Written by Christina Crowe

Written by Christina CroweThe second annual Community Engagement Institute enjoyed an overflow crowd for the daylong education and training event designed to benefit both community and academic partners.

The event, held Oct. 2 at the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex, was organized by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for Clinical and Translational Science’s One Great Community Council and the UAB Center for the Study of Community Health’s Jefferson County Community Participation Board.

Author and physician Sampson Davis, M.D., addressed the more than 250 individuals in attendance about the importance of family and community support in cultivating personal success. Davis returned to his hometown of Newark, New Jersey, after graduating from medical school where he and two of his high school friends — who also became doctors — started an organization called The Three Doctors. Their goal is to spread the word of health, education and youth mentoring, and become “the Michael Jordan of education,” so that learning becomes a glamorized trend throughout all communities.

In the afternoon, Al Richmond, MSW, executive director, Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, shared some of what he has learned in his more than 25 years in a career that uniquely blends social work and public health to address racial and ethnic health disparities.

“This event is setting the stage for enhanced community engagement, for learning about what people can do in their own communities, as well as displaying the variety of resources available at UAB,” Richmond said.

This year’s CEI event was free to the public, and attendance more than doubled from last year. Attendees represented members of more than 100 Greater Birmingham faith-based organizations, universities, government and nonprofit agencies, local and state health department representatives, community organizers, city and county officials, and representatives from the National Institutes of Health and the Environmental Protection Agency.

| The CEI’s breakout sessions touched on three topics: activism, advocacy and community organizing; structural racism and community health; and ways to fully involve communities in collaborative research. |

New this year, the CEI poster session featured more than 30 posters on an array of public health topics, including domestic violence and HIV awareness and prevention programs, and other projects dedicated to tackling tough local public health issues. Event attendees were encouraged to network and receive a directory of all attendees’ names to facilitate future collaborations.

Max Michael, M.D., dean of the UAB School of Public Health, emphasized the importance of working to foster collaborations between higher education institutions and their larger communities.

“The momentum for this event continues to grow,” Michael said, “and reflects the desire by our Greater Birmingham community members from a broad range of organizations to have a platform to engage in meaningful conversations about how we can improve our communities’ public health.”

“We continue to be encouraged by the response to this important event, which highlights the deep knowledge, experience and talent in our communities,” said Shauntice Allen, Ph.D., director of One Great Community. “We plan to harness the momentum the CEI generates to work toward achieving, and maintaining, improved health outcomes for our community as a whole.”

Videos of Davis’ and Richmond’s talks, as well as photos of the event, are available on the CEI website, www.uab.edu/ccts/cei.

HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology

is hoping to stimulate public interest, especially among students, in the growing field of computational and informatics-based education. The Institute will be featured in the upcoming PBS national television program American Graduate Day.

is hoping to stimulate public interest, especially among students, in the growing field of computational and informatics-based education. The Institute will be featured in the upcoming PBS national television program American Graduate Day. Neil Lamb, PhD, Vice President for Educational Outreach and Liz Worthey, PhD, at HudsonAlpha will represent HudsonAlpha in the upcoming national television program which will air live from WNET in New York on Saturday, October 3 from 11 am – 6 pm, CDT.

“Genetics and genomics are burgeoning fields of study, and we need to inspire and grow a workforce in those fields. In addition, all students will need basic genomics knowledge to make informed decisions about the tests we take, the foods we eat, and how we pursue better health,” Dr. Lamb said. Dr. Lamb and Dr. Worthey will focus their conversation on HudsonAlpha’s education programs which are aimed at growing a new generation of genomic savvy youth.

Merrimack Hall, a Huntsville-based center that provides visual and performing arts education and cultural activities to children and adults with special needs, also will be featured in American Graduate Day.

Sponsored by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the American Graduate Day program is public media’s long-term commitment to supporting community-based solutions to the dropout crisis. For more information regarding this or other initiatives at HudsonAlpha, please contact: Maureen Mack, 256-5216 /

These days, you can have your genome sequenced for a few thousand dollars, and store it (just barely) on a 100-gigabyte hard drive. There are all kinds of potentially useful data points in that sea of nucleotides. Researchers have identified mutations that increase your risk of colon cancer, and affect your ability to process pain medications, to name two out of thousands and thousands of clinically useful discoveries. But how does that knowledge translate into action at your doctor’s office? Do you need accelerated colon cancer screenings? How can you get a permanent warning in your medical record that you won’t respond well to opioid drugs?

Call that the “information in” problem, and it’s not limited to genetic data. Every few years, the medical literature doubles in size. In 2014, there were 3 million new studies published in cancer alone.

“We’ve collected all these data and invested all these resources to ultimately help patients,” said James Cimino, M.D., director of the Informatics Institute in the UAB School of Medicine and co-director of the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science. “If doctors and nurses aren’t able to put that information to use, we have wasted a huge amount of money.” (READ MORE...)

August 21, 2015

By Jim Bakken

The National Institutes of Health has awarded the University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for Clinical and Translational Science $33.59 million over four years to continue the center’s programs advancing translational research. Since its initial funding in 2008 through Alabama’s only Center for Translational Science Award to work toward innovative discoveries for better health, the UAB CCTS has nurtured UAB research, accelerating the process of translating laboratory discoveries into treatments for patients, training a new generation of clinical and translational researchers, and engaging communities in clinical research efforts.

The CCTS will continue to advance its mission to accelerate the delivery of new drugs, methodologies and practices to patients at UAB and throughout a partner network of 11 institutions in the Southeast. (READ MORE...)

CCTS specializes in turning ideas into action

By Matt Windsor

UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, which just received a $34 million grant renewal, has supported hundreds of investigators at UAB and beyond.

In 2006, Congress launched the Center for Translational Science Award (CTSA) program to help accelerate the rate at which research discoveries are transformed into practical applications.

The barriers are numerous: Sometimes it’s a lack of funds to pursue a promising hunch, or access to adequately trained staff to make a clinical trial possible — or simply the absence of an experienced mentor to show an investigator how to take the next step. (READ MORE...)

August 10, 2015

August 10, 2015 By Matt Windsor

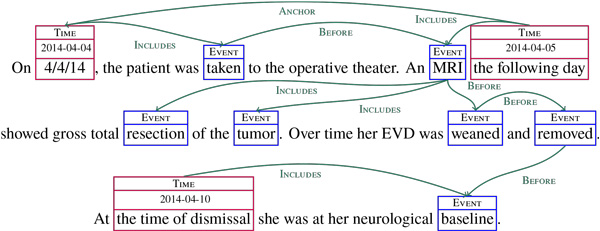

By training computers to pick out timing clues in medical records, UAB machine learning expert Steven Bethard, Ph.D., aims to help individual physicians visualize patient histories, and researchers recruit for clinical trials.

Train a computer to read medical records, and you could do a world of good. Doctors could use it to look for dangerous trends in their patients’ health. Researchers could speed drugs to market by quickly finding appropriate patients for clinical trials. They could also find previously overlooked associations. By keeping track of data points across tens of thousands, or millions, of medical records, computer models could find patterns that would never occur to individual researchers. Maybe Asian women in their 40s with type 2 diabetes respond well to a certain combination of medications, while white men in their 60s do not, for example.

Machine learning, in particular a branch called natural language processing, has had plenty of successes recently. It’s the secret sauce behind IBM’s “Jeopardy”-winning Watson computer and Apple’s Siri personal assistant, for instance. But computers still have a tough time following medical narratives.

“We take it for granted how easy it is for us to understand language,” said Steven Bethard, Ph.D., a machine learning expert and linguist in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences Department of Computer and Information Sciences. “When I’m having a conversation, I can use all kinds of crazy constructions and pauses between words, and you would still understand me. All these things make language very difficult for computers, however. They like rules and an order that is followed every time, but languages aren’t like that.”

Timing is everything

So Bethard, the director of UAB’s Computational Representation and Analysis of Language Lab, builds models that help computers catch our drift. In one ongoing project, he is working with colleagues at the Mayo Clinic and Boston Children’s Hospital “to extract timelines from clinical work,” Bethard said. Using text from clinical notes taken at the Mayo Clinic, “we’re working to find all the clinical events mentioned in those notes — things like ‘asthma’ and ‘CT scan,’ for example — and link them to the proper time,” he said. If the computer sees “the patient has a history of asthma,” it should know that’s in the past. If it sees “planning a CT scan,” that’s in the future. “Sometimes you have explicit dates, such as ‘on Sept. 15, the patient had a colonoscopy,’” Bethard said. “But the computer still has to figure out whether that means Sept. 15, 2014, or Sept. 15, 2015.’”

The diagram above illustrates how a computer could extract timeline information out of an entry in a medical record.

A system like this would help individual doctors keep track of their patients’ progress. “If you have had a patient for 15 years, you see so many things,” Bethard said. “Looking at a visual of all the conditions and procedures over that time is extremely useful.” The system could also identify patients for clinical trials. “Say you wanted to find someone who had liver toxicity after they started taking methotrexate,” Bethard said. “The sequence of events is important; you only want to find people who have taken the drug and had liver toxicity in the appropriate order.” Another use: finding new associations between drugs or procedures and adverse events. “If you have a large number of patients, you can say, ‘How often do you see a certain side effect?’ for example,” Bethard said. “You can generate new hypotheses about causality.”

Learning to spot cancer

One of Bethard’s graduate students, John David Osborne, has built a machine-learning model that is already having an impact on the practice of health care at UAB. By day, Osborne is a research associate in the biomedical informatics group of UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science. He and his colleagues were called in to help UAB’s Cancer Registry with a Big Data challenge: tracking and cataloguing cancer diagnoses and treatment outcomes.

Every hospital is responsible for reporting new cases of many different types of diseases to the federal government. “Cancer is one of those diseases, but not all cancers are reportable,” Osborne said. “Lots of skin cancers aren’t, but melanoma is; anything malignant or in the central nervous system is reportable.” Identifying and tracking these cases in pathology reports — and determining whether they are or are not reportable — can be quite challenging at a health care system as large as UAB, Osborne notes. A year and a half ago, the biomedical informatics team at the CCTS created the Cancer Registry Control Panel, which uses natural language processing to detect possible cancer cases in the pathology reports. As an additional research project, Osborne recently designed a machine-learning algorithm that provides additional assistance to the human registrars. “It scans through the records and says, ‘This is a likely case, and here’s why I think that,’” Osborne said. “Humans are still going through every record, but you can speed it up and show them where to look.”

Language matters

Bethard and Osborne build their models using the Unstructured Information Management Architecture — an open-source version of the code IBM used to create Watson.

The first step in building a machine-learning model is to decide what kind of training material to use. “The machine-learning models we create for health information extraction look at gold-standard models that humans have created,” Bethard said. “They say, ‘I see all these patterns in the human timelines, so this is what I’ll look for.’”

Some of these decisions are relatively simple. “Cancer is always a condition of interest,” Bethard said. “Anything related to cancer is something you want to include. The harder pattern to learn is how to link together time and events. A date and then a colon tells you they are describing something that happened on that date. Verb phrases, noun phrases and linguistic structure in time can be very predictive.”

As that description makes clear, natural language processing requires a deep knowledge of English grammar as well as computer code. “The most successful people in this field are hybrids,” adept at linguistics and computer science, Bethard said. He has a bachelor’s degree in linguistics. He shares his interest in language with his wife, who is now completing a postdoctoral fellowship in the cognitive neuroscience of language at the University of South Carolina.

Bethard came to Birmingham in 2013, attracted by ongoing research in natural language processing in UAB’s computer science department. “For me, it makes a lot of sense to be at a place with a major medical school,” Bethard said. He is looking forward to collaborations with James Cimino, M.D., Ph.D., the inaugural director of the School of Medicine’s new Informatics Institute and a renowned expert in the creation and manipulation of electronic medical records. “He’s famous, very well-known and well-respected,” Bethard said of Cimino. “He knows about all the range of problems: getting information from the text that doctors write, how to input this data, how to store it — the whole spectrum.”

Teaching computers to navigate the ambiguity of the English language can be trying, but the opportunities at UAB are exciting, Bethard says. “There is plenty of data available here, and clear challenges for these models to address.”

- UAB Professor of Business Works to Revitalize Bush Hills Neighborhood Using a Community Health Innovation Award Grant

- Community Health Innovation Awards Pivotal to Naming of UAB to 2014 President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll

- CCTS KL2 Mentored Career Development Awards - Invitation for LOI

- CTSA Think Tank Series: “Connecting the CTSA Program to the NIH SBIR/STTR Program"