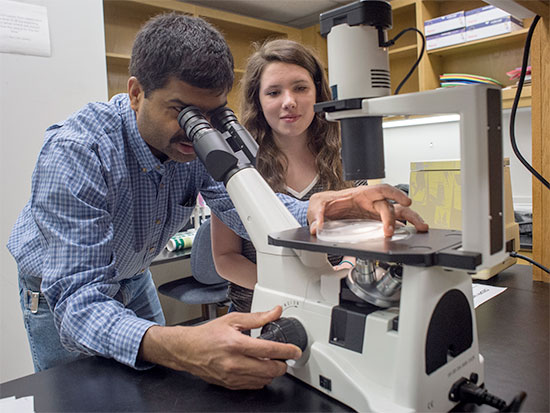

Cerissa Nowell’s petri dish, holding zebrafish embryos, is checked by Anil Challa.An exclamation erupted at one of the microscopes in a University of Alabama at Birmingham lab.

Cerissa Nowell’s petri dish, holding zebrafish embryos, is checked by Anil Challa.An exclamation erupted at one of the microscopes in a University of Alabama at Birmingham lab.

“Dr. Challa, oh my god, I’ve got one!” said sophomore biology major Reagan Andersen.

For the 16 freshman students from the UAB Honors College's Science and Technology Honors Program, their search for mutant zebrafish embryos that develop only a single eye was part of an authentic research experience lab course run by Anil Challa, Ph.D., this spring.

This cutting-edge approach pitches young college students into real research. Unlike cookbook lab courses with rote experiments, Challa’s course-based undergraduate experience — which uses the molecular genetic “scissors” CRISPR/Cas9 — asks questions to which the answers are not known.

It is part of a national undergraduate biology education reform effort. As the 2009 national conference report “Vision and Change – A Call to Action” says, such courses give undergraduates “an opportunity to experience the allure of the scholarship of research.”

“Hands-on research also cultivates scientific thinking, allowing students to experience authentic activities of working scientists,” the report says, “including designing studies, interpreting unexpected outcomes, coping with experiments that fail, considering alternative approaches, and testing new techniques — all activities that are difficult, if not impossible, to replicate in standard lecture or laboratory courses.”

Unexplored genes

“I like how Dr. Challa viewed everything in the perspective of a long experiment,” said Samantha “Sami” Foster, a neuroscience junior in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences who took Challa’s inaugural CRISPR/Cas9 zebrafish lab course two years ago, when it was limited to 10 students. “In chemistry lab, everyone knows what’s going to happen. Here, we don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Using CRISPR/Cas9, the UAB students this year targeted unexplored portions of a gene known to act in eye development. Mutations could possibly give rise to a cyclops embryo.

“These kids are really good, very excited,” said Challa, a research instructor in the UAB School of Medicine’s Department of Genetics. “They come so eager to learn — that’s the trait one needs.”

Working in groups of four, the students targeted different DNA sequences and used custom RNA guides with the CRISPR/Cas9 to try to mutate those targets in fertilized eggs. On the evening of March 8, while viewing fish embryos through a dissecting microscope, Andersen discovered her first cyclops.

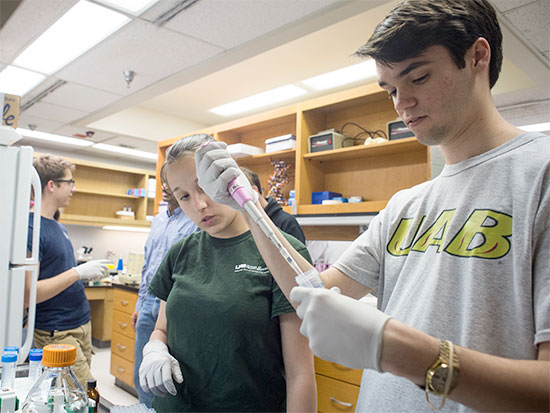

Jordan McGill, watched by John Gotham, transfers an aliquot.“Now comes the exciting part,” Challa told the students as he leaned back against the lab wall. “We clone the gene and see exactly where the mutation is. “We want to learn ‘what is the nature of the mutation?’ and ‘what is the consequence of the mutation on the protein sequence?’”

Jordan McGill, watched by John Gotham, transfers an aliquot.“Now comes the exciting part,” Challa told the students as he leaned back against the lab wall. “We clone the gene and see exactly where the mutation is. “We want to learn ‘what is the nature of the mutation?’ and ‘what is the consequence of the mutation on the protein sequence?’”

At that point, the students had just four more two-hour labs to get their data, and one more week to create posters with their experimental results for the undergraduate research UAB Spring Expo.

Do you have the research bug?

Course-based exposure to hands-on research can serve greater numbers of students than the model of a single student/single research mentor, and students get to discover whether they have the research bug.

“The students self-select whether to go on to a mentorship,” said Diane Tucker, a UAB professor of psychology and director of the Science and Technology Honors Program in the UAB Honors College. “I see it as a win/win.”

Challa agrees. “Some students say, ‘I really enjoyed the class, but I now know it’s not what I want to do.’ A couple of kids may say, ‘I need to find a lab! I need to find a lab!’”

Yazen Shihab, an Alabama native and a UAB neuroscience freshman whose mother came to Montgomery from Jordan, was part of this year’s class.

“I jumped at the chance to join this course because I knew it would be a very valuable, unique experience,” Shihab said after the semester ended. “Unlike any lab course I’ve taken before, molecular genetics was extremely hands-on and promoted class discussion and brainstorming, rather than listening to lectures.”

“Experiencing this unique structure, the course taught me many valuable skills,” Shihab said. “I also, unexpectedly, gained the skill to be more open-minded when learning. Dr. Challa stressed that many people believe they already ‘know’ a topic, which inhibits them from learning anything at all. I took this and became open to learning more, even on topics I thought I knew about. This ultimately allowed me to approach and learn subjects at a different angle.”

Shihab says his love for research has grown, and he now approaches complex subjects in a completely different manner.

‘Solidified my decision to be a doctor’

Ivy Bookout, a freshman neuroscience student who went to high school near Memphis, says Challa’s class really affected what she wants to do in the future.

Mia Rodgers discusses the search for mutant zebrafish embryos with Anil Challa.“It solidified my decision to be a doctor and not go into research,” said Bookout, who was a volunteer grief counselor at the same summer camp where she received grief counseling after her mother died when Bookout was 4. “I learned that I am not a big wet-lab person, and I much prefer interaction with patients.”

Mia Rodgers discusses the search for mutant zebrafish embryos with Anil Challa.“It solidified my decision to be a doctor and not go into research,” said Bookout, who was a volunteer grief counselor at the same summer camp where she received grief counseling after her mother died when Bookout was 4. “I learned that I am not a big wet-lab person, and I much prefer interaction with patients.”

Bookout says she got more out of Challa’s class than a normal lab because he taught actual research techniques.

Cerissa Nowell, a Louisiana native who was raised in Trussville and has wanted to come to UAB since she was 12, says Challa’s class let her explore genetics in a way she was never able to do before.

“In high school and your general chemistry labs in college, they give you some sort of procedure to follow, and you should always get a pretty good result because they are ‘easier’ labs,” said Nowell, who is in the first generation of her family to go to college. “But with Dr. Challa’s lab, you could follow the procedure to a T and get a different result than you expected because the organism ‘fixed itself,’ or the mutation might have been so small that it didn’t make a difference.”

“I learned that I definitely will continue pursuing a career in genetic research,” said the double-major student in neuroscience and genetics and genomic sciences. “I knew before college that I wanted to do research in the genetics field, but this class confirmed my love for it. I really like seeing what can happen when the genome is altered a bit, and learn what makes an organism that specific organism.”

‘I have learned to think’

Baraa Hijaz, a freshman neuroscience student and native Californian who grew up in Alabama, said that Challa’s lab course “was like none other.”

“From his very first lecture, I knew that his class was going to be a new, invaluable experience,” Hijaz said. “Dr. Challa’s approach is very hands-off and encourages the students to unleash their dormant critical thinking and analysis skills that are not traditionally tapped in a conventional classroom setting.”

Hijaz’s parents were emigrants from the war-torn, poverty-stricken country of Palestine; but Hijaz said he was “a relatively normal kid” in Montgomery, where he enjoyed high school varsity soccer and “the wonderful solitude of the gaming world.” He had little interest in academics until he read books like Norman Doidge’s “The Brain that Changes Itself,” which describes how the brain — even into old age — can alter its own structure and function as a neuroplastic, living organ. Hijaz found himself drawn to UAB’s neuroscience program.

Challa, Hijaz said, “has a passion for teaching and asking questions that makes the learning experience all the better. In his course, I have learned to think beyond what I thought to be my limits at the time and have used this skill to solve what had then appeared as daunting tasks.”

John Gotham and Victoria Miller, pipetting.“His wonderful words and advice,” Hijaz said of Challa, “continue to resonate with me and will continue to have an impact on my future.”

John Gotham and Victoria Miller, pipetting.“His wonderful words and advice,” Hijaz said of Challa, “continue to resonate with me and will continue to have an impact on my future.”

‘A unique experience’

Victoria Miller, a freshman biomedical science student who grew up in south Mississippi, said Challa’s class “was a unique experience for me.”

“I did things such as micro-pipetting and injecting embryos that I would have never done in my other lab-based classes,” the Pascagoula High School graduate said. “I got experience doing real science in practical ways that my work actually contributed to a measurable, valuable outcome. This class felt like I was doing real science, unlike my other lab classes where I felt like I was basically doing play-science.”

“Though I am not interested in genetics as a career, I am still incredibly grateful for the hands-on work, and I feel like it helps give me a unique experience that other students do not have,” Miller said. “I wish more students had this type of opportunity.”

Ten of the students in Challa’s course this year are enrolled in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences, four are in the UAB School of Health Professions and two are in Biomedical Engineering, a joint department of the UAB School of Engineering and the UAB School of Medicine.

Support for the course came from the UAB Center for Teaching and Learning, and from the UAB School of Medicine’s Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology and the Transgenic and Genetically Engineered Models (TGEMs) Core facility.

Course-based research experiences (CURE) in the UAB Science and Technology Honors ProgramDiane Tucker, directorWhat

Why

Possible opportunities in other UAB majors?

A benefit for upper classmen in STEM majors?

|