Xavier Horton of Madison is the first person to get DBS for epilepsy.“I’m a cyborg. I’ve got a little CPU in my chest.”

Xavier Horton of Madison is the first person to get DBS for epilepsy.“I’m a cyborg. I’ve got a little CPU in my chest.”

Calling himself a cyborg may be a bit of a stretch. While Xavier Horton may not be the next villain (or hero) of a science fiction movie, he is the first person in Alabama to receive deep brain stimulation for epilepsy. That means he does have a small electrical stimulator implanted in his chest, and it does have a small central processing unit. Most importantly, it may be the tool that brings relief from the seizures that have plagued Horton since he was 12 years old.

Now 24, Horton, from Madison, Alabama, developed epileptic seizures in 2006. He went on medication, and underwent one surgery in an attempt to pinpoint the area of the brain responsible for his seizures. Unfortunately, the location of the abnormality could not be determined with sufficient accuracy, so surgical removal of that area was not an option.

That is where DBS, or deep brain stimulation, came in.

Horton’s neurology team at the University of Alabama at Birmingham first mentioned DBS in 2016 while it was still in the experimental stage. The procedure is best known for its use with Parkinson’s disease, approved for that condition in 1997. It has since become a treatment option for dystonia, essential tremor and drug-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. DBS was approved for epilepsy in 2018.

Neurosurgeons insert narrow electrodes into the brain, specifically into the anterior thalamic nucleus in both hemispheres. The electrodes are connected to a neurostimulator implanted in the chest, not unlike a pacemaker, by wires just beneath the skin.

“The neurostimulator supplies an electric current that disrupts the electrical activity responsible for triggering the seizures, basically interrupting a seizure before it can get started,” said Jerzy Szaflarski, M.D., Ph.D., director of the UAB Epilepsy Center and a professor in the Department of Neurology, School of Medicine. “The path of the electrical impulses that trigger seizures frequently passes through the anterior thalamic nucleus, so it’s the most appropriate target to intercept and modify those impulses via the current from the stimulator.”

Horton was the 27th person in the nation to receive DBS for epilepsy, on Feb. 22, 2019.

“We employ new techniques of magnetic resonance imaging for planning and precisely targeting the nucleus in our surgical approach,” said Nicole Bentley, M.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Neurosurgery who implanted the device in two separate procedures. “We then merge the MRI images with a CT scan done in the operating room to place the electrodes in the best location for maximum effect.”

“We employ new techniques of magnetic resonance imaging for planning and precisely targeting the nucleus in our surgical approach,” said Nicole Bentley, M.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Neurosurgery who implanted the device in two separate procedures. “We then merge the MRI images with a CT scan done in the operating room to place the electrodes in the best location for maximum effect.”

Horton has what is known as frontal lobe epilepsy, which leads to frontal onset seizures.

“These are small seizures, and I might have several a month,” Horton said. “They might last a few seconds, or last for more than a minute. I could be in the middle of a conversation and would space out. I’d be unable to talk or respond to people, while they wouldn’t be aware that I was having a seizure. I could see them looking at me, but I would not be able to respond. It was uncomfortable and awkward.”

It also made it hard to hold a job or drive a car, since Horton had no way of anticipating when a seizure might strike.

Following surgery to implant the electrodes in the brain and the stimulator in the chest, the system is turned on and fine-tuned.

A DBS lead is implanted into each of the brain’s two hemispheres. There are four contacts on each of the leads, and each contact can be modified in power and intensity. This allows for thousands of possible combinations to paint the most effective pattern of electrical activity for each patient to alleviate their seizures.

“We anticipate a reduction of seizures of 60-70 percent,” Szaflarski said. “If he has five a month, the DBS system might reduce that to just one per month. Adjustments in medication might also help reduce the frequency. There is evidence that the repeated application of the current over time could also reduce the number of seizures even more.”

DBS is not for every patient with epilepsy, but it is an important new option.

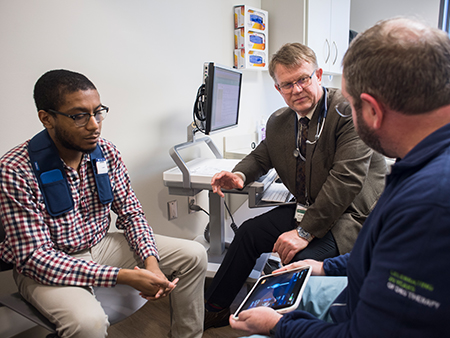

Horton observes the readout of his stimulator with Dr. Jerzy Szaflarski and Medtronic representative Michael Tapley.“It’s not a cure in most cases, but it is an option for treatment,” Bentley said. “Medication is the first treatment; but if those fail and seizures cannot be localized to one specific area, DBS surgery may be an option. For some patients, there are no other viable options.”

Horton observes the readout of his stimulator with Dr. Jerzy Szaflarski and Medtronic representative Michael Tapley.“It’s not a cure in most cases, but it is an option for treatment,” Bentley said. “Medication is the first treatment; but if those fail and seizures cannot be localized to one specific area, DBS surgery may be an option. For some patients, there are no other viable options.”

DBS is not the only technology that uses neurostimulation to treat epilepsy. VNS stimulates the vagus nerve in the neck and does not involve brain surgery. RNS uses leads implanted at the site of seizure onset, with the battery implanted in the top of the skull to produce electrical pulses when seizure activity is noted.

“DBS is the newest technique; but all of these are options, depending on the needs of the patient,” Szaflarski said.

It will take a few months for Horton to know just how well DBS is working for him. Along with his physicians, he will monitor the frequency and severity of his seizures over time. His initial reaction has been positive, and he feels as if the frequency of his seizures has lessened. That is good news for a young man with plans.

“I’ve had a lot of restrictions in the past, and there are a lot of things I want to do,” Horton said. “I’m hoping that DBS will allow me to start doing those things — get a job and a career, move out from my parents. This is a good start.”