"At a time like this, when uncertainty is high, that's when entrepreneurs see opportunities," said Patrick J. Murphy, Ph.D., professor and Goodrich Entrepreneurship Chair in the Collat School of Business. The economic news these days can seem grim. Government efforts to rein in soaring inflation are predicted to lead to a recession, which usually means job cuts, fewer raises, and general belt-tightening for companies and employees.

"At a time like this, when uncertainty is high, that's when entrepreneurs see opportunities," said Patrick J. Murphy, Ph.D., professor and Goodrich Entrepreneurship Chair in the Collat School of Business. The economic news these days can seem grim. Government efforts to rein in soaring inflation are predicted to lead to a recession, which usually means job cuts, fewer raises, and general belt-tightening for companies and employees.

But recessions also tend to mark new beginnings. Uber, Airbnb, Square and Venmo all were born during the Great Recession of the late 2000s. Microsoft was founded during the energy crisis of the mid–1970s. “And the time when firm formation rates were at their highest in our country was during the Great Depression,” said Patrick J. Murphy, Ph.D., professor and Goodrich Entrepreneurship Chair in the Collat School of Business. “When larger structures break down, it creates a lot of problems — which call for entrepreneurial responses.”

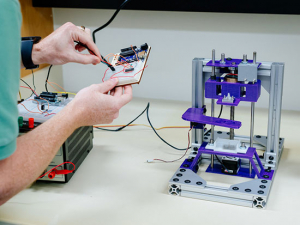

Murphy leads UAB’s J. Frank Barefield, Jr. Entrepreneurship Program, which includes a major and a minor, an MBA entrepreneurship concentration, and a Technology Commercialization and Entrepreneurship Graduate Certificate.

“At a time like this, when uncertainty is high, that’s when entrepreneurs see opportunities,” Murphy said. Launching a business in a tanking economy may seem foolhardy, but successful entrepreneurs do not look at the world in the same way that others do. “Undertaking entrepreneurial action always runs the risk of failure,” Murphy said. “But if one has unique knowledge, the risk is relativized, and one can find a powerful boldness to act. These are the innovators, who are followed by imitators.”

The gateway to UAB’s entrepreneurship program is ENT 270: The Entrepreneurial Mindset. “It can be a life-changing educational experience for students thinking about entrepreneurship,” Murphy said. Mindset — including self-exploration — is important to success as an entrepreneur, he notes. “Knowing yourself and having a changeless sense of who you are — that is one of the keys to navigating uncertainty,” Murphy said. “Entrepreneurship is a discipline. It is not a skillset that can be learned quickly in a short training program. Universities are uniquely suited to deliver that kind of education.”

Murphy shares seven more lessons his students learn below.

Murphy works with students at Birmingham's Innovation Depot. Hear about the J. Frank Barefield, Jr. Entrepreneurship Program at UAB from a student perspective in this video.

Murphy works with students at Birmingham's Innovation Depot. Hear about the J. Frank Barefield, Jr. Entrepreneurship Program at UAB from a student perspective in this video.1. There is no “entrepreneur personality”

Murphy starts out by busting a myth: There is no “entrepreneur personality” or “right stuff,” he said. “Anyone can be an entrepreneur. You can be an introvert, you may not feel particularly daring; but if you believe in the underlying mission of what you are trying to accomplish, and have the right knowledge, it lends boldness to your behavior. We can’t see traits. Behavior is all we see when we watch an entrepreneur interacting with their environment. We spend a lot of time discussing this particular area in our program. Any kind of person can be a great entrepreneur if they discover an opportunity that enables them to play to their personal core strengths and talents. We teach students to really explore the world in a critical way, which they can do much more effectively after they have explored their true selves.”

2. Purpose can be part of the plan

Personal interests and passions are no longer relegated to off-hours; in fact, they can be the driving force to get people to step outside of their comfort zones and launch a new venture, Murphy says. As a researcher, he has an interest in social enterprise. (In 2021, his 2009 paper, “A Model of Social Entrepreneurial Discovery,” was ranked No. 6 in a list of the 100 most influential papers in that field.)

Expanding social enterprises in Alabama

Murphy notes that, in 2021, Alabama passed a benefit corporation law, making it the 38th state to create this new kind of business entity, which helps bridge the gap between for-profit businesses and nonprofit organizations. “It enables entrepreneurs to form a legal entity that is more aligned with social enterprise,” Murphy said. “It’s different from a 501(c)(3). You still need a board, and you get tax advantages; but you can also raise investment capital and generate returns.” Learn more in this blog post that Murphy wrote with Birmingham attorney Jonathan Murphy.

“Social entrepreneurs often focus on a triple bottom line: profit, planet and people,” Murphy said. “Mainstream entrepreneurs focus more on profit alone. But a social entrepreneur has a larger scope. They are interested in the economics, but they measure other outcomes too. It can be almost anything that is good for society — the education rates of young people, reductions in polluting emissions, crime rates in a community, number of people helped and more. Whatever the denomination of social value, it should be objectively measurable, and able to be correlated with accounting data, like revenue.

“We have a required class in social and community enterprise as part of our major, and students are strongly attracted to it,” Murphy continued. “Many future entrepreneurs want to do well and do good at the same time. They don’t see meaningful work as something different from making money. It’s not a tradeoff between working on Wall Street or working in a soup kitchen. Their career modes are becoming integrated, and I think technology has a lot to do with that. Social enterprises tend to be enabled by radically innovative technologies.”

Students present a project at the 2021 Blazer Hatchery and Hackathon event. See all the presentations here.

Students present a project at the 2021 Blazer Hatchery and Hackathon event. See all the presentations here.3. Differentiating uncertainty and risk is key

There is risk inherent in any venture, Murphy says, but risk and uncertainty are different in important ways. “Uncertainty is when you don’t know what you don’t know,” he said. “You don’t even know what questions to ask. By contrast, with risk, you know the possible outcomes; but you don’t know which one of those outcomes will occur. When one understands the nature of uncertainty, one can work to transform it into risk if one has a strong entrepreneurial mindset.”

Murphy likes to demonstrate this to his classes with a wager. “Sometimes I bet them $100 that two or more people in the class will share a birthday,” he said. “I say this with no knowledge of what their birthdays are, and it can seem like a risky proposition. There are always many students willing to take the bet. But I know enough about probability to know that it’s not risky. In a group of 40 or more, there is over a 90 percent chance that two people will have been born on the same day. It’s a simple piece of knowledge that most people don’t have, and with it, I know my bet is not much of a risk even if others see it as very risky. Knowledge works like that. Entrepreneurs need knowledge that shifts the risk. Of course, there is always the chance they may have bad knowledge or bad information, or that things might not work out; but what looks risky is often not, and it gives an entrepreneur the boldness to act. The principle applies to all kinds of people.”

4. How to translate problems into opportunities

“All entrepreneurship begins with problems, followed by attempts to resolve or fix them,” Murphy said. “We teach entrepreneurship students the value of a strong problem-solving orientation — the ability to be inspired by big unanswered questions, not big unquestioned answers. An orientation that purposefully seeks problems can take one out of one’s comfort zone. After all, it is human nature to seek stability and comfort. But for the purposes of one’s entrepreneurial work and vocation, there is great value in being attracted to problems and inefficiencies and finding constructive and creative approaches to resolving them.”

Entrepreneurs don’t see problems as others do, Murphy notes. “You need to redefine what a problem is,” he said. “The way we teach it in our program is to change the very definition. I lived in China as a young person, and I speak the Mandarin Chinese language. In that language, the word for ‘problem’ (问题) is the same word used for ‘question.’ The difference is in the context in which you use it. Questions call for answers, just as problems call for solutions.”

Murphy and his students explain what sets the entrepreneurship program apart in this video.

Murphy and his students explain what sets the entrepreneurship program apart in this video.5. Where to find your superpowers

Entrepreneurs are curious about the world. They are interested in how things work and what aspects of things are amenable to improvements. Curiosity is one of several “entrepreneurial superpowers” that UAB’s program develops in students, Murphy said, along with:

- coachability

- respect for mentors

- strong listening ability

- comfort with uncertainty

- clear set of personal values

- not caring too much what others think

6. How to reframe failure

“It is vital to separate ideas from people in entrepreneurial situations,” Murphy said. “Don’t let the person who is the source of an idea sway your thinking about an idea. Good people can have bad ideas. Bad people can have good ideas.

“Entrepreneurial teams need to clash with one another as a simple matter of brainstorming and problem-solving,” Murphy said. “It’s important to be kind to others, but it is just as important not to interpret critical feedback in a personal way. World-class entrepreneurial teams clash in healthy and intense ways. But it’s all about the ideas, not about the individual people on the teams. Students experience lots of intense team outreach projects in our program, and we emphasize this kind of discipline. It is basic human nature to conflate people and ideas, and it is very easy to take criticism personally. We want our entrepreneurship students to achieve the discipline to separate people and ideas in order to promote sharper and smarter entrepreneurial thinking.

“We also use this concept to reframe how our students think about failure,” Murphy said. “When an idea is bad, it does not mean a person is bad. Embrace this worldview, and it makes it easier to fail 90 percent of the time as an entrepreneur before finally making one winning attempt. The positive value of one success usually outweighs the negative value of nine failures, and one sometimes has to fail several times in order to succeed just once. One learns from the pattern of experiences.”

7. How to start strong — and prepare to branch out on your own

“People sometimes believe we are expecting our graduates to launch ventures right away,” Murphy said. “But in fact, we only expect a small number of them to do that. Over 90% of new jobs come from the entrepreneurial sector. What we actually expect is for our alumni to join entrepreneurial ventures and be able to add value right away. Many of these students will have connected with such ventures in our program’s outreach practice.

“Entrepreneurial ventures, unlike more established companies, need to hire talent that is ready to contribute on day one. They can’t afford to wait 10 months for a new hire to get up to speed. But these new hires are also future entrepreneurs. Most of the successful entrepreneurs I know worked for another entrepreneur for a while before branching out on their own. It’s a great steppingstone to becoming an entrepreneur. Our program prepares students for this path. It’s also how we make an impact on our regional entrepreneurial ecosystem.”