Do the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas unwittingly produce a signal that aids their own demise in Type 1 diabetes?

Do the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas unwittingly produce a signal that aids their own demise in Type 1 diabetes?

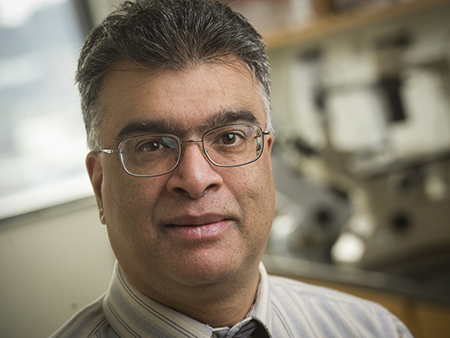

That appears to be the case, according to lipid signaling research co-led by Sasanka Ramanadham, Ph.D., professor of cell, developmental and integrative biology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Charles Chalfant, Ph.D., professor of cell biology, Microbiology and molecular biology, University of South Florida.

The research studied the signals that drive macrophage cells in the body to two different phenotypes of activated immune cells. The M1 type attacks infections by phagocytosis, and by the secretion of signals that increase inflammation and molecules that kill microbes. The M2 type acts to resolve inflammation and repair damaged tissues.

Autoimmune diseases result from sustained inflammation, where immune cells attack one’s own body. In Type 1 diabetes, macrophages and T cells infiltrate the pancreas and attack beta cells. As they die, insulin production drops or vanishes.

UAB researcher Ramanadham has spent decades studying lipid signaling in Type 1 diabetes. At South Florida, Chalfant studies lipid signaling in cancer, and his lab provides mass spectrometry expertise for both studies. Mass spectrometry is a very sensitive approach to identify different classes of lipids and quantify the abundances of such lipids.

The researchers focused on a particular enzyme, called Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2beta, or iPLA2beta. This enzyme hydrolyzes membrane glycerophospholipids in the cell membrane to release a fatty acid and a lysophospholipid, which by themselves can modulate cellular responses. Other enzymes can then convert those fatty acids into bioactive lipids, which the Ramanadham lab has designated as iPLA2beta-derived lipids, or iDLs. The iDLs can be either pro-inflammatory lipids that promote the M1 macrophage phenotype or pro-resolving lipids that promote the M2 macrophage phenotype, depending on which pathways are most active. Furthermore, the iDLs are released by the cell, so they could participate in cell-to-cell signaling.

|

"We think lipids generated by beta cells and immune cells are critical contributors to beta-cell death, leading to Type 1 diabetes.” |

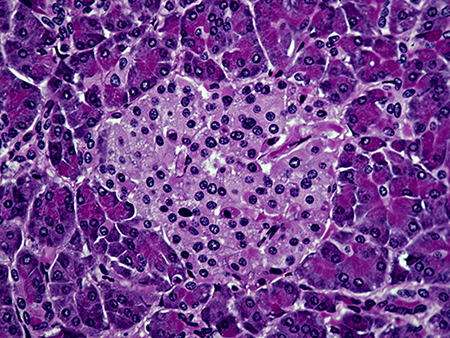

Beta cells and macrophages express iPLA2-beta activity.

To look at how the abundances of iDLs could affect inflammation, the researchers studied iPLA2beta-knockout mice and mice with beta cells in the pancreas engineered to overexpress iPLA2beta.

Macrophages from the iPLA2beta-knockout mice were isolated and then classically activated to induce the M1 phenotype. The researchers then measured the iDL eicosanoids produced by the macrophages that lacked iPLA2beta. Compared to wild type activated macrophages, the knockout macrophages produced less pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and more of a specialized pro-resolving lipid mediator called resolvin D2. Both changes were consistent with polarization to the M2 phenotype, a reduced inflammatory state.

Conversely, macrophages from the mice with beta cells that overexpressed iPLA2beta showed increased production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and reduced resolvin D2, as compared to wild type mice, reflecting an enhanced inflammatory state and polarization to the M1 phenotype.

“These findings, for the first time, reveal an association between selective changes in eicosanoids and specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators with macrophage polarization and, further, that the relevant lipid species are modulated by iPLA2beta activity,” Ramanadham said. “Most importantly, our findings unveil the possibility that events triggered in beta cells can modulate macrophage — and likely other islet-infiltrating immune cell — responses.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of lipid signaling generated by beta cells having an impact on an immune cell that elicits inflammatory consequences,” he said. “We think lipids generated by beta cells can cause the cells’ own death.”

Sasanka Ramanadham, Ph.D.Furthermore, “while the major focus of Type 1 diabetes studies is on deciphering the immunology components of the disease process, our studies bring to the forefront other equally important factors, such as locally generated lipid-signaling, that should be considered in the search for effective strategies to prevent or delay the onset and progression of Type 1 diabetes.”

Sasanka Ramanadham, Ph.D.Furthermore, “while the major focus of Type 1 diabetes studies is on deciphering the immunology components of the disease process, our studies bring to the forefront other equally important factors, such as locally generated lipid-signaling, that should be considered in the search for effective strategies to prevent or delay the onset and progression of Type 1 diabetes.”

Co-first authors of the Journal of Lipid Research study, “Macrophage polarization is linked to Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2beta-derived lipids and cross-cell signaling in mice,” are Alexander J. Nelson, UAB Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology and the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center; and Daniel J. Stephenson, Department of Cell Biology, Microbiology and Molecular Biology, University of South Florida.

Other co-authors, along with Ramanadham and Chalfant, are Christopher L. Cardona and Margaret A. Park, University of South Florida; Xiaoyong Lei, Abdulaziz Almutairi, Tayleur D. White and Ying G. Tusing, UAB Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology; and Suzanne E. Barbour, University of North Carolina.

Support came from the UAB Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology; the Iacocca Family Foundation; the King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Veterans Administration grants BX001792 and 13F-RCS-002; National Institutes of Health grants DK69455, DK110292 Diversity Research Supplement, HL125353, HD087198, RR031535 and AI139072; and University of South Florida funds initiative 0131845.

Ramanadham is a senior scientist in the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center.