In rural Wilcox County, the Affordable Care Act has expanded the number of residents who can benefit from care. But the number of physicians has stayed the same: just three, who must serve more than 12,000 people.

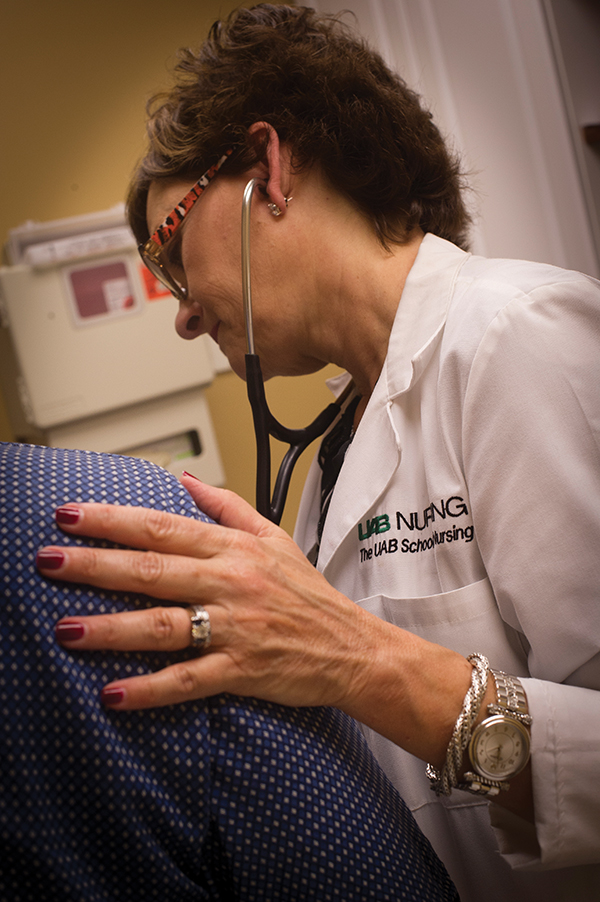

The imbalance keeps Sheena Champion, M.S.N. (pictured above), quite busy. Adult nurse practitioners like Champion, who graduated from the UAB School of Nursing in 2011, are key to making health care available and accessible to residents in many Alabama communities with a shortage of doctors. She works alongside Willie White, M.D., providing primary care in a medical clinic in Camden, and her responsibilities have “grown immensely” over the last three years, she says.

Champion’s role is one that will continue to rise in importance as the number of medical students choosing to specialize in primary care remains small, and as America’s aging population demands more care of every kind. With nurse practitioners (NPs) uniquely positioned to help fill the void, the UAB School of Nursing is growing its training programs to help meet the needs of patients statewide.

The imbalance keeps Sheena Champion, M.S.N. (pictured above), quite busy. Adult nurse practitioners like Champion, who graduated from the UAB School of Nursing in 2011, are key to making health care available and accessible to residents in many Alabama communities with a shortage of doctors. She works alongside Willie White, M.D., providing primary care in a medical clinic in Camden, and her responsibilities have “grown immensely” over the last three years, she says.

Champion’s role is one that will continue to rise in importance as the number of medical students choosing to specialize in primary care remains small, and as America’s aging population demands more care of every kind. With nurse practitioners (NPs) uniquely positioned to help fill the void, the UAB School of Nursing is growing its training programs to help meet the needs of patients statewide.

Nurse practitioner Sheena Champion is part of a team bringing much-needed primary care to an underserved Alabama community.

Nurse practitioner Sheena Champion is part of a team bringing much-needed primary care to an underserved Alabama community.

Evolving Roles

Since their introduction in the 1960s, NPs have partnered with physicians, registered nurses, physical therapists, and other health professionals in a team approach to care. “NPs are an integral part of these teams because most nurses have provided direct patient care, which has made us approachable and trustworthy sources,” Champion says.

Today, NPs lead some of those teams and work in all types of health-care settings, says Linda Moneyham, Ph.D., the School of Nursing’s senior associate dean for academic affairs. “Originally, the NP was conceptualized as a primary-care role,” she explains. “Over time, it quickly evolved for acute settings and just about anywhere a nurse could be found.”

NP duties have expanded, in some part, because nurses themselves wanted to take on more advanced practice roles, Moneyham says. But physicians also have recognized the value that NPs bring to their work. For instance, some orthopedic surgeons hire NPs to go on rounds with them, participate in surgery, and see patients from the emergency department, Moneyham says. “NPs help them manage the load.”

And with the Affordable Care Act pushing to increase access, the health-care community has realized that “NPs are one way to do that,” Moneyham says. “We can produce many more NPs in a year than we can primary-care physicians.”

In June 2013, Governor Robert Bentley signed a law—jointly supported by the Alabama Medical Association, the Board of Medical Examiners, and the Nurse Practitioner Alliance of Alabama—granting prescribing authority to Alabama-based NPs. Such changes “have given me opportunities to perform every skill within my scope of practice,” says Aimee Chism Holland, D.N.P., coordinator of the School of Nursing’s dual NP specialty track in adult-gerontology primary care and women’s health. And because the waiting list to see some doctors is three to six months long, the new authority means that NPs can respond to patient needs in a way that helps to shorten the backlog, she adds.

Today, NPs lead some of those teams and work in all types of health-care settings, says Linda Moneyham, Ph.D., the School of Nursing’s senior associate dean for academic affairs. “Originally, the NP was conceptualized as a primary-care role,” she explains. “Over time, it quickly evolved for acute settings and just about anywhere a nurse could be found.”

NP duties have expanded, in some part, because nurses themselves wanted to take on more advanced practice roles, Moneyham says. But physicians also have recognized the value that NPs bring to their work. For instance, some orthopedic surgeons hire NPs to go on rounds with them, participate in surgery, and see patients from the emergency department, Moneyham says. “NPs help them manage the load.”

And with the Affordable Care Act pushing to increase access, the health-care community has realized that “NPs are one way to do that,” Moneyham says. “We can produce many more NPs in a year than we can primary-care physicians.”

In June 2013, Governor Robert Bentley signed a law—jointly supported by the Alabama Medical Association, the Board of Medical Examiners, and the Nurse Practitioner Alliance of Alabama—granting prescribing authority to Alabama-based NPs. Such changes “have given me opportunities to perform every skill within my scope of practice,” says Aimee Chism Holland, D.N.P., coordinator of the School of Nursing’s dual NP specialty track in adult-gerontology primary care and women’s health. And because the waiting list to see some doctors is three to six months long, the new authority means that NPs can respond to patient needs in a way that helps to shorten the backlog, she adds.

D'Ann Somerall helps to train UAB nursing students for primary- and specialty-care roles in a variety of clinical settings.

D'Ann Somerall helps to train UAB nursing students for primary- and specialty-care roles in a variety of clinical settings.Specialty Training for Underserved Areas

As NP roles change across the state, the School of Nursing’s master’s program for NPs has more than tripled in enrollment over the past nine years, Moneyham says. Though primary care remains the area with the greatest needs, the program also offers 10 specialty tracks and optional subspecialties for NP students. The format enables many students working toward becoming adult NPs to add a subspecialty, such as oncology or women’s health, to serve more specific patient needs.

“Toward the end of the seven-semester program, the students have the option of performing a portion of their clinical hours in a specialty area,” says D’Ann Somerall, D.N.P., UAB’s family nurse practitioner specialty track coordinator. “Many students select specialties that are limited in the area of the state where they wish to practice in order to expand their knowledge base, and also to build relationships with providers.”

Recently, UAB launched new NP tracks in palliative care and diabetes management. Feedback from alumni working in communities throughout the state has inspired the addition of each specialty. Several years ago, for instance, school leaders realized that many graduates of the NP track in women’s health returned to complete a primary-care track to better serve their patients. As a result, the school created the dual adult-gerontology primary care and women’s health specialty track. Just a year later, the program began to see exponential growth, leaping from about 10 students annually to an average of 40 each year.

“We train NPs to see patients and perform all the procedures in a primary care or women’s health clinic,” Holland says of the dual program. “Employers love our graduates. With them, primary-care clinics can meet women’s health needs without referring patients elsewhere or making them wait months. It’s been a huge success, all because we looked at the needs of the public and trained our students to meet those needs.”

UAB also added a doctor of nursing practice (D.N.P.) program in 2010. “The D.N.P. degree will continue to change the role of NPs,” Holland says. “We’ll see more NPs leading health-care teams, owning clinics, sitting on professional boards to guide policy, and doing research to identify and meet care needs.”

“Toward the end of the seven-semester program, the students have the option of performing a portion of their clinical hours in a specialty area,” says D’Ann Somerall, D.N.P., UAB’s family nurse practitioner specialty track coordinator. “Many students select specialties that are limited in the area of the state where they wish to practice in order to expand their knowledge base, and also to build relationships with providers.”

Recently, UAB launched new NP tracks in palliative care and diabetes management. Feedback from alumni working in communities throughout the state has inspired the addition of each specialty. Several years ago, for instance, school leaders realized that many graduates of the NP track in women’s health returned to complete a primary-care track to better serve their patients. As a result, the school created the dual adult-gerontology primary care and women’s health specialty track. Just a year later, the program began to see exponential growth, leaping from about 10 students annually to an average of 40 each year.

“We train NPs to see patients and perform all the procedures in a primary care or women’s health clinic,” Holland says of the dual program. “Employers love our graduates. With them, primary-care clinics can meet women’s health needs without referring patients elsewhere or making them wait months. It’s been a huge success, all because we looked at the needs of the public and trained our students to meet those needs.”

UAB also added a doctor of nursing practice (D.N.P.) program in 2010. “The D.N.P. degree will continue to change the role of NPs,” Holland says. “We’ll see more NPs leading health-care teams, owning clinics, sitting on professional boards to guide policy, and doing research to identify and meet care needs.”

Somerall with a nurse practitioner at the School of Nursing's Foundry clinic.

Somerall with a nurse practitioner at the School of Nursing's Foundry clinic.Increasing Opportunities

Moneyham and Somerall predict that additional legislative changes in the coming years will give NPs more latitude to utilize their skills and help bring greater access to health care to residents across the state. One option is to raise the limits on the number of NPs who can collaborate with each physician.

Current students are ready to take on the extra responsibilities. Amy Jones, B.S.N., R.N., a student in the dual adult-gerontology and women’s health NP program, expects to “practice in various settings and offer needed primary and preventive health-care services, including diagnosing and treating numerous illnesses and minor injuries, prescribing medications, educating patients regarding their health, and coaching them to meet their health goals.

“I think we will see an increase in clinical and administrative employment opportunities for NPs,” Jones says. “And I predict that NPs will demonstrate improved patient outcomes that may warrant the acquisition of enhanced clinical privileges from state governments.”

Right now, “there are more needs than we could ever adequately provide care for,” Moneyham says. “Physicians who collaborate with NPs know that bigger teams mean more patients, better care, and better outcomes.”

• Discover UAB's master's program to train nurse practitioners.

• Give something and change everything for students at the UAB School of Nursing.

Current students are ready to take on the extra responsibilities. Amy Jones, B.S.N., R.N., a student in the dual adult-gerontology and women’s health NP program, expects to “practice in various settings and offer needed primary and preventive health-care services, including diagnosing and treating numerous illnesses and minor injuries, prescribing medications, educating patients regarding their health, and coaching them to meet their health goals.

“I think we will see an increase in clinical and administrative employment opportunities for NPs,” Jones says. “And I predict that NPs will demonstrate improved patient outcomes that may warrant the acquisition of enhanced clinical privileges from state governments.”

Right now, “there are more needs than we could ever adequately provide care for,” Moneyham says. “Physicians who collaborate with NPs know that bigger teams mean more patients, better care, and better outcomes.”

• Discover UAB's master's program to train nurse practitioners.

• Give something and change everything for students at the UAB School of Nursing.