A new clinical trial at UAB aims to improve cognitive function in patients with "brain fog" and other lingering cognitive symptoms after they have recovered from COVID-19.Even after their bodies have cleared the virus that causes COVID-19, many patients experience long-term effects. One of the most troubling is a change in cognitive function — commonly called “brain fog” — that is marked by memory problems and a struggle to think clearly. A new clinical trial at UAB is testing a proven rehabilitation method to remedy that.

A new clinical trial at UAB aims to improve cognitive function in patients with "brain fog" and other lingering cognitive symptoms after they have recovered from COVID-19.Even after their bodies have cleared the virus that causes COVID-19, many patients experience long-term effects. One of the most troubling is a change in cognitive function — commonly called “brain fog” — that is marked by memory problems and a struggle to think clearly. A new clinical trial at UAB is testing a proven rehabilitation method to remedy that.

A report on 120 patients in France, published in October 2020, found that more than a third had memory loss and 27% had cognitive difficulties months after recovering from COVID-19. In another study, a hospital network in Chicago reported that, among 509 patients, nearly a third experienced altered mental function; of these, 68% were unable to handle routine daily activities such as cooking or paying bills.

What is it like to live in the fog?

One physician described it as akin to the fuzzy-headed feeling the day after a sleepless night. A researcher in the United Kingdom, discussing an initial report on more than 84,000 people, said in severe cases it is as if the brain had aged 10 years, almost overnight. Patients talking to the New York Times said “it is debilitating,” “it feels as though I am under anesthesia” and “everything in my brain was white static.” Several described how the brain fog has made it difficult or impossible for them to return to work.

Therapy used around the world

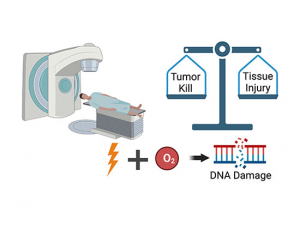

There are no current treatments for brain fog attributed to COVID-19. But a new clinical trial at UAB is testing a proven rehabilitation method with a record of success in restoring lost function. Known as Constraint-Induced Therapy (CI Therapy), it was developed by Edward Taub, Ph.D., University Professor in the Department of Psychology and director of the CI Therapy Research Group, in collaboration with colleagues at UAB. CI is used around the world to help patients regain limb function and language abilities after stroke.

CI Therapy also is used to treat patients with traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis and cerebral palsy, and with anoxial and other brain damage in pediatric patients.

|

Individuals who think they can benefit are welcome to contact the project directly at 205-934-9768 or learn more about the study at uab.edu/citherapy. |

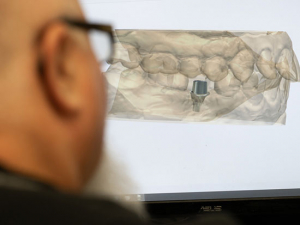

In a host of studies (including patients with stroke, multiple sclerosis, and cerebral palsy) Taub and his longtime collaborator, Professor Gitendra Uswatte, Ph.D., with other members of their research group, have demonstrated the effects of CI Therapy. Using MRI scans, they have shown that the therapy rewires the brain following two weeks of intensive training in the clinic and ongoing practice at home. The improvement in function that results remains, even after years have passed, Taub said.

Some 97% of the thousands of stroke patients who have taken part in CI Therapy have seen meaningful improvement, and the average patient uses his or her affected limb five times more post-therapy than pre-therapy. (In 2014, when the Dalai Lama and experts in neuroplasticity visited UAB for a conference on the topic, one described UAB as “a national treasure” and “the premier place in the world to get treatment for movement problems following stroke.”)

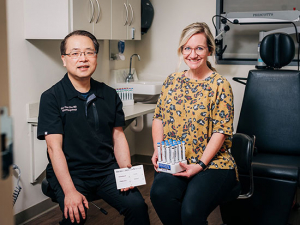

Gitendra Uswatte, Ph.D. (left), and Edward Taub, Ph.D. (right).

Gitendra Uswatte, Ph.D. (left), and Edward Taub, Ph.D. (right). Tackling persistent cognitive impairment

Now, Uswatte explained, “we have turned our attention to patients with persisting cognitive impairment after recovering from COVID-19.” Brain scans showing significant rewiring after CI Therapy had long since convinced Taub and Uswatte that the technique could restore cognitive function in the same way it restored a person’s ability to move their arms or legs. “We found in the motor rehabilitation work that the therapy is effective for a number of different types of brain damage,” Uswatte said.

The researchers first worked specifically on cognitive effects by developing therapy for aphasia, the loss of speech ability that is common after stroke. “At the end of two years, several patients who came in with substantial speech deficits after stroke were back to normal,” Taub said.

During the past several years, the researchers, in collaboration with University Professor Karlene Ball, Ph.D., also in the Department of Psychology, have developed a form of CI Therapy, CI Cognitive Therapy, that combines speed-of-processing training with the procedures they use to transfer improvements made in the lab into patients’ everyday lives. Ball has developed a computer-based speed-of-processing training that has shown remarkable efficacy in helping older people maintain their ability to drive. Up to six years after they have gone through her training, participants reduce their risk of an at-fault crash by half, according to the NIH-funded ACTIVE randomized, controlled multi-site trial.

‘Playing Scrabble again’

In a recently completed pilot study of six participants with cognitive difficulties after stroke, CI Cognitive Therapy brought significant improvements in the participants’ everyday lives, Taub said. Although the results have not yet been published, several of those patients have made “very substantial improvements in carrying out cognitive tasks in their daily life” that are still being maintained as long as 11 months after completing training, Taub said. The patients’ improvements on cognitive tasks during training was not surprising “given our past work in the motor and speech domains,” Taub said. “What is exciting is what has happened since the end of training — the participants have kept improving.”

“Participants tell us they have been able to go back to work, to start preparing food in the kitchen again, to start playing Scrabble again, that type of thing,” Uswatte said. “The therapeutic principles are not specific to a particular condition or type of damage. We would expect that similar mechanisms apply in stroke and COVID-19.” In fact, many patients with COVID-19 appear to have suffered strokes or mini-strokes, Uswatte said.

Clinical trial details

With pilot funding from UAB’s Integrative Center for Aging Research, Taub and Uswatte aim to recruit at least 20 adult patients — anyone age 18 or older who has recovered from COVID-19 but is experiencing memory loss, brain fog or other cognitive issues. Participants will receive the training at no cost. It involves 35 hours of therapy in the clinic, including the computer-based speed-of-processing training and a component called shaping, which involves training simulated cognitive activities in the clinic that are made progressively harder over time.

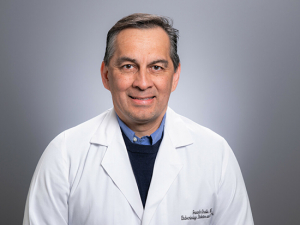

Project Medical Director Victor Mark, M.D., and psychologists Amy Knight, Ph.D., and Megan McMurray, Ph.D., all in the Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, and neurologist Shruti Agnihotri, M.D., a member of the UAB Post-COVID Treatment Program, and psychologist Kristine Lokken, Ph.D., in the Department of Psychiatry, are helping to recruit candidates for the study. Individuals who think they can benefit are welcome to contact the project directly at 205-934-9768 or learn more about the study at uab.edu/citherapy.

Transferring gains to everyday life

Typically, the training is spread across two weeks. Participants often have caregivers who must work or have other obligations, so the training can be conducted during a longer period in some cases, Taub said. At the end of each session, participants are assigned 10 tasks to carry out as homework “that patients use in their everyday lives to focus on transferring the gains they have made in the lab,” Uswatte said. “These are tasks that are important to the person or their quality of life and are going to challenge their cognitive skills.”

The activities might include “cooking a meal with more than three ingredients, starting a conversation, remembering medication, doing the laundry or making out a shopping list,” Taub said. “There are perceived and often real barriers to carrying out cognitive activities. Part of the requirement of the program is that participants have a caregiver or person who lives with them who can prompt them to do this homework when they are at home. We also call them once a week for the first month after the end of training and then once a month for the next 11 months to help participants hold onto their gains.”

The challenge of adapting CI therapy to a new condition is exciting, Taub and Uswatte say. “This isn’t our first rodeo,” Taub said. “We have proved that the therapy works in other conditions. What got us interested here was the fact that current brain-training techniques that aim to help with brain fog work fine in the lab or in the training setting but they don’t transfer robustly to real-life situations. And if it doesn’t transfer to life situations, why bother?”