Media contact: Beena Thannickal

Gabrielle RocqueEvery cancer treatment, whether it’s an experimental drug or a trusted standby, comes at a cost. There is the literal cost, in dollars. “But schedules, toxicities, the burden on a family or other caregivers,” are all part of the equation as well, says Gabrielle Rocque, M.D., an assistant professor in the UAB School of Medicine Division of Hematology and Oncology and UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Gabrielle RocqueEvery cancer treatment, whether it’s an experimental drug or a trusted standby, comes at a cost. There is the literal cost, in dollars. “But schedules, toxicities, the burden on a family or other caregivers,” are all part of the equation as well, says Gabrielle Rocque, M.D., an assistant professor in the UAB School of Medicine Division of Hematology and Oncology and UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center.

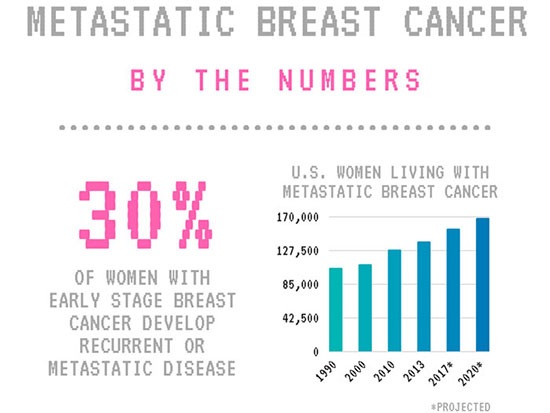

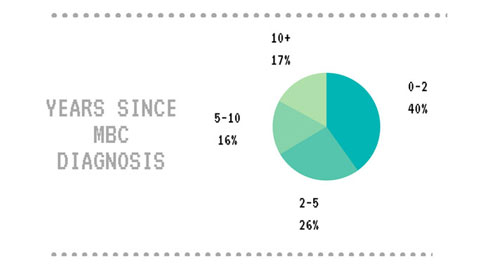

Rocque specializes in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Thirty percent of women with early stage breast cancer develop recurrent or metastatic disease, when the cancer has spread to other organs and is much more complicated to treat (typically because it has become resistant to the first-line treatments). More than 150,000 women in the United States are now living with metastatic breast cancer. Every year, more than 40,000 will die from the disease, but the median survival is now more than two years.

“That number continues to increase as new treatment options become available,” Rocque says. (See Game-changing therapies.) The growing number of therapies make treatment of metastatic breast cancer very complex. “There are different options for what you can do at any given time,” Rocque says. And each has its own schedule of required clinic visits, follow ups and side effects, she adds. “For patients with a limited life expectancy, hours spent in hospitals and clinics may cost them valuable time with their loved ones.”

In two new studies, Rocque is examining how to give patients a more informed role in those treatment decisions.

In two new studies, Rocque is examining how to give patients a more informed role in those treatment decisions.

With a grant from the American Cancer Society (ACS), Rocque is piloting a new model for shared decision making in metastatic breast cancer using treatment plans. These are documents, written in lay language, that provide patients with a game plan for their care. “Treatment plans have not been tested in metastatic cancer, where they may provide the greatest benefit,” Rocque noted in her grant application.

As part of its participation in the Oncology Care Model program from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, UAB is already using software called Carevive to give patients treatment plans once treatment begins. With her ACS study, Rocque is testing what happens when patients have input before the plan is set. To begin, she and her team are interviewing patients, patient navigators, nurses and physicians at UAB to gather a picture of the most important topics to consider, including personal and treatment goals, along with concerns such as being a burden to others.

“These are patients who are going to be on treatment for the rest of their lives,” says Rocque. “It’s important to consider both quantity and quality of life.”

Rocque will use information from these patient interviews to create an electronic treatment planning tool, then test it in a randomized controlled trial against the current standard of care. Follow-up surveys will examine how the treatment plans affect patients’ experience of shared decision making in their care.

Previous studies of treatment plans in other diseases have found that both patients and their providers appreciate having these tools available. But the costs of implementing treatment plans are an important factor in adoption as well, Rocque notes. “Any change has to work for all participants in the health-care system, including patients, providers and payers, such as insurance companies,” she says. “Otherwise it’s not sustainable.” So Rocque is also conducting an economic analysis as part of her study. New Medicare rules are tying doctor’s payments to a number of metrics, including patients’ rating of shared decision making. Rocque’s analysis will examine whether the costs of software and time involved in treatment planning will be outweighed by improved payments from Medicare and other payers.

Previous studies of treatment plans in other diseases have found that both patients and their providers appreciate having these tools available. But the costs of implementing treatment plans are an important factor in adoption as well, Rocque notes. “Any change has to work for all participants in the health-care system, including patients, providers and payers, such as insurance companies,” she says. “Otherwise it’s not sustainable.” So Rocque is also conducting an economic analysis as part of her study. New Medicare rules are tying doctor’s payments to a number of metrics, including patients’ rating of shared decision making. Rocque’s analysis will examine whether the costs of software and time involved in treatment planning will be outweighed by improved payments from Medicare and other payers.

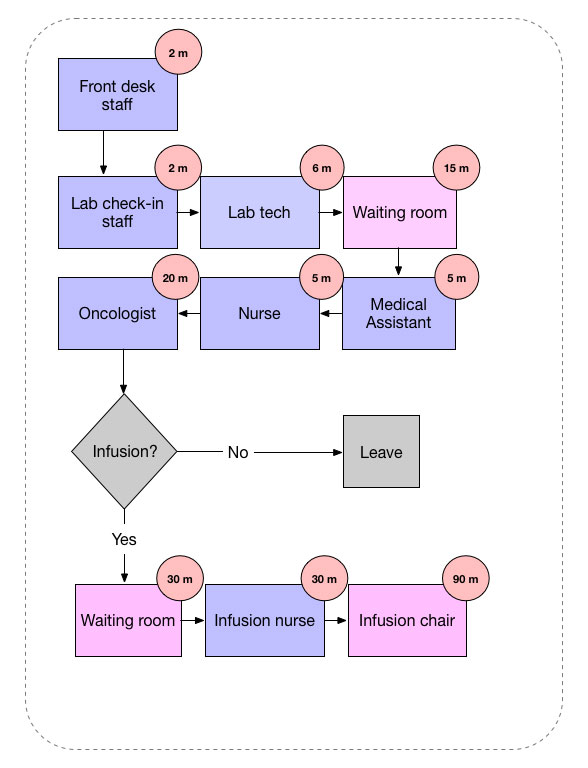

The entire national debate about health-care revolves around financial costs. But surprisingly little is known about the true costs of metastatic breast cancer care, in money and time, Rocque says. She is looking to fill that gap with an unprecedented analysis — a combination of Medicare and private claims data, patient surveys, and a process known as time-driven activity-based costing, which charts how long each step takes in a clinic visit, from the wait at reception to the consultation with the oncologist and any treatment infusions.

“We’re tracking anything that a patient is doing related to health-care that is taking up time,” says Rocque. “That includes the time it takes to drive to appointments, going to pick up prescriptions, talking to staff on the phone to set up future visits.” By charting the staff time involved in each step of the treatment cycle, Rocque will also be able to quantify the true cost of treatment to a health system.

Hypothetical example of a time-driven activity-based costing process chart.

Hypothetical example of a time-driven activity-based costing process chart.

The study, funded by a grant from biotechnology company Genentech, will feed invaluable data to doctors that they can use to improve care, Rocque says. “We don’t talk to patients a lot about how much time and effort some of these treatments require,” she notes. “That’s because we don’t have a great idea of the magnitude of time involved.

“If someone is going on a clinical trial, we know that will take more time, but how much? It may be where we’ll be able to say, ‘There are two different treatments available: over the next six months, on one you’ll spend 20 hours in the clinic, and with the other, you’ll spend 150 hours in the clinic.’ That might be something patients really care about, and I’ve never seen people be able to quantify that. It won’t be perfect, but it will give them an idea.”

| Game-changing therapies: Guidelines from the National Cancer Care Network now list 45 different treatment options for metastatic breast cancer. “The first class that really revolutionized treatment were the HER–2 targeted therapies,” such as Herceptin, says Rocque, “followed by the CD4/6 inhibitors like palbociclib and ribociclib, which is doing similar things in the ER-positive space. These are classes that are really well targeted, but come at a really high sticker price.” back to story |