When Robert Blanton, Ph.D., taught the first Honors College course on human trafficking last spring, he began by introducing his students to the dark nature of the topic—from modern slave labor to sex trafficking.

“We started out by watching a fairly indicative video of how the process works,” he remembers. It followed the stories of international sex-trade victims—women lured away from home under false pretenses and sold into prostitution rings, where they were regularly beaten and brutally raped.

Blanton says many students were in tears before the video ended. And then he shocked them again: Human trafficking isn’t confined to impoverished, far-flung countries, he told them. It happens in Birmingham.

“These are real humans, and these are real things going on,” he said. “Now let’s pull back and figure out how to analyze it.”

Beyond Emotion

Blanton, a professor in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences Department of Government, had touched on the subject of human trafficking in previous classes and was struck that several students chose to do their senior theses on the topic. Their interest was contagious. “This was always a topic I wanted to explore,” he says, “but it was the students themselves who taught me how important an issue it is.”

To develop the original course and a separate Honors College seminar titled Diamonds, Drugs, and Guns, a survey of the illicit global economy, Blanton went beyond heartstrings and headlines to help students understand human trafficking as a global problem perpetuated by numerous complex factors. “You have to get beyond the sheer emotion and examine this as an economic, social, and political phenomenon,” he says. “I tell my students that if they really want to effect change, then they have to know more than the horrible things that go on. They need to know why they happen.”

Through his course and honors seminar, Robert Blanton analyzes the economic, social, psychological, and political underpinnings of human trafficking.

Through his course and honors seminar, Robert Blanton analyzes the economic, social, psychological, and political underpinnings of human trafficking.

Terrible Truths

Tessa Case, a junior from Birmingham majoring in international studies, says that prior to the course, she had a common misperception about the subject created by popular culture. One example is the 2008 hit movie Taken, starring Liam Neeson, in which beautiful, privileged white women are kidnapped and sold into sex slavery. It makes for a dramatic plot—but Case says it only perpetuates a myth.

“You see a movie like that and think crime syndicates drug and kidnap these women,” she says. “That actually got me interested in this subject. But the reality is completely different.” There are places in the world where parents knowingly sell their daughters out of desperation, she says. “There are certain dynamics like that where you have to put your cultural lenses on so that you can understand the root of the problem.”

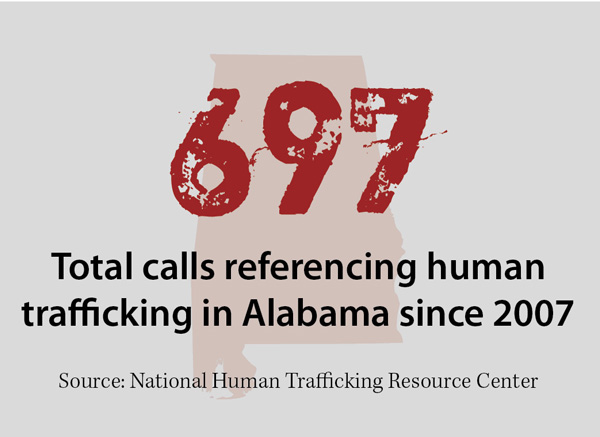

Meanwhile, Case notes that while the sex trade often gets the lion’s share of attention in the media, it’s far from the only form of modern slavery. “While sex trafficking is pervasive, on a global level, there is a lot of forced labor and labor trafficking that makes up the majority of the human trafficking problem,” she says.

The most common form of slavery today is bonded labor, Blanton adds. “That’s where you bring in ‘employees’ to do a job and then essentially take away their free will,” Blanton explains. “You take their passports or papers, or make it physically impossible for them to leave. Then you tell them they owe you a debt, because you brought them there—they have to work to repay that debt. There are situations in India where the debt is passed down from generation to generation, and the kids are born into slavery.”

Holistic Understanding

Though most of the students who enrolled in the new course had heard something about modern slavery, junior Sarah Leffel, an education major from Huntsville, Ala., had actually seen the tragic stories up close. The summer after her freshman year, she went to Thailand to work with an organization dedicated to rescuing women from the sex trade. She recalls many heartbreaking encounters with the women—many of whom become emotionally as well as financially dependent on the very people who exploit and abuse them.

But it took Blanton’s class, she explains, to gain a more holistic understanding of the problem. “At first, when people would speak analytically about it, I would say, ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about. You didn’t experience it,’” Leffel remembers. “But what I learned through the class was even bigger than studying about human trafficking or the sex trade. It was the value in approaching a problem mentally, stepping back from my emotions to be able to process other perspectives.”

(Left to right) Students Sarah Griffin, Sarah Leffel, and Tessa Case came away from the course resolved to combat human trafficking through awareness, education, and the law.

(Left to right) Students Sarah Griffin, Sarah Leffel, and Tessa Case came away from the course resolved to combat human trafficking through awareness, education, and the law.

Close to Home

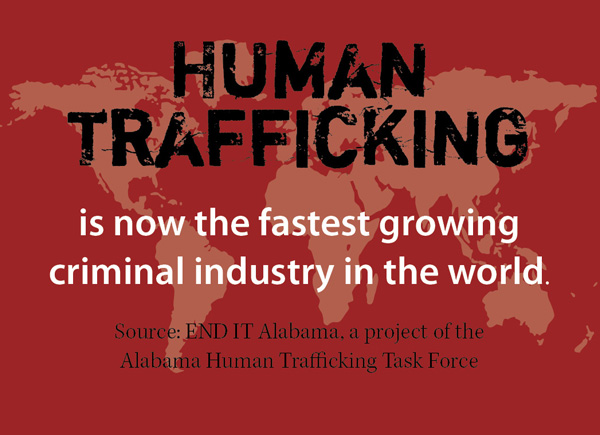

One of the toughest truths about human trafficking for many Americans, including Blanton’s students, is how widespread it is in the United States. Birmingham is part of a sexual-trafficking network along the Interstate 20 corridor that also includes Atlanta, Memphis, Nashville, and Chattanooga. “That’s basically the loop,” Blanton explains, “and Birmingham is a pretty big cog in that wheel.”

Sarah Griffin, a junior from Birmingham majoring in political science and philosophy, remembers her reaction to that as nothing short of shock. “I never knew about this,” she says. “This is my home. How can these terrible things happen here?”

Blanton echoes Griffin’s reaction. “That was one of the things that always amazed me when I first started looking into it,” he says. “It’s close. It’s on Oxmoor Road in Homewood. A lot of people have no idea.” To drive home the point, Blanton invited Tajuan McCarty—founder and executive director of the WellHouse, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rescuing sex-trade victims in Birmingham and throughout the Southeast—to share her experience, which includes being a survivor herself, with students.

Vulnerability and Psychology

The class also discussed numerous examples from other states, from slave-labor camps working in agriculture in South Carolina and Florida to nail salons in New York City that have forced women to work without pay. A modern-day slave can be anyone from an illegal immigrant who doesn’t speak the language to an American teenage runaway seduced by a smooth-talking stranger. The common factor, Blanton says, is vulnerability.

But how do traffickers manage to hold their victims captive, sometimes in plain sight? “It’s a really twisted psychology behind this,” Blanton explains. “Often it’s one part loyalty—a very strong form of the Stockholm syndrome [irrational feelings of empathy toward captors]—one part economic need, and then the other part is fear. They’re afraid of the outside, afraid of the unknown, and afraid that if they leave, they may end up being even worse off.”

To understand how complicated and seemingly intractable human trafficking is, the students did in-depth studies of the different forms it can take and the factors that make it possible. One group focused on the relationship between human trafficking and the “deep web”—huge swaths of the Internet that are hidden from standard search engines and thrive on anonymity. Another studied the practice of slavery by terror groups like ISIS and the Taliban in the Middle East. Still another project was dedicated to human trafficking in and around Birmingham.

Ready to Act

In spite of the dark, often demoralizing subject matter, many students have come away from Blanton’s class—which he plans to offer again—resolved to raise awareness and help combat the problem. Case is doing an internship at Sojourns, a local fair-trade store. “A lot of fair trade is giving people a chance to make a living wage,” she explains, “and that takes away some of the vulnerability factors that help perpetuate exploitation.” She’s also helping to plan an event at the store to raise awareness of sex trafficking. Leffel wants to return overseas and teach English to women who are coming out of sex slavery. And Griffin, who aspires to go into politics and eventually run for public office, hopes she’ll be in a position to support laws that combat human trafficking and protect victims’ rights.

Blanton finds that deeply encouraging. “It’s been heartening to see how motivated they are,” he says. “It’s great to take students who want to make a difference and play some part in giving them the analytic tools they need to better understand the problem.” That knowledge could help them make a real impact—one that could bring hope to the captive, suffering “real humans” at the heart of the issue.