Student Carl Frizell (left) gains clinical experience with guidance from physician assistant Stephanie McGilvray (center).

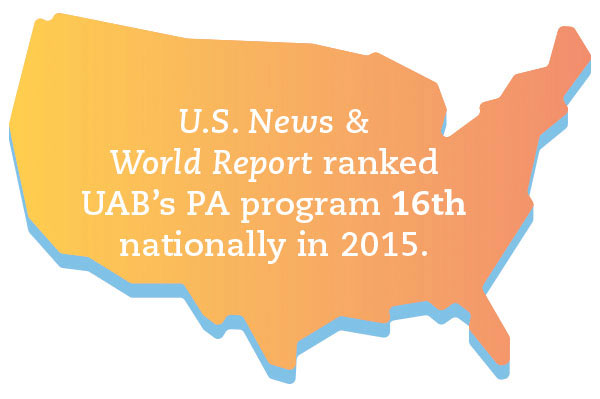

Student Carl Frizell (left) gains clinical experience with guidance from physician assistant Stephanie McGilvray (center).When you hold the keys to a hot career, don’t expect a slow summer. “For this fall, we have received more than 1,000 applicants for 90 slots,” says James R. Kilgore, Ph.D., PA-C, DFAAPA, director of the physician assistant program in the UAB School of Health Professions. Nationwide, universities with similar programs received approximately 23,000 applications for 6,500 openings, he says.

The boom corresponds with rising demand for physician assistants (PAs) as more people obtain health insurance. Clinics and hospitals across the country are adding the position to serve growing numbers of patients, and in underserved rural areas, practices are turning to PAs to help expand access to care. As a result, new graduates in the field often have their choice of positions and job security. UAB’s PA master’s program also plans to expand—with a goal of admitting 120 students by 2020—to help meet the need for more caregivers.

Extending opportunities

Extending opportunities

PAs “really are a physician extender; we are trained in the medical model,” Kilgore says. In fact, PA students share some common ground with medical students, he explains. Admission criteria are similar, as is their training, which includes didactic and clinical work in primary care, trauma, critical care, emergency medicine, and surgery, often in medical facilities throughout the region. “Many of the students entering our program could get into medical school,” Kilgore says.

So why don’t they? “Medical school debt is about $250,000 for four years, and it’s about $90,000 for two-and-a-half years for a PA degree,” Kilgore says. PAs also can earn a good salary as soon as they graduate, with less of the stress and expense of running a practice.

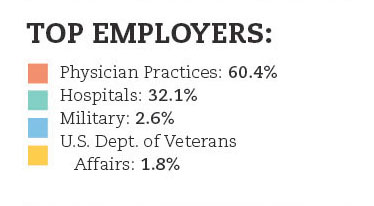

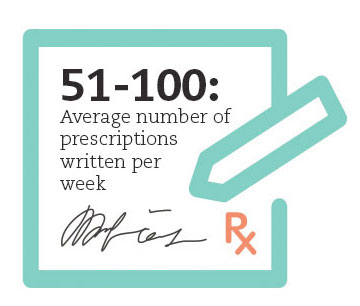

PAs see patients and assist in emergency rooms, operating rooms, and exam rooms; they work in all major specialties; and they have full prescribing rights in many states, including Alabama. They must work in a clinical setting alongside a physician, but the M.D. doesn’t have to be present all the time, which could make PAs an important asset in rural and underserved areas, Kilgore says.

“In Alabama, we have a significant access issue, with 62 of 67 counties either fully or partially underserved,” he explains. The problem has gotten worse as struggling rural hospitals have closed over the past decade or so. In those areas, PAs can help relieve physician workload by handling common care issues or follow-up appointments, for instance.

Bringing care back home

Bringing care back home

Convincing graduates to provide primary care in rural areas can be challenging when they have so many job options, Kilgore says. If they specialize or work in a city, then the new PAs often can make more money and sometimes have more predictable hours.

UAB is focusing on a new family practice/primary care specialty option to help address that issue. Only 22 percent of the more than 600 PAs in Alabama work in primary care, so the new training program could make a significant impact, Kilgore says. He also is seeking additional physicians in small towns to act as preceptors for PA students.

The faculty has been working hard to recruit rural students like Carl Frizell, who has become something of an ambassador for UAB’s PA program. Back in high school in Holmes County, Miss., Frizell had never heard of PAs. In fact, he had little exposure to medical professions because care providers are scarce. “A lot of the time, we have to travel at least an hour away to get decent services,” he says.

Frizell was pursuing a Ph.D. at UAB when stress and anxiety over his mother’s fight with cancer sent him to a UAB emergency room. There, he met a PA, Kara Caruthers, MSPAS, PA-C, who also serves on the PA program’s faculty as an assistant professor. Her caring manner, coupled with his mother’s advice to pursue a happy life, encouraged him to become a PA himself.

Now a senior, Frizell connects with high-school students via social media and mentors UAB undergraduates to help introduce younger people to health-care careers and degrees they might not have considered. Frizell, who recently won a prestigious scholarship from the national Physician Assistant Foundation, also plans to work in rural Alabama or Mississippi when he graduates. “It has become my passion to make sure we have adequate health-care resources,” he says.

Clinic to capital

Clinic to capital

Efforts by PAs to improve access to health care across Alabama don’t end at the clinic door. Some have taken political action to expand their roles, such as the right to prescribe scheduled medications, says Stephanie McGilvray, M.M.Sc., PA-C., assistant professor in UAB’s Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences, who took part through professional organizations. Recently, she became the only PA named to the Alabama Health Care Improvement Task Force, a group of 38 health leaders looking for ways to make care more accessible and more affordable.

McGilvray encourages her students to get involved so that PAs have a voice when decisions are made. One who heeded her advice is Brad Cantley, a Birmingham native and 2012 graduate now working in a family care/obstetrics clinic in Sylacauga, an underserved area, and a nearby emergency room. Before enrolling in the PA program, Cantley was a firefighter and emergency medical technician; today, he is president of the Alabama Society of Physician Assistants. He credits the PA program’s “exposure to a wide variety of surgical and medical training” for his success with both patients and politicians.

Written by UAB Magazine

Media contact: Adam Pope