Media contact: Anna Jones

When Emory Carter was diagnosed with myopia, he and his father saw this diagnosis as an opportunity to help others in the Black community by participating in myopia research.

When Emory Carter was diagnosed with myopia, he and his father saw this diagnosis as an opportunity to help others in the Black community by participating in myopia research.

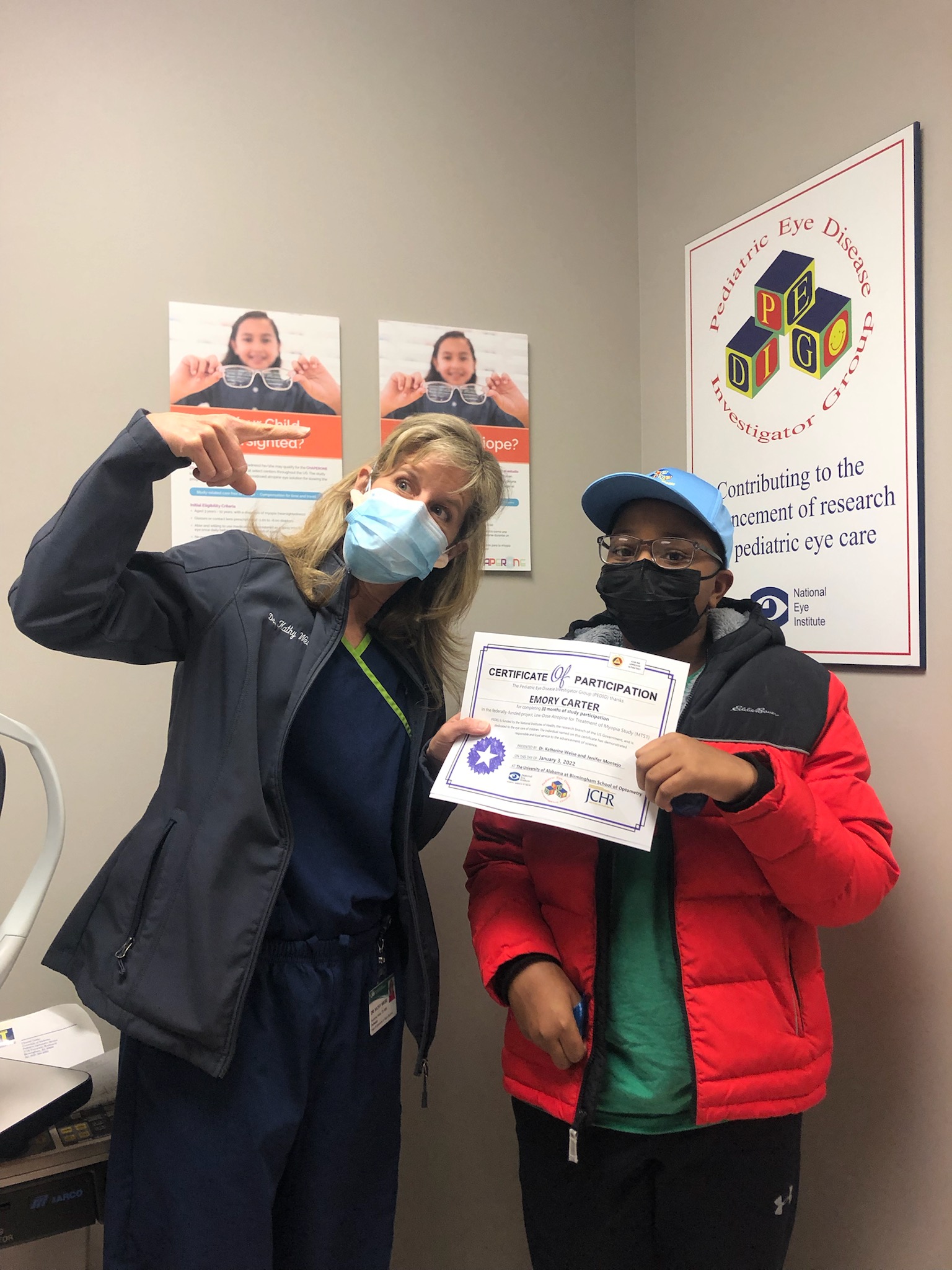

Photography: Jenifer Montejo, Research CoordinatorNo kid wants to be told they are nearsighted. Emory Carter was 8 years old when he was diagnosed with myopia, or nearsightedness. However, unlike many children his age, Emory saw his diagnosis as an opportunity, not an obstacle.

Emory’s father, Hernando Carter, M.D., assistant professor in the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Department of Medicine, knows firsthand that, despite having a disproportionate burden for certain diseases, racial and ethnic minorities like the Carters are frequently underrepresented in medical research. Emory and his father saw this diagnosis as a chance to help others in the Black community by participating in myopia research.

A routine eye exam identified Emory’s myopia, which occurs when the eyeball is too long or the cornea — the protective outer layer of your eye — is too curved. His optometrist encouraged Hernando and his son to consider participating in a clinical trial run by Katherine Weise, O.D., pediatric optometry service director at the UAB School of Optometry.

“Participation in clinical trials should reflect our diverse population,” Carter said. “In order for racial and ethnic minorities to benefit from research, they need to be involved in every stage of the research process. When Emory and I were told about the clinical trial, we discussed the importance of the trial and the impact it could have on the Black community; but I ultimately left the decision up to him.”

Emory, motivated by his love for science and his community, made the decision to participate. His father says Emory’s participation in this study was about becoming an example for others, especially in the Black community, given the history of mistrust in the health care system.

“My goal going into this study was helping find the treatment for myopia not just for my son, but for others like him,” Carter said.

Emory began participating in the 30-month study, taking low-dose atropine eye drops every night for 24 months, followed by six months of treatment. Throughout the duration of the study, Emory had to use the drops every night, fill out a calendar, wear his glasses and come to UAB Eye Care for appointments. His desire to help others locally and around the world motivated him to push through. As the trial progressed, Emory and his father developed an even stronger bond than they already had prior to the trial.

“It became something just he and I did. It became our thing,” Carter said. “I took him to every appointment, I helped him with his eye drops, and we talked about the impact he was making every night. It was important for the both of us that we did it together.”

Carter told Emory, who is now a fifth grader, how proud he was for completing this research study.

“When we finished up our last day of the trial, I just wanted Emory to know how proud I was of him,” Carter said. “It is so important for people like us to participate in this research, so that we can help others who look like us. It was just such an honor to get to walk with him through this process and see the difference he was making in his community.”

Diversity in Clinical Research

Ensuring people from diverse backgrounds join clinical trials is key to advancing health equity. Unfortunately, individuals from racial and ethnic minority and other diverse groups are typically underrepresented in clinical research. Through her research, Weise and her team hope to bridge that gap by including more diverse, underrepresented populations in her study. To date, 60 percent of local participants in Weise’s myopia study are underrepresented minorities.

“My research team and I are very passionate about including people from underrepresented groups in our research,” Weise said. “An inclusive study leads to more generalizable results; it means we know how our treatments work in more people. Without people like the Carters who persevered for 30 months and followed the research process perfectly, this study would not be possible, nor would it be a true representation of U.S. kids.”

Weise and her team’s nearsightedness research, called MTS1, is a federally funded, national multi-center randomized clinical trial that focuses on how atropine, a medication commonly used to dilate the pupils, can be used to slow down the growth of the eye, thus slowing myopia progression. There are studies with children living in Asia that demonstrate how effective atropine is at slowing down myopia progression, but Weise’s study is the only federally funded trial to focus on a diverse group of children in the United States.

“We hope this study builds on what we know about pharmacological interventions for myopia,” Weise said. “We know the higher concentrations slow down the growth of the eye, but higher concentrations are associated with more side effects. Through this study, we are trying to determine how diluted we can make the atropine drop to take advantage of the effectiveness of the treatment while minimizing side effects. If we can find evidence-based treatment options to slow down nearsightedness, like low-dose atropine, we can maximize the uncorrected vision of people who are nearsighted. Since 50 percent of the global population is expected to be nearsighted by 2050, this study has worldwide implications, and Emory is a big part of that.”

UAB Eye Care is one of the 14 sites in the United States funded by the National Institutes of Health devoted to studying myopia and has the only federal funding to conduct pediatric research to study the effects of low-dose atropine to treat nearsightedness. The study is still ongoing and will wrap up in the fall of 2022.

“Study participation requires responsibility, reliability, dedication to the greater good and a willingness to put others above oneself,” Weise said. “This father-son team had the same visions that we did back during the informed consent process 30 months ago, and we are so grateful for their time and participation in this research. I’m super proud to be Emory’s pal. He inspires me.”