches a course of the same name for undergraduates. But there has been no U.S.-focused text summarizing and analyzing the likely outcomes of the social changes of the past few decades.

Drentea addresses diversity in American society, changing gender roles, the increasing average age of parenthood, work and retirement concerns plus health and caregiving. “This book looks at the ramifications of our social patterns in this country,” Drentea said. These patterns and trends first are identified by demographers, she explains. The sociologist’s role is to consider the effects. “I try to predict what the next 50 years will bring,” she said.

Life on the ‘beanpole’

For example, 10 percent of the adult population today is single. By 2030, according to estimates, this figure will rise to 25 percent. Today, about 18 percent of women ages 40-44, when most childbearing is complete, have not had any children. That trend is expected to increase, Drentea notes. And even families with children will have fewer siblings as more women wait until after their careers are established to have children. “It’s what’s known as the beanpole structure of families today,” Drentea said. “More generations are alive at any one time, but there isn’t the same horizontal band that there once was.”

Trace these trends into the future and you see “really strong ramifications,” Drentea said. “With the extension of life expectancy, more people will be living to 100 and a good number of people will make it past ages 80-85, which is usually when people start needing help. Most people, even today, don’t go into assisted living; they are cared for by family. But if you are single with no kids, there could be no one at the end who will help with care.”

Voices behind the data

“This book looks at the ramifications of our social patterns in this country.… I’m hoping it will help social workers, sociologists, nurses, psychologists and other clinicians in practice think through some of these issues.” |

Each chapter of “Families and Aging” includes an overview of sociological theory on the topic in question, a vignette drawn from in-depth interviews with representative individuals, as well as Drentea’s own statistical analysis of the phenomenon, based on U.S. Census data. It is designed to be a higher-level undergraduate or introductory graduate student textbook, Drentea said. “I’m hoping it will help social workers, sociologists, nurses, psychologists and other clinicians in practice think through some of these issues.”

Six trends to watch

In her research for her book, Drentea says she found several new patterns to be particularly intriguing:

LATs (Living Apart Together): These are older adult couples who keep two separate homes. “This may be for financial reasons — or simply not wanting to meld all their stuff. It also could be because of their kids,” Drentea said. “Their adult children may have issues with them living together, so to keep it simple they keep their own homes.”

Extending the sunset years: “With longer lifespans comes longer retirement, although because that’s more for upper-class folks, quit work is a better phrase. That could be 30 years of free time, and it needs to be filled with something. There’s grandparenting. But also travel, being active in church and spending time online. Plus shopping — that’s a very American activity.”

Reconstituted families…: “Negotiating divorces and remarriages results in a myriad of forms of step-family situations. You have step-grandparents, for instance — and we don’t really have a good word for that. There are varying degrees of obligation and love, depending on when the couples got together. There’s a theory by a famous sociologist, Andrew Cherlin, that in the second marriage, everything has to be negotiated. It’s the same with second families.”

…and globalized relationships: “Our children will interact with people all over the world, which will lead to more intermarriage among different national and ethnic groups. What’s that like when you’re from Alabama and marrying a Hindu? How are you going to handle birth, death, weddings — all the big things that families do together — with very different cultures and religions? There’s more to negotiate.”

Men as caregivers: “Women by far do most of the caregiving; usually the daughter first and on in a female line. But more men are and will be caregiving. Men might have always helped around the house, doing odd jobs or handling finances, but the reality of the aging body gets into some uncomfortable body issues: Do you bathe your mother?”

Parenting changes: “There is a gradual loosening of expected gender behavior. Men are becoming more active parents, and we will see increased equality in parenting. I don’t think we’ll have another generation of men who don’t spend significant time in the trenches of raising their kids, don’t know how to cook and can’t do their own laundry.”