Jim McClintock, Ph.D.Marine life along the Gulf of Mexico is not doing well. Vast numbers of oysters, blue crabs, shrimp and fin fish off coastal Louisiana, Mississippi and bays of Alabama have been killed outright or driven from marshes. In Louisiana and Mississippi, the deathblow was an unprecedented outflow of fresh water juiced, among other sources, by the opening of the Louisiana Bonnet Carre Spillway that poured fresh water from an already swollen Mississippi River into Mississippi Sound.

Jim McClintock, Ph.D.Marine life along the Gulf of Mexico is not doing well. Vast numbers of oysters, blue crabs, shrimp and fin fish off coastal Louisiana, Mississippi and bays of Alabama have been killed outright or driven from marshes. In Louisiana and Mississippi, the deathblow was an unprecedented outflow of fresh water juiced, among other sources, by the opening of the Louisiana Bonnet Carre Spillway that poured fresh water from an already swollen Mississippi River into Mississippi Sound.

The resultant massive slug of coastal fresh water is ultimately the result of the record-breaking rainfall in the Midwest, boosted by climate change. Moreover, it is not just the states in proximity to the Mississippi River that are experiencing fresh water impacts. In Alabama, Andy Depaola, who owns and operates Depe Oysters, an oyster farm in Mobile Bay, reports that the salinity has been so low around Point Clear in Mobile Bay that losses of oysters may exceed the losses in Mississippi Sound.

The impacts of coastal fresh water go much deeper than the dramatic loss of oyster, shrimp and crabbing industries reported by Joe Spraggins, executive director of the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources. Hundreds of jobs in seafood harvesting and processing and their downstream impacts on family livelihoods are at risk.

Over the past several weeks, the governors of Louisiana and Mississippi have asked the federal government for Federal Fisheries Disaster Declarations to help offset losses. As if the loss of coastal fin- and shellfish were not enough, Moby Solangi, executive director of the Mississippi Institute for Marine Mammal Studies, reported 128 dolphins and 154 sea turtles have become likely victims of the big freshwater flush, many of their carcasses sporting fresh water lesions. Record losses of dolphins and sea turtles, both considered key indicators of the overall health of marine environments, speak not just to the human heart but also to the growing challenges of climate change to the sustainability of coastal ecosystems.

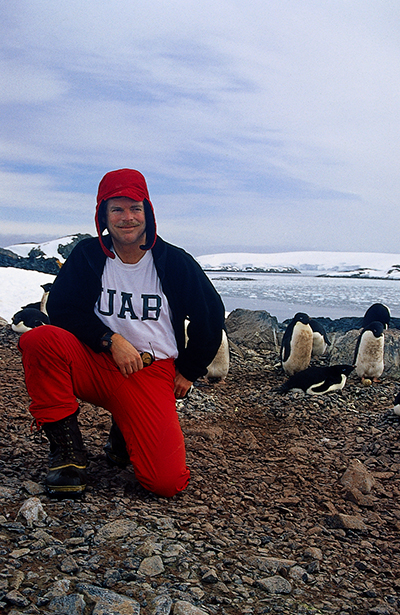

Even in the relatively conservative South, the days of speculating about the hypothetical impacts of climate change are largely over. No longer is the focus of climate change only on polar bears and penguins. Significant change has arrived in our backyards. In Alabama, record-breaking torrential rains are not only reducing salinity of coastal bays, but causing floodwaters that carve into river banks, turning waters muddy brown with gill-clogging sediment.

Gulf states are experiencing weather extremes: warmer temperatures that welcome tropical disease-bearing mosquitos, hotter days that may lead to heat strokes, longer periods of drought that dry out Southern forests and support unprecedented crown fires that spread from treetop to treetop, and more powerful hurricanes.

This past October, Hurricane Michael ripped through the Florida panhandle with wind speeds equivalent to an F5 tornado. The largely blue-collar town of Mexico Beach, Florida, resembled an apocalyptic wasteland when I drove down the main street a little over a month after the hurricane hit. Sadly, as the new hurricane season begins, the town remains largely in shambles.

Last week, I visited Washington, D.C., to meet with Alabama Senators Richard Shelby and Doug Jones to discuss conservation and climate change. While visiting, I learned that one of the most politically potent groups sharing their narrative of climate change on the Hill is The Shellfish Growers Climate Coalition. Made up of several hundred oyster fishers from shellfish industries along our Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts, their collective plea to reduce national carbon emissions is rooted in the need to mitigate the ocean acidification and warming that threaten their industry. Their voices are certain to be amplified as local and Midwest flooding rain continues to devastate the coastal fisheries of the northern Gulf of Mexico.