Lancer Smith and Alexandra Hillman are recent graduates of the master's program in health physics in the School of Health Professions. Both were hired at UAB after graduation. Grads with health physics training are “in really high demand,” said program director Emily Caffrey, Ph.D. Photos by Jennifer Alsabrook-Turner, UAB Marketing and Communications

Lancer Smith and Alexandra Hillman are recent graduates of the master's program in health physics in the School of Health Professions. Both were hired at UAB after graduation. Grads with health physics training are “in really high demand,” said program director Emily Caffrey, Ph.D. Photos by Jennifer Alsabrook-Turner, UAB Marketing and Communications

When Emily Caffrey, Ph.D., CHP, talks to students about health physics, she usually leads with this: No two days are alike. “I don’t like to be bored,” said Caffrey, assistant professor in the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences and program director for the UAB master’s program in health physics. “One day you may be in an abandoned uranium mine in a remote part of New Mexico; the next you will be somewhere totally different. Some weird scenario with radiation is always going to come up.”

The next thing she tells students: “It’s in really high demand,” Caffrey said. “There aren’t enough of us. There are 50 new jobs a month being posted. We’re one of the largest programs in the country, and we’re taking 15 students per year. Most of our students have multiple job offers prior to graduation.”

That leads to the next draw: “When something is in high demand, the salary goes up along with it,” Caffrey said. “You can make $80,000 to $100,000 per year with no experience and a master’s degree.”

Why come to UAB’s program? As Caffrey’s mention of its size indicated, this is one of the country’s leading training grounds. “We’re a quick program, too,” Caffrey said. “A year and one semester.”

What is health physics?

What exactly does a health physics graduate do? “We keep people and the environment safe from the harmful effects of radiation,” said Charles Wilson, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences, who has been interim program director while Caffrey has been in Washington, D.C., for a year in a Glenn T. Seaborg Congressional Science and Engineering Fellowship for the American Nuclear Society. (Caffrey has been working on nuclear policy on the Senate Budget Committee under Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island.)

Emily Caffrey, Ph.D.“Health physics isn’t a physics program,” Caffrey added. “We incorporate biology, chemistry, risk communications and psychology,” and the program has a history of bringing in successful students from a range of backgrounds, including a former theater major and, yes, some undergrad physics majors.

Emily Caffrey, Ph.D.“Health physics isn’t a physics program,” Caffrey added. “We incorporate biology, chemistry, risk communications and psychology,” and the program has a history of bringing in successful students from a range of backgrounds, including a former theater major and, yes, some undergrad physics majors.

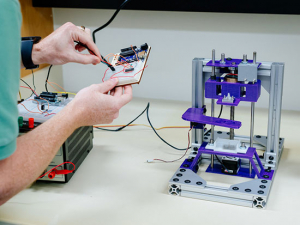

Program alumni at UAB weigh in

UAB Health Physics Assistant Alexandra Hillman discovered the program “after a lot of research and thinking,” she said. “I had no idea what health physics was,” Hillman explained, “but I knew I wanted to help people, and I knew I wanted to pursue my degree at UAB.” Health physics fit the bill, and after graduating from the master’s program in April 2023, she landed a job with UAB. Her main responsibilities include performing laboratory radiation safety audits, patient surveys, instrument calibrations and auditing reports. “I like that this role allows me to keep learning,” she said. It also gives her the chance to see how health physics is integrated into jobs across the campus and hospital settings.

Hillman’s colleague Health Physics Lead Lancer Smith also is a graduate of the master’s program. He was already working in the health physics field before he decided to go back to school to advance his career in the field. Having just moved to Alabama, Smith researched UAB’s program and was immediately drawn to the flexibility it offered, with courses available online as well as in class. “It worked with my situation, having a full-time job and a family,” Smith said. “There is no way I could have done it if I had to be in class in person every day. I would either have had to skip the program or quit my job. I have had people ask me about that, if it’s a tough program; I say, it is a time commitment and hard work, but you can also make it work for you.”

Another benefit of the program is “the ability to make connections,” Smith said. “They put us in front of people regularly — we attended the Health Physics Society meeting as a cohort, for instance — so you get a good feel for what is going on and the types of opportunities out there.”

Hillman agreed. “I loved that the professors were so open and honest about what this field was about and the things we would encounter,” she said. The supervised practice internships also gave her a chance to explore the possibilities of the field, Hillman added: “It was fun being able to learn how health physics plays into things we sometimes don’t think about.”

Smith says he enjoys the fact that health physics really comes down to problem-solving. “We work with people all over campus,” he said. “Much of the health side is standardized; but with researchers, you never know what the use case may be. You have to learn quickly what they are doing and then apply the radiation safety principles of time, distance and shielding to the situation. There is a lot of mental calculation and problem-solving to get to a system that will work for safety but also for the researcher’s needs. The interesting part is creating the process that covers all the bases.”

Emily Caffrey explains the effects of 5G radiation in this video from the Health Physics Society.

“I took a health physics class … and that was it”

Charles Wilson, Ph.D.Wilson was working for an ear, nose and throat practice during college, planning on going to medical school, when the practice’s doctors talked him out of that. One day, however, a computed tomography (CT) machine representative came in to deliver the practice’s repaired hardware. To prove that it had been fixed safely, “she took an image of herself and then told everyone she was pregnant,” Wilson said. “The physicians were really upset — you get a good dose of radiation with a CT and she had failed to balance the benefit and the risk. That’s how I learned about radiation safety; I took a health physics class after that, and that was it.”

Charles Wilson, Ph.D.Wilson was working for an ear, nose and throat practice during college, planning on going to medical school, when the practice’s doctors talked him out of that. One day, however, a computed tomography (CT) machine representative came in to deliver the practice’s repaired hardware. To prove that it had been fixed safely, “she took an image of herself and then told everyone she was pregnant,” Wilson said. “The physicians were really upset — you get a good dose of radiation with a CT and she had failed to balance the benefit and the risk. That’s how I learned about radiation safety; I took a health physics class after that, and that was it.”

Caffrey was a business major who switched to nuclear engineering as an undergraduate. She loved the science but not the engineering and swapped to health physics for her master’s degree and doctorate.

One reason for the growing need for health physics personnel is rapid growth in the medical industry around radiotherapy, along with decommissioning of older nuclear power plants and the development of new designs to produce clean energy in response to climate change. The atrophy in the nuclear power industry following the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl disasters means that the current workforce is being wiped out by retirements. “For every three people retiring, only one is coming into the field,” Wilson said.

That trajectory made it impossible for many university health physics programs to continue. UAB’s program saw the forecasted demand for the niche expertise and launched a new M.S. in health physics program in fall of 2016. Kathy Nugent, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences in the School of Health Professions, has consistently provided necessary support for the program, understanding the lack of a next generation to take over, Caffrey says. “We will always be a niche program, because it takes one-on-one training,” she said. “But we want to meet this national need here at UAB, and we want to do it well.”

In summer 2024, the program was approved to add an online delivery option, and a Ph.D. program aims to launch in fall 2026. “For most jobs, a master’s degree is the right level of education,” Caffrey said. “We have an internship program in our master’s, where students get three to six months of experience. You don't necessarily need a Ph.D. to get a good job, but there is a lot of cool research and other options you can do with it.”