Videography: Laura Gasque, Carson Young, Andrea Mabry

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was written pre-COVID-19. All patient care experiences mentioned in this article do not reflect the current care guidelines

Cooper Pierce was 13 years old when doctors diagnosed him with pulmonary hypertension. After undergoing a heart and double-lung transplant at UAB Hospital, he is now a student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and hopes his story can inspire others.

Pulmonary hypertension is a disorder in which blood flow from the right side of the heart faces increased pressure. Normally, blood flows from the right side of the heart into the pulmonary arteries and smaller blood vessels in the lungs. The blood vessels have muscles in their walls that can relax or contract to control the amount of blood that enters the lungs. In pulmonary hypertension, the blood vessels of the lungs have an increased amount of muscle in the walls, causing higher resistance to the outflow from the heart. The right side of the heart then has to work harder to pump blood out to the lungs. The right side of the heart will enlarge and thicken in response to this extra work. With time, the extra work placed on the right side of the heart can cause it to fail.

“The way I like to describe it to people is like really bad asthma,” Pierce said. “I used to play baseball, and if I hit the ball, by the time I got to first base it was like I was already out of breath and blue. Or, I would walk up a flight of stairs and I’d be blue and breathing really hard.”

Photography: Andrea MabryAfter receiving his diagnosis, Pierce felt relief just knowing the cause of his breathing problems.

Photography: Andrea MabryAfter receiving his diagnosis, Pierce felt relief just knowing the cause of his breathing problems.

“It brought some clarity,” he said. “I was actually kind of relieved about it.”

Although he had his diagnosis, Pierce did not let that obstacle get in the way of living as a normal teenager.

“I just went about it the same way any 13- through 17-year-old went about living,” he said. “I had this condition like really bad asthma, but I tried not to let it slow me down. I still played baseball for a little bit, and I still led a fairly active lifestyle. I had some moments along the way; but I went to a small school in a smaller town, and even the teachers were behind me. And you know if I acted out a little bit, they knew what was going on, and then they would give me some space and sit down and talk with me. So, it definitely added a bigger layer to being a teenager, but it was OK.”

When he was 16, Pierce — who was receiving care through Children’s of Alabama at the time — was referred to doctors at UAB Hospital. During his first visit, he was told that a transplant would be necessary.

“On my first visit, they just dropped it on me,” he said. “They told me that they were going to maybe consider a heart and lung transplant. They didn’t hold back, but I appreciate that kind of transparency.”

After nearly a year of waiting and tests, Pierce was told he would receive a heart and double-lung transplant.

“I was freaked out — do not get me wrong — but I definitely put on a brave face for my family and friends,” he said. “I would say, ‘It’s going to be fine’; but maybe I was telling myself that, too. I tried to just kind of take a step above and be strong for them.”

Pierce’s transplant was performed by Charles Hoopes, M.D., professor in the UAB Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery.

“Pulmonary hypertension is not common in people his age,” Hoopes said. “There are only about 40 heart and double-lung transplants performed a year; but because he was so young, we thought it would be best to go through with a transplant.”

After a nine-day stint in the hospital, Pierce felt an immediate difference in his breathing.

Photography: Andrea MabryBlazing ahead

Photography: Andrea MabryBlazing ahead

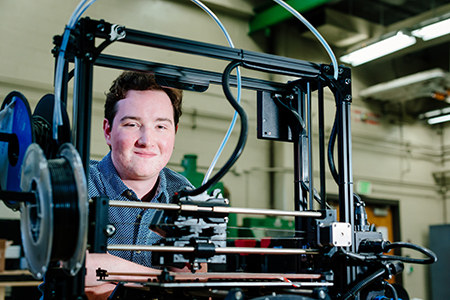

Pierce is a student at UAB with an undeclared major, but has always had an interest in engineering, specifically 3D printing — something he hopes to incorporate in his future.

“I’ve always enjoyed engineering things,” Pierce said. “I was 3D printing well before I had my transplant, and once I got my transplant, I saw that a lot of people were already printing organs for transplant. If I can be on the forefront of that or forefront of any additive manufacturing stuff, that would be awesome. If you 3D print organs with your own stem cells, cells of your own, there’s no chance of rejecting the organ. That’s the number one thing that somebody who has received a transplant is worrying about is the rejection. You have to take medicine every day —trust me, I know — and transplants would be a breeze if we didn’t have to worry as much about rejection at all.”

Pierce received his transplant before he came to college, but he always had UAB in the back of his mind as a place to further his education.

“The facilities at UAB are always nice, and I don’t live too far from here,” he said. “I could live at home. That was a big thing, because I had to commit to UAB before I got my transplant, and so it was close to home. I was at UAB getting and receiving my care, and I knew I wanted to do something in engineering, and they have a great engineering program.”

Organ donation

Organ donation

Pierce knows that he would not have received his lifesaving organs without the passing of someone else. It is something that constantly reminds him how fortunate he is, and while he has not had an opportunity to meet the family of the person who donated the organs, he says he will always be forever grateful.

“I hope people can find inspiration in my story,” he said. “I’m a best-case scenario. I wouldn’t be where I am without someone else’s sacrifice.”