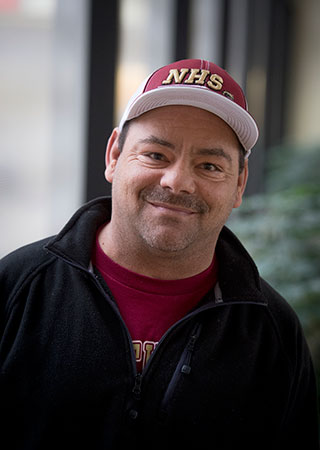

“This will be my first time to be a healthy person. You don’t know what that means. It’s hard to describe what that means. I just know I’m looking forward to it, and I can’t wait,” said Thompson.Tommy Thompson was born in December of 1973 with a horseshoe kidney, a condition in which the kidneys fuse together at the lower end during fetal development. It’s a debilitating disorder that led to more than 40 surgeries of different types for Thompson by the time he was a young adult. Some of the surgeries were aimed at correcting the condition; others were an attempt to make dialysis possible so he could stay alive.

“This will be my first time to be a healthy person. You don’t know what that means. It’s hard to describe what that means. I just know I’m looking forward to it, and I can’t wait,” said Thompson.Tommy Thompson was born in December of 1973 with a horseshoe kidney, a condition in which the kidneys fuse together at the lower end during fetal development. It’s a debilitating disorder that led to more than 40 surgeries of different types for Thompson by the time he was a young adult. Some of the surgeries were aimed at correcting the condition; others were an attempt to make dialysis possible so he could stay alive.

Finally, on Dec. 19 in UAB Hospital at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, at age 41, Thompson had the surgery he has needed most — a living-donor kidney transplant. Thompson received his kidney through UAB’s record-breaking kidney chain. The chain, which began in December 2013, has matched 34 living donors with 34 recipients to create the longest kidney-transplant chain ever recorded in the United States; previously, the longest chain on record involved 30 donors and recipients in 17 hospitals around the country. All 34 recipients in the UAB kidney chain have been transplanted at UAB Hospital or Children’s of Alabama.

In Thompson’s case, the transplant is a prayer that the minister from Cantonment, Florida, says has been answered.

“One of the reasons this transplant is so special to me is that I’ve never been a healthy dad. I’ve never been a healthy husband or preacher,” Thompson said. “This will be my first time to be a healthy person. You don’t know what that means. It’s hard to describe what that means. I just know I’m looking forward to it, and I can’t wait.”

Thompson’s transplant was made possible the same way the previous 33 transplants in the chain were — by the selflessness of a total stranger. Thompson received his kidney from 38-year-old Chicago, Illinois, native Linda Hessenberger, who donated on behalf of her aunt, Cathy Vandiver of Tuscumbia, Alabama. Vandiver received her kidney from Mobile, Alabama, native Felisa Goodwin on Dec. 11.

“My Aunt Cathy is not one to complain, and I didn’t really know how bad she needed a kidney until I was visiting my mom this past summer,” Hessenberger said. “But Cathy told us what was going on, and it really bummed me out. I filled out the information online to be a potential donor, and they contacted me to come in and be tested, and everything went pretty quickly after that. It was just something I felt like I had to do; it was something I wanted to do. The fact that I got to help my aunt and someone else by donating on her behalf … is just awesome. It just makes it that much more special.”

A desire and willingness to help others is the reason this chain has reached a record 34 transplants, says Jayme Locke, M.D., surgical director of the Incompatible Kidney Transplant Program in UAB Hospital and coordinator of the chain.

"It was just something I felt like I had to do; it was something I wanted to do. The fact that I got to help my aunt and someone else by donating on her behalf … is just awesome. It just makes it that much more special,” said Linda Hessenberger, left, with Aunt Cathy Vandiver.“From the very beginning, this chain has represented a real sense of community,” Locke said. “Every person involved has wanted to give back and give to others, which is why we have been able to help people beyond what many chains in the country and around the world have ever been able to do. This sense of community and commitment is truly unique, especially here in Alabama and the Southeast. It’s a very powerful story.”

"It was just something I felt like I had to do; it was something I wanted to do. The fact that I got to help my aunt and someone else by donating on her behalf … is just awesome. It just makes it that much more special,” said Linda Hessenberger, left, with Aunt Cathy Vandiver.“From the very beginning, this chain has represented a real sense of community,” Locke said. “Every person involved has wanted to give back and give to others, which is why we have been able to help people beyond what many chains in the country and around the world have ever been able to do. This sense of community and commitment is truly unique, especially here in Alabama and the Southeast. It’s a very powerful story.”

The chain began Dec. 5, 2013, with Pelham, Alabama, resident and donor Paula Kok, who approached UAB about the possibility of donating a kidney to someone in need and was committed to donating a kidney despite not having an intended recipient.

In a paired transplant chain, a donation like Kok’s can set off a series of transplants in which family or friends of recipients give a kidney to another person in need — essentially paying donations forward on behalf of a loved one.

Kok’s altruistic gift launched a chain of transplants that changed the lives of people in nine states — Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana, Texas, Illinois and New Jersey — and even endured a January snowstorm that crippled the Southeast the week of Jan. 27.

Kok’s decision to donate to someone — anyone — in need still resonates with donors and recipients a full year later.

“It’s a very selfless thing for someone to come forward and be willing to donate to start something like this,” said John Woolard, the 33rd donor in the chain. “That is a huge commitment, which undoubtedly makes an impact on others. Following after someone is easier oftentimes than taking the first step. It’s a testament to God’s grace and His example of how He can use one person to reach many.”

Selwyn Vickers, M.D., senior vice president for Medicine and dean of UAB’s School of Medicine, says the kidney chain highlights UAB’s commitment to academic excellence and clinical innovation for lifesaving treatments that reach beyond standard clinical techniques. “The goal of our programs,” he said, “is to have a resounding impact on health care across the country. This kidney-transplant chain demonstrates our pledge.”

| “This chain really showcases the power of the human spirit in every aspect. Every one of these individuals involved possesses special gifts — determination, love for their fellow man, a thirst for knowledge and passion. These are precious gifts that encapsulate the very essence of life. Our entire staff is honored to serve these families and be a part of each of their journeys.” |

Vickers also pointed to the hard work and dedication of numerous surgeons, nephrologists, nurses, kidney-transplant coordinators and support staff as an instrumental part of the success of the incompatible kidney-transplant program. Vickers says this devotion, along with the perseverance of the transplant recipients, donors and their families, made this chain possible.

“What has been accomplished with this chain speaks to the commitment of numerous people — especially the transplant recipients, donors, and our entire UAB transplant surgical, clinical and research teams,” Vickers said. “This chain really showcases the power of the human spirit in every aspect. Every one of these individuals involved possesses special gifts — determination, love for their fellow man, a thirst for knowledge and passion. These are precious gifts that encapsulate the very essence of life. Our entire staff is honored to serve these families and be a part of each of their journeys.”

Sixty-seven of the 68 surgeries in the chain to date have been performed at UAB Hospital. One recipient, 15-year-old Ryane Burns of Union, Mississippi, was transplanted at Children’s of Alabama, making it the only program in the Southeast to offer living-kidney paired donation to recipients younger than 18.

UAB’s program — the South’s leading incompatible kidney-transplant program — makes transplantation possible between some donors and recipients who otherwise would not match. It also fills a major need in Alabama, where more than 3,700 men, women and children are on the nation’s second-largest waiting list for a kidney transplant.

Living-donor kidney transplantation is not rare, but many programs require a completely compatible match. Consequently, many of the transplants UAB surgeons perform, including several in this chain, would not have occurred through a national paired-exchange program. UAB’s program offers patients pretreatment to overcome blood group and/or HLA barriers to compatibility. Paired donations also improve compatibility and make the transplants less challenging. UAB’s program of combining desensitization with paired donation is unique in the Southeast.

“UAB has become a national leader in kidney transplantation since performing our program’s first kidney transplant in 1968,” said Devin Eckhoff, M.D., director of UAB’s Division of Transplantation. “Our kidney program has done more living-donor transplants than any other program in the United States since 1987, and it is one of the three largest kidney-transplant centers in the nation. Our experience in performing kidney transplants from living donors ensures the highest level of care and better outcomes for our patients — both kidney donors and recipients.”

The chain doesn’t end with Thompson; more transplants are planned in January 2015. Denise Prewitt is a bridge donor who is expected to be part of the chain in the New Year. She is donating on behalf of Marjorie Wilhite who received her kidney this past summer.

“I’m excited and ready to help when it’s my turn,” Prewitt said. “This chain is just amazing to me, totally wonderful. I’ve always been a blood and plasma donor. Anything I can do to help is just an honor.”

Thompson, for one, says he will always be grateful to those who chose to give before and after him.

“I think this chain goes to show that we never know the power of the one life we have, how many people you can touch,” Thompson said. “It’s amazing to know that all of these transplants come from one person who was willing to give of herself. That’s just a powerful thought. To know that in your one life, you can touch so many.”

Read more about the UAB kidney chain, including stories from many of those involved, at www.uab.edu/kidneychain, and join the conversation online at www.facebook.com/uabkidneychain and on Twitter at #uabkidneychain.

To become a living-kidney donor, visit uabmedicine.org/kidneytransplant, or to indicate your interest in donating your organs after death, visit www.organdonor.gov and sign up today.