To an Alabamian, the hum of an air conditioner is sweet, sweet music—from the whir and sputter of a window unit to the muted purr of a sleek new model. But that cool refuge can be costly. With electric bills rising past $200 during the hottest, most humid months, interest in alternative energy sources is spiking.

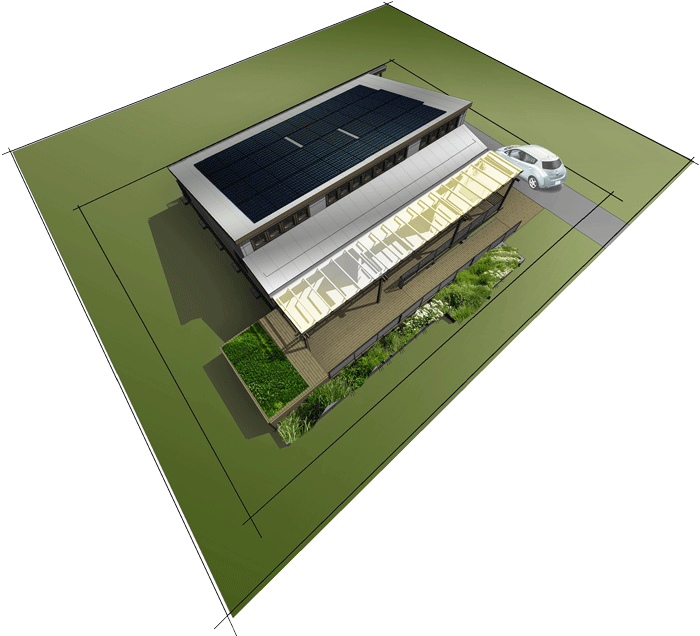

(Above and at bottom) A team of students from all parts of UAB's campus helped design, build, and promote the house.

(Above and at bottom) A team of students from all parts of UAB's campus helped design, build, and promote the house.A team of UAB students is showing the state what solar-powered comfort looks like. Partnering with Calhoun Community College, they have designed and built a house from the ground up for the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon 2017 competition, hosted in Denver, Colorado, in October. There, they will compete against 11 other collegiate teams from around the world for prizes ranging from $100,000 to $300,000.

The 1,000-square-foot house is equipped to run all the usual residential appliances and amenities at the same level as a comparable modern house on a conventional power grid. But the only source of energy comes from what the house can harness from the sun.

“The South is in a good position to incorporate more renewable energy, especially solar, because our latitude is ideal for it,” says Hessam Taherian, Ph.D., project advisor and assistant professor in the UAB School of Engineering. “More renewable and efficient energy could bring down the need for oil, gas, and coal, and be much better for the environment by lowering our society’s carbon footprint.”

A major goal of the Solar Decathlon is to show Americans that solar-powered homes aren’t something “offbeat or weird or kooky,” says Bambi Ingram, program coordinator for UAB Sustainability, and that the homes follow modern construction standards and function like any other residence.

In fact, judges will evaluate whether the Decathlon houses can provide sufficient power for a hot shower and a fully washed, fully dried load of laundry. Students must prepare and host two dinner parties—plus a movie night—in the house for competing teams. The house also must generate enough juice to charge an electric car for a 25-mile drive during the competition.

A rendering depicts the modern living, kitchen, and dining areas inside UAB's Solar Decathlon house. Another illustration (at top) shows off the house's curb appeal.

A rendering depicts the modern living, kitchen, and dining areas inside UAB's Solar Decathlon house. Another illustration (at top) shows off the house's curb appeal.

Model Home

The two-year challenge has required plenty of brainpower. School of Engineering students focused on planning and construction, while Collat School of Business students worked on marketing strategies, and Calhoun Community College students contributed their expertise with solar technology. But the project has attracted students from across campus, such as Nina Morgan, a senior anthropology/sociology major from Sipsey, Alabama.

“The house has a long-term educational component,” says Morgan, a UAB Sustainability intern who helped with communication and marketing. “It exposes the community to different ways to live and to harness energy from natural resources.”

Williams Blackstock Architects worked with students to design the home, and Stewart Perry Construction did the framing. Students completed most of the construction, assisted by local corporate and nonprofit mentors and UAB Facilities. Once the house was built and tested in Birmingham, it had to be taken apart, shipped to Colorado, and reassembled in Denver.

Weathering the Climate

UAB's Solar Decathlon house references its Southern roots while emphasizing energy efficiency and safety. Judges will evaluate each house on its architecture, engineering, and energy performance. Take a closer look at some of the house's features below.

UAB's Solar Decathlon house references its Southern roots while emphasizing energy efficiency and safety. Judges will evaluate each house on its architecture, engineering, and energy performance. Take a closer look at some of the house's features below.The Solar Decathlon requires each home to be suited for its local climate—in Alabama, that means steaming summers and tornado threats. Ingram and Scott Jones, a junior in mechanical engineering from Madison, Alabama, say UAB’s house is up to snuff in both regards.

For example, the house’s desiccant system targets humidity, a key reason Alabamians blast their air conditioning. “The water in the air makes you feel hot,” explains Ingram. “Our desiccant system does some of the work [to remove that water], so we don’t have to air condition as much.”

Jones was instrumental in designing the home’s tornado-proof safe room—a must for a newly built home in a state battered by 65 tornadoes in 2016. The space is lined with stronger-than-steel composite material developed by the School of Engineering.

Such amenities prove that “affordable energy-efficient housing is practical and feasible in [the Birmingham] area,” says Jones, who previously worked for Vulcan Solar Power and helped install one of the city’s largest solar-energy systems atop UAB’s Campus Recreation Center. “That is one of the pillars of the Solar Decathlon.”

Taherian adds that Alabama’s high rate of natural disasters may lead to more reliance on renewable energies like solar. “People will think about having more autonomy and not relying on grids,” he says.

Large front and back porches provide shade and cross ventilation, reminiscent of homes built before air conditioning.

The home faces north and south, protecting the interior from the harsh heat of morning and afternoon sun. Transparent canopies on the northern porch pull natural light inside in early morning and late evening.

Inside the house, ingenious inventions reduce HVAC demand. A solar-powered desiccant system dehumidifies the air. Residents also can summon a robotic cooler — imagine an A/C on wheels — to lower temperatures in portions of the house.

-

Large front and back porches provide shade and cross ventilation, reminiscent of homes built before air conditioning.

-

The home faces north and south, protecting the interior from the harsh heat of morning and afternoon sun. Transparent canopies on the northern porch pull natural light inside in early morning and late evening.

-

Inside the house, ingenious inventions reduce HVAC demand. A solar-powered desiccant system dehumidifies the air. Residents also can summon a robotic cooler — imagine an A/C on wheels — to lower temperatures in portions of the house.

-

The tornado safe room (not shown) is designed in accordance with FEMA standards to withstand 250-mile-per-hour winds, and is built to stay intact even if the rest of the house is destroyed.

A Renewable Neighborhood

After the competition, the house will return to UAB for the public to tour. It will become part of a microgrid of four “tiny homes” serving as a model for renewable, sustainable energy use.

“Participating in the Solar Decathlon shows our commitment to sustainability, innovation, and cross-discipline workforce development,” Taherian says. “Once the house is fully set up at UAB, it will show that energy efficiency and innovation are some of our core principles.”

In promoting and raising funds for the project, Morgan met many Birmingham residents interested in using renewable energy for their homes. “My vision is for the house to become a catalyst for green energy in this area,” she says. “This house is built with the environment and people in mind. It’s built for Alabamians.