This is the second in a series of profiles of the finalists in the UAB Grand Challenge. (Read the first story here.) The Grand Challenge initiative is a key component of Forging the Future, UAB’s strategic plan. It was launched this past summer and inspired more than 75 initial entries from teams across campus. The results were announced on April 30, with the Healthy Alabama 2030 project selected as the inaugural UAB Grand Challenge winner.

Karen Cropsey has seen opioid overdoses devastate communities across Alabama. Her team's Grand Challenge proposal aims to turn the tide through clinical intervention, education and research efforts.The darkness of drug addiction is often described as the “depths of despair.” The statistics surrounding the nation’s opioid epidemic are indeed bleak. This is a problem so big that for the past three years it has dragged down life expectancy for the average American — the first such sustained drop in life expectancy since 1917. But Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., who has spent 20 years studying addiction treatments and behavior change, has seen how these interventions can make a difference. “You can get better,” said Cropsey, the Vivian Conatser Turner Endowed Professor in Psychiatry at UAB. “That message gets lost.”

Karen Cropsey has seen opioid overdoses devastate communities across Alabama. Her team's Grand Challenge proposal aims to turn the tide through clinical intervention, education and research efforts.The darkness of drug addiction is often described as the “depths of despair.” The statistics surrounding the nation’s opioid epidemic are indeed bleak. This is a problem so big that for the past three years it has dragged down life expectancy for the average American — the first such sustained drop in life expectancy since 1917. But Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., who has spent 20 years studying addiction treatments and behavior change, has seen how these interventions can make a difference. “You can get better,” said Cropsey, the Vivian Conatser Turner Endowed Professor in Psychiatry at UAB. “That message gets lost.”

In 2015, Cropsey and colleagues raised more than $11,000 to purchase overdose-reversing naloxone kits for concerned family and friends of at-risk opioid users in the Birmingham area. That project’s success led to more funding — and nearly 50 lives saved so far.

“It’s the first time I did a project where people who were affected reached out to us,” Cropsey said. “I’ve done projects where I’ve helped people quit smoking, but the consequences play out over 20 years. Someone can take a drug and not know what’s in it and be dead within an hour.” Cropsey got one email that said: “I’m so glad to have gotten that naloxone kit. That saved my brother’s life.”

More than a shot in the arm

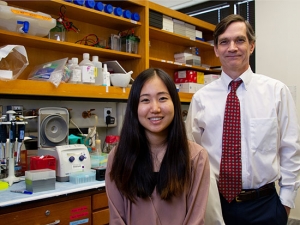

Naloxone alone can’t stop the opioid crisis. That’s why Cropsey and dozens of other UAB researchers and clinicians developed the “Opioid Overdose Prevention and Treatment” project, one of six finalists in the UAB Grand Challenge competition. “I wanted to do something about this major issue,” said Cropsey, who is principal investigator for the project. “Addiction is a complicated disease that encompasses many social, biological and economic issues. It really needs to be addressed comprehensively.”

The proposal focuses on preventing opioid overdoses through clinical intervention, education and research, Cropsey explained. Each element is necessary to alter the current grim statistics. Across Alabama, barely more than a quarter of people estimated to have opioid-use disorder are engaged in care. Only 10 percent are receiving evidence-based medication-assisted therapy, and only about 5 percent are abstinent from opioids after six months.

Changing the paradigm

Laboratory and clinical research will focus on better identification of patients at risk for an opioid overdose and finding new treatments for opioid addiction. Efforts also will focus on developing alternatives to opioids for chronic pain, reducing the need for opioid prescriptions. “A lot of this crisis initially resulted from the way we treat chronic pain in the United States,” Cropsey said. “There need to be other treatments beyond opioids, because these medications were never developed to be used over a long period of time for chronic pain.”

| The opioid epidemic has crossed all social, racial and socioeconomic lines, “with most families either personally affected or knowing someone who is affected. This project has the potential to make a real impact across our state and beyond." |

The project’s planned education and prevention efforts run the gamut from grade school to adulthood. “We need to do a better job educating the American public that just because you have pain doesn’t mean you need opioid medications,” Cropsey said. “There are alternatives, including non-opioid pain medications, physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, yoga and meditation.”

Clinician education programs will help providers recognize prescribing habits that can put patients at risk for addiction. Dentists are one focus area. “They are often on the front lines,” Cropsey said. “It turns out that most adolescents are first exposed to opioids by a dentist. They have their wisdom teeth extracted and that’s how it starts.”

Policy initiatives in the project aim to expand harm-reduction initiatives in Alabama, including wider naloxone distribution and syringe service programs. The project also includes training to build a workforce that can provide care for those already affected by opioid addiction. “Addiction is a medical disease and needs to be treated with evidence-based models of treatment rather than treated like a moral failure,” Cropsey said.

Policy initiatives in the project aim to expand harm-reduction initiatives in Alabama, including wider naloxone distribution and syringe service programs. The project also includes training to build a workforce that can provide care for those already affected by opioid addiction. “Addiction is a medical disease and needs to be treated with evidence-based models of treatment rather than treated like a moral failure,” Cropsey said.

Moving toward a common goal

As word about the project spread, “we had more and more people wanting to join and be involved,” Cropsey said. Team members represent the schools of Medicine, Public Health, Health Professions, Dentistry, Engineering and the College of Arts and Sciences. “The Grand Challenge is a great idea that has really helped us bring together a very diverse group of experts,” she said. “It gets people moving in the same direction with a common goal, each of them approaching it from a different angle.”

The opioid epidemic has crossed all social, racial and socioeconomic lines, “with most families either personally affected or knowing someone who is affected,” Cropsey said. “This project has the potential to make a real impact across our state and beyond. We’re talking about the difference between life and death.”