You know the drill: Your dentist diagnoses you with a cavity. Then there’s a shot and a filling, and you’re on your way. Problem solved.

But cavities aren’t as simple as they might seem. For example, why are they are more prevalent among minorities and people with lower socioeconomic status? Why do they appear to be linked with health problems in other areas, such as the heart? A team of UAB researchers has been trying to answer these and other questions, and their discoveries could lead to new solutions to help prevent cavities in the first place.

Multiple Causes of Caries

In 2000, Stephanie Momeni received a job offer to work in UAB’s Specialized Caries Research Center, part of the UAB School of Dentistry, as a laboratory technician. “Caries” is the scientific term for cavities and tooth decay, which is the breakdown of teeth due to bacterial activity. Momeni was tasked with investigating the epidemiology, or prevalence, of dental caries—work that would eventually lead her to complete a Ph.D. in biology from UAB.

In the lab, she worked alongside Noel Childers, D.D.S., the Joseph F. Volker Endowed Chair and chair of the Department of Pediatric Dentistry, who focuses on the prevention of dental caries. That can be a challenge, considering that diet, behavior, microbiology, genetics, and the immune system all can play a role in the formation and growth of caries. “That’s what makes it so difficult for us to say ‘here’s what causes it, so we can cure it,’” Childers says.

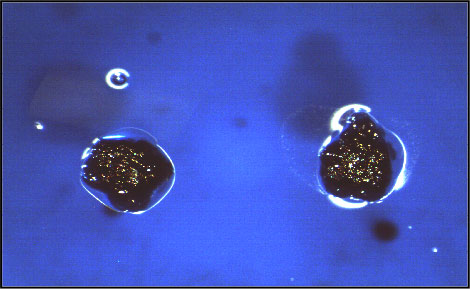

Streptococcus mutans is the bacteria most commonly associated with dental caries.

Streptococcus mutans is the bacteria most commonly associated with dental caries.Mouth to Mouth

Though dental caries are a major problem nationwide, children in the Black Belt counties of Alabama are especially at risk. (According to a UAB study, 70 percent of eight-year-old African-American children in one community showed evidence of tooth decay.) Lack of access to care is one reason, says Momeni. Perry County, for example, does not have a pediatric dentist, meaning that residents must travel more than 30 miles to Selma to receive care. For people without access to a car, or for those living in poverty, the challenge is even greater. “The general mentality is that you don’t go to the dentist until there’s pain or another problem, and by that point, it’s too late to do anything about it,” Momeni says.

Childers and his team wanted to know if the presence of certain types of bacteria also impacted the prevalence of dental caries in Black Belt children. Over eight years, the scientists partnered with a community in Perry County for a first-of-its-kind research project, gathering 14,000 samples from 400 children and adults. They also provided study participants with preventive care, including toothbrushes and fluoride treatments. “Unfortunately, even with our preventive care, we still saw a lot of caries,” Childers says.

Childers, Momeni, and their colleagues specifically wanted to track the spread of Streptococcus mutans, the specific bacteria most commonly associated with dental caries, among African-American children. Traditionally, studies such as this one would investigate whether a child shares any specific bacterial strains, or genotypes, with his or her mother. But Momeni also evaluated the number of genotypes that children did not share with their mothers. It turns out that approximately half of the 119 children in the study shared at least one genotype with their mothers—along the lines of what similar studies have found. Then she made a surprise finding: 72 percent of the children had at least one genotype not shared with any member of their families, providing strong evidence of child-to-child transmission of S. mutans.

The large number of samples and eight-year timeframe is “a different scale than what other researchers have done in the past, so it gives us a little more detail on how and when people are getting the bacterial strains, and which ones may be associated with disease,” Momeni says. “One key advantage of a study like ours is the factor of time. When we accounted for time, we started to see patterns in the data.”

By shedding light on S.mutans transmission methods, the research could help cavity prevention and treatment.

By shedding light on S.mutans transmission methods, the research could help cavity prevention and treatment.Any interaction involving saliva, like sharing an ice cream cone, cup, or straw, could help the microbes jump from mouth to mouth, Momeni says. “The study illuminates the need to consider these transmission routes in dental caries risk assessments, prevention, and treatment strategies,” she notes.

Next, Momeni wants to investigate whether the presence of multiple bacterial strains increases caries risk—and if particular combinations of bacteria are more problematic than others.

An Effect on Heart Health?

Momeni’s research also could help shed light on potential connections between organisms linked with an increase of inflammation in the body that may be associated with cardiovascular disease.

While most of the S. mutans bacteria linked with dental caries are of a variation known as serotype c, Momeni and her colleagues found serotype k among children in the Perry County study. This result was another surprise: Serotype k is not considered to be part of the normal community of oral bacteria, but it has been associated with bacterial endocarditis and other inflammatory cardiovascular problems.

“Our lab was the first in the country to report serotype k in the U.S.,” Momeni says. This strain was originally found by Japanese investigators whose research suggests that it can enter the bloodstream and travel to the heart, potentially contributing to the development of heart disease. Momeni would like to collaborate with other labs on research to learn more about serotype k and its effects on the body.

A Path to Prevention?

Childers hopes that the team’s discoveries will lead to the development of a preventive approach that can control the spread of S.mutans bacteria. Already, the researchers are beginning to identify avenues for further exploration. For example, the study has shown that children colonized with S. mutans earlier have more severe cavities. “Children who don’t have caries in their primary dentition, in their primary teeth, rarely develop caries in their permanent teeth,” Childers explains. Perhaps one day, an early intervention might help all children reduce their risk—and perhaps prevent additional health problems down the road.

“It’s a big puzzle, but we’ve accumulated a lot of good tools and data,” Childers says. “Now it’s a matter of trying to put the pieces together.”