Jessica Hoffman and her dog, Aspen. Hoffman received a prestigious K99/R00 Pathway to Independence award (known as a "kangaroo") from the NIH's National Institute on Aging. She is studying the metabolomes of mice, dogs and fruit flies to try to understand why size has a major impact on longevity across species.Whether you are a flea, an elephant or a postdoctoral researcher, eventually all things come to an end.

Jessica Hoffman and her dog, Aspen. Hoffman received a prestigious K99/R00 Pathway to Independence award (known as a "kangaroo") from the NIH's National Institute on Aging. She is studying the metabolomes of mice, dogs and fruit flies to try to understand why size has a major impact on longevity across species.Whether you are a flea, an elephant or a postdoctoral researcher, eventually all things come to an end.

Fleas and elephants generally aren’t interested in their career paths. Postdocs, who by definition are on temporary assignment, can think of little else.

Jessica Hoffman, Ph.D., is an evolutionary biologist in the lab of Department of Biology Chair Steven Austad, Ph.D., who also directs the UAB Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging. This year, Hoffman joined elite company when she received a coveted K99/R00 Pathway to Independence grant from the National Institutes of Health. The award will allow her to start her own lab to take on a puzzling question in aging research: Why are size and lifespan interconnected?

“Across species, the larger you are the longer you live,” Hoffman said. Fruit flies last 40 to 50 days. Dogs live up to 20 years. Elephants can reach 70.

“But within species, it’s the opposite,” Hoffman said. “Ponies live longer than horses, small dogs live longer than large ones. We see that in every species with a significant size variation. What I’m interested in is: Is there a conserved pathway for this?”

A kangaroo’s leap

This question, and Hoffman’s previous work with Austad, convinced the National Institute on Aging to award her one of the coveted K99/R00 grants in April 2019. Known as “kangaroos,” these large, multi-year funding awards were created to help rising stars “launch competitive, independent research careers,” according to the NIH.

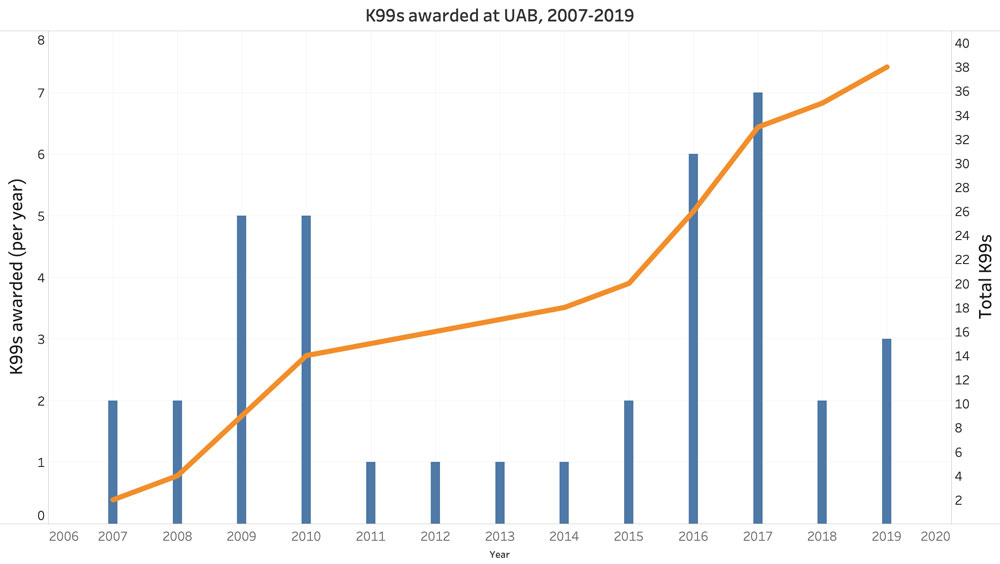

Competitive is the key word. In 2019, only 262 K99s were awarded to postdocs at 92 institutions. UAB was one of 34 institutions with three or more awardees. Eman Gohar, Ph.D., was selected by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for her project, Sex Differences in Renal Sodium Handling, with Department of Nephrology professors Edward Inscho, Ph.D., and David Pollock, Ph.D., as mentors. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute selected Malgorzata Kasztan, Ph.D., for The Role of Endothelin–1 in Tubular Injury in Sickle Cell Disease, with nephrology Professor Jennifer Pollock, Ph.D., and Associate Professor Jaroslaw Zmijewski, Ph.D., from the Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, as mentors.

"Ponies live longer than horses, small dogs live longer than large ones," Hoffman said. "We see that in every species with a significant size variation. What I’m interested in is: Is there a conserved pathway for this?

"Ponies live longer than horses, small dogs live longer than large ones," Hoffman said. "We see that in every species with a significant size variation. What I’m interested in is: Is there a conserved pathway for this?

Making it in research

Hoffman is the first trainee in the Department of Biology, and the College of Arts and Sciences as a whole, to receive a K99 while at UAB. But she is not the only kangaroo in her department. Melissa Harris, Ph.D., an assistant professor in biology who joined UAB in 2016, was awarded a K99 in 2014 while at the National Human Genome Research Institute for her research on gray hair and aging.

“People who get these are almost guaranteed to get a faculty position in the near future,” Austad said. “Jessica is exactly the kind of person that we look to hire when we are recruiting. She’s really on her way to an outstanding faculty career.”

The K99/R00 is a “very prestigious award,” said Jennifer Croker, Ph.D., senior executive administrator of UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science. “It lays out a nice runway for a scholar to establish their independence,” with two or three mentored K99 years followed by a couple of R00 years as a junior faculty member. The NIH’s own research shows that receiving a K99/R00 makes an investigator very likely to receive an R01, the four- to five-year Research Project Grant that is, in Croker’s words, the “you-made-it signal” for a scientist’s research career.

Getting a K99 takes a great idea, but it also takes superior communication skills. Hoffman says she benefitted from several courses she took through the UAB Office of Postdoctoral Education, which offers formal education, mentoring and other support to UAB’s 250-plus postdoctoral trainees. (See “Fueling postdoc success” below.) She also credits Austad, a former journalist who has written several books and columns in the popular press, with helping her share her vision with grant reviewers. (See “Where’s the hook?” below. Story continues after the box.)

Small to big

Hoffman’s project is called The Metabolic Consequences of Small Size and Long Life. It targets the pathway that turns the essential amino acid tryptophan into kynurenine. This is the same tryptophan made famous as a source of post-Thanksgiving meal lethargy — although that is a myth, Hoffman said. In reality, tryptophan is the starting point for the synthesis of the neurotransmitters serotonin and melatonin. But disruption in the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway also has been linked to inflammation, depression and neurodegenerative disease.

“Tryptophan kept coming up over and over as I analyzed different species,” Hoffman said. “We did a study last year in marmosets, looking at which animals died over two years. We found that animals who had lower levels of tryptophan were more likely to die.”

Working with Austad and Liou Sun, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Biology who studies growth hormone-disrupted mice, Hoffman found that kynurenine levels were higher, and tryptophan levels lower, in both small dogs and small mice, compared to their larger counterparts. Studies by other researchers have found that kynurenine is higher in patients with Alzheimer's and the entire tryptophan-kynurenine pathway is dysregulated in Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases. "But we still don't know the causative agents," Hoffman said.

Everything is connected

With her K99/R00 grant, Hoffman will study the metabolomes of mice, dogs and fruit flies “to tease apart what’s going on,” she said. She will determine what happens to the lifespans of fruit flies when tryptophan metabolism genes are manipulated, for instance, and aims to “provide new hypotheses about potential interventions to improve lifespan and healthspan,” according to her grant application.

“We really need a biomarker for aging; something you could measure early in midlife to predict what’s going to happen to you,” Hoffman said. “This pathway could potentially do that.”

Although she will be working with Sun to learn molecular biology techniques, the majority of Hoffman’s research involves statistical analysis of mass spectrometer data, focused on the relatedness of protein and metabolite networks. The correlated network structures among proteins and metabolites tend to break down with age. The trick is to figure out which of these matter. “We get data on 2,000 to 3,000 metabolites in the body and a lot of them change with age,” Hoffman said. “Do all of them matter in aging? Which ones are causative and which ones are by-products? That’s the hard thing to figure out.” Although she is working with mice and fruit flies, most of the figuring happens in front of her computer, Hoffman said. “I sit and analyze data in the program R all day.”

“Jessica is a scientist who loves data more than almost anyone else I know,” Austad said. “That has really formulated her research strategies — large quantities of data and complex ways to analyze them.”

Aspen is one of the reasons Hoffman decided to focus on research into aging.

Aspen is one of the reasons Hoffman decided to focus on research into aging.

Dogging it

“Most of my experiments are looking at natural variation, which is to say there is no experiment,” Hoffman explained. She is particularly interested in dogs. She has written a series of scientific papers on companion dogs as models of aging with Austad and Daniel Promislow, Ph.D., her doctoral advisor at the University of Georgia who now is at the University of Washington.

In Do Female Dogs Age Differently Than Male Dogs?, the answer was, surprisingly, not really. Hoffman, Austad and colleagues Dan O’Neill, DVM, at the Royal Veterinary College in the United Kingdom, and Kate Creevy, DVM, at Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine, conducted the “most extensive analysis of sex differences in dog aging to date,” they wrote, based on the veterinary records of more than 83,000 canines. Females live longer than males in all human populations, the authors pointed out, as well as in Old World apes and monkeys, pilot whales, red deer, African lions, pipistrelle bats and prairie dogs. But they found few sex differences in longevity and in causes of death in their dog data. Among unneutered dogs, males lived slightly longer than females; the effect was reversed for neutered dogs.

By slowing aging in dogs, researchers can get a clearer picture of the benefits of doing the same in humans, including reducing age-related diseases, Hoffman, Austad, Promislow and co-authors argued in another paper, The Companion Dog as a Model for the Longevity Dividend.

Dogs, including her own American Eskimo mix, Aspen, are “partly what got me interested in aging,” Hoffman said. “I need my dog to live forever.” She isn’t the only one. Dog owners are remarkably eager to take part in research that may one day extend their companions’ lifespans, Hoffman said. “People love dogs.”

Promislow runs the Dog Aging Project, which aims to enroll “10,000 dogs and their owners to identify factors critical to improving healthy lifespan,” according to its website. Hoffman plans to continue collaborating with Promislow’s team on future studies.

Getting started

“I’ve always been interested in biology,” Hoffman said. Her parents both work in STEM fields — her mother teaches math at a community college and her father is a computer scientist — and she figured she might become a veterinarian. But as an undergraduate at Clemson University she had an advisor who encouraged her to consider research. “That got me into it, and I realized this is actually what I wanted to do,” she said.

Hoffman, who has been involved in science outreach to girls and young women, tells them “we need more women in STEM,” she said. “I tell them it’s awesome and anyone can do it. I tell them that a good foundation in science is useful even if you don’t want to stay in science. It gets you thinking critically. And you don’t have to be some super genius. You just have to be truly interested and a hard worker."

That could be a description of Hoffman herself. Her ultimate career goal “is to do interesting science,” she said. “We’ll see where that leads.”

The K99/R00 grant makes recipients highly sought after by other universities, Austad points out. “We will be really sad to lose Jessica, but this is also how you enhance your reputation, by having really good people come out of your program.”