Media contact: Beena Thannickal

At UAB, "precision medicine is our standard of care," says oncologist Eddy Yang, M.D., Ph.D.The tumor is in the salivary gland, and it’s a tough one. All the typical treatments thrown at it have failed. With nothing left to try, the patient’s doctor turns to a pioneering new kind of cancer program at UAB: the Molecular Tumor Board.

At UAB, "precision medicine is our standard of care," says oncologist Eddy Yang, M.D., Ph.D.The tumor is in the salivary gland, and it’s a tough one. All the typical treatments thrown at it have failed. With nothing left to try, the patient’s doctor turns to a pioneering new kind of cancer program at UAB: the Molecular Tumor Board.The MTB, led by Eddy Yang, M.D., Ph.D., launched in 2013. It was funded by UAB Hospital and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama to pay for gene sequencing in difficult cases like these. Sequencing can cost $4,000 or more, and because there is little available research on efficacy, insurers don’t usually cover it. But Blue Cross and UAB Hospital, like nearly everyone else in health care, appreciate the potential of gene sequencing in patient care. It’s up to groundbreaking programs like Yang’s MTB to help set the standard for how sequencing becomes part of standard practice.

A hit

The doctors send a small sliver of tumor to a specialized lab in St. Louis, where scientists look for mutations in more than 100 cancer-associated genes. A few weeks later, Yang has a hit.The patient’s tumor turns out to be driven by a mutation in the BRAF gene. BRAF makes a protein, B-Raf, that signals cells to grow. That means the tumor cells are overproducing B-Raf and turbocharging their growth rate. This is actually good news. The doctors have drugs that block BRAF — they’re used to treat the skin cancer melanoma. So the MTB recommends a combination of BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors, a related therapy.

“The cancer responded pretty well,” recalls Yang, who is ROAR Southeast Cancer Foundation Endowed Chair in Radiation Oncology, professor and vice chairman for translational science in the Department of Radiation Oncology and, program co-leader for Experimental Therapeutics at the O'Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB, and deputy director of the UAB Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute and its associate director for precision oncology. “The patient was in remission for more than a year.”

Precision oncology

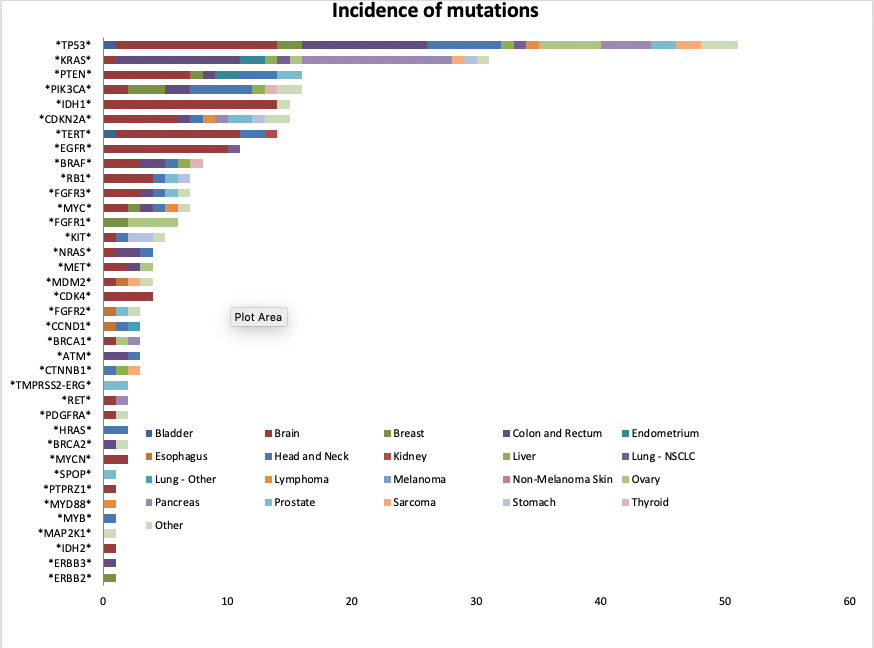

Cancer is a disease with a thousand faces. Oncologists like Eddy Yang have to recognize which one they’re seeing with each new patient. In the last few years, the job has gotten both easier and harder. There are now hundreds of drugs available to treat cancer — as well as new tools like gene sequencing to help doctors find the most appropriate treatment for each patient.But these tools have also demonstrated that cancer comes in many more varieties than the 100 or so named types, which are generally labeled by the organ where they are found. There isn’t just “breast cancer” or “uterine cancer,” for instance — there’s breast cancer driven by a BRCA2 mutation, and uterine cancer driven by a KRAS mutation. In May 2017, the FDA approved the drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) to treat metastatic solid tumors with microsatellite instability — the first time any regulatory agency approved a drug based on a molecular target rather than a specific tissue type.

“The goal of precision oncology is not to think about cancer according to its type, but as a cancer with a specific defect or driver,” such as a BRAF mutation, says Yang. In an intriguing new paper, Yang and colleagues report on three years worth of data from the MTB. It provides a glimpse into the future of medicine.

“Better treatment options”

During that three-year window, 191 cases were discussed at the MTB, and 132 cases were approved for testing. Out of 124 cases with results available:- 46 patients had predictive or prognostic mutations.

- The most common mutation site was the tumor suppressor gene TP53.

- 56 patients had mutations reported in cancer (but with no current predictive or prognostic significance).

- The number of mutations present in those two groups ranged from 1–6.

- 22 patients had no clinically significant mutations.

The results make clear that “sequencing isn’t a magical cure at this point,” Yang says. “We’re not going to find drugs for every person whose tumor we sequence.” Some mutations aren’t targeted by any current drugs, or may require a combination of treatments that hasn’t been identified yet. But the MTB experience, Yang says, demonstrates that “we may be able to offer better treatment options for some patients.”

New opportunities at UAB

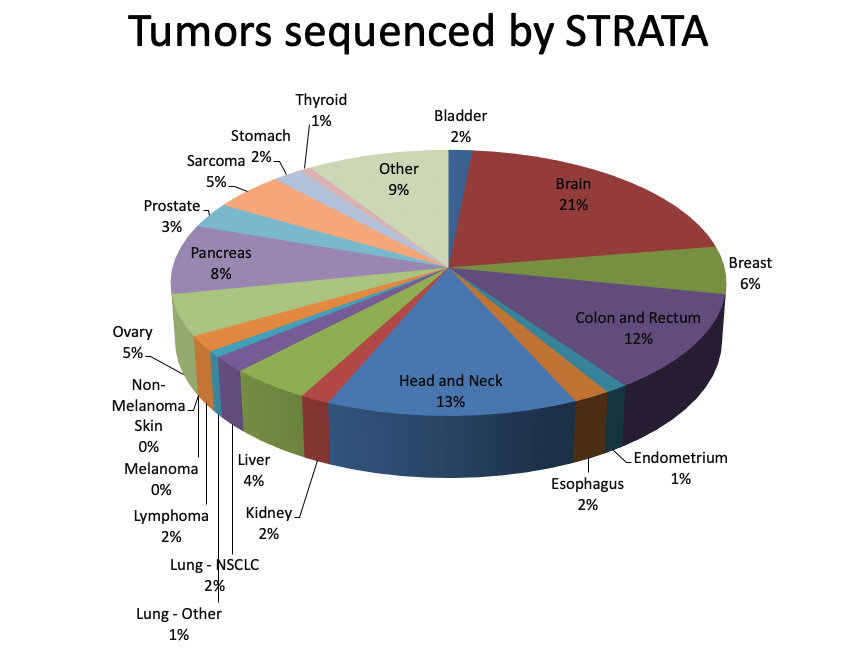

More patients have the option to receive sequencing, at no cost, thanks to UAB’s participation in the Strata Trial. Patients with metastatic or unresectable tumors, glioblastoma multiforme or pancreatic cancer, or a rare cancer are eligible to participate in the trial. Tumors are sequenced at no cost, with doctors selecting the most appropriate therapy based on the results. Another UAB-affiliated study, the TAPUR trial run by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, gives patients access to more than a dozen new targeted therapies.More than 300 patients at UAB have been sequenced as part of the Strata Trial. “We are now sequencing 50–60 patients per month,” Yang says. At this point, the “hit rate” — patients who have an actionable mutation — is around 70 percent. Of those, around 20 percent will get an offlabel drug or be enrolled in a clinical trial of a new drug, Yang notes. For a sizable number, sequencing lets doctors “know what drugs not to give,” he adds. For instance, patients with colon cancer are often treated with the drug cetuximab. “But if you have a KRAS mutation, we don’t use cetuximab,” Yang says.

The new standard of care

For patients with lung cancer, melanoma and colorectal cancer, the value of genetic sequencing for stage IV tumors upfront has already been demonstrated, Yang says. Insurance companies cover testing costs, and doctors specializing in these conditions now routinely order sequencing.“That’s the beauty of trials like Strata,” Yang explains. “For lung and colon cancer, ordering sequencing is now almost reflexive for doctors. Now at UAB, we can be reflexive for other types of cancer as well. Precision medicine is our standard of care.”