Jennifer Summerlin, Ph.D., has always loved children's books. Perhaps a little more than most people.

As a child, she biked around her neighborhood searching the trees for the dog party from P.D. Eastman’s Go, Dog. Go! When she became a mom, she “performed” Junie B. Jones so convincingly (while reading the Barbara Park series aloud) that one daughter believed Summerlin and Junie were pals.

So you can imagine Summerlin’s glee when she was chosen to help select the Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts for 2019, 2020, and 2021. An assistant professor of curriculum and instruction in the UAB School of Education (and a UAB education alumna), Summerlin is one of seven members of the Children’s Literature Assembly, the committee of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) that produces the annual list. The 30 books they choose include works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry for children from kindergarten through eighth grade.

That’s 30 out of hundreds of thousands—perhaps up to a million—children’s books published each year in the United States. The Notables list, along with other esteemed children’s literature honors such as the Newbery and Caldecott medals, serve as “guideposts” for parents and educators faced with all those options, Summerlin says. “Award winners are considered royalty. You can’t go wrong in giving, recommending, or reading these books to a child.”

Jennifer Summerlin reads about 700 children's books each year to find new favorites.

Jennifer Summerlin reads about 700 children's books each year to find new favorites.What clicks with kids?

Narrowing down the million to a few favorites isn’t easy, but it is fun, Summerlin says. Every week at her house is like a holiday, when surprise packages full of new hardback picture books, chapter books, and novels arrive. Last year, publishers nominated—and sent her—about 700 books in all, and she relished the challenge of attempting to read every one.

As she reads, Summerlin logs each book on gridded pages in a thick binder, making notes and scoring each one using her own complex rating system. The NCTE’s “main criteria are the use of language and style,” with extra points for those that are unique, inventive, and playful, she explains. And there are other factors to consider. Does the book have an appealing format and an enduring quality? Does it meet the characteristics of its genre? Is it inviting to children?

Summerlin has a good idea about the kinds of books kids find irresistible from 12 years of teaching in K–5 classrooms. There she learned that children aren’t concerned with reading levels like parents and educators can be. They simply grab what interests them. “Either it’s funny, or it connects with their lives,” she says. “I try not to underestimate the power of a kid to know what’s good. If they want to read something badly enough, even if it’s not on their level, then they’re going to figure it out.”

For some kids, that includes nonfiction. Summerlin’s students devoured everything they could on animals and the Titanic, and a book on historic plagues kept disappearing from her classroom—a sure sign of its popularity. Other children gravitate toward comics and graphic novels, which incorporate “a lot of complex thought” nowadays, Summerlin explains. As for picture books, they can benefit kids of all ages with their surprisingly rich vocabulary (because they’re designed to be read aloud by adults). “Choosing books other than traditional stories or series doesn’t make kids poorer readers,” Summerlin notes. “All of that is reading.”

Reading, meaning, writing

As Summerlin talks about books, she pulls shining examples from the tightly packed shelves and cabinets in her office. She flips through the pages, making the books come alive in her hands.

Books have the power to open doors, Summerlin says. She reflects upon a favorite quote she shares with UAB students in her course on children’s literature: “Rudine Sims Bishop, a well-known expert in the field, wrote that books should be a mirror, a window, and a sliding glass door,” Summerlin says. That means “all kids should see themselves reflected in literature. It should be a window into other worlds. And it should empower them to act—to walk through that door.” The books that accomplish that earn positive marks in Summerlin's ratings binder.

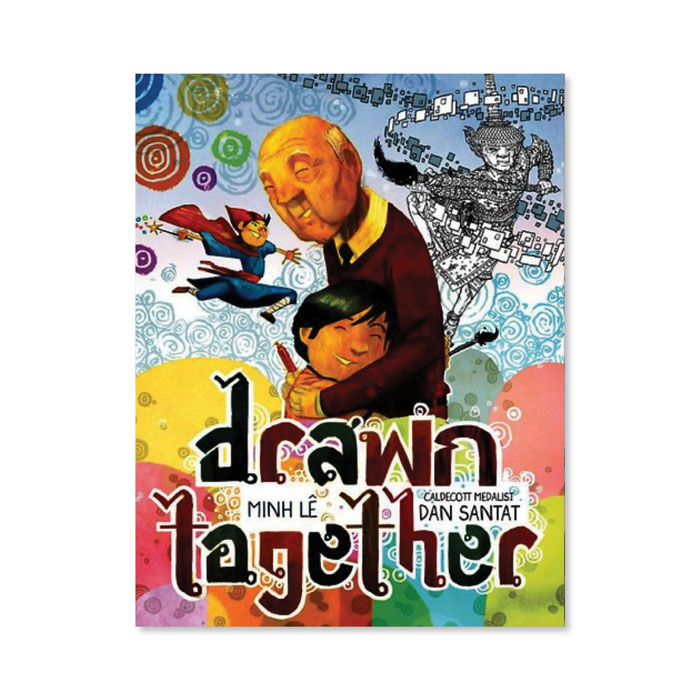

She points to Drawn Together, a selection on the 2019 Notables list, as an example of a book that nails the trifecta. In the beautifully illustrated story, a child and grandfather in a Vietnamese-American family learn to leap language barriers through art. Summerlin is excited to see more diverse readers reflected in the books on the Notables list, though “we’re still not where we need to be,” she says.

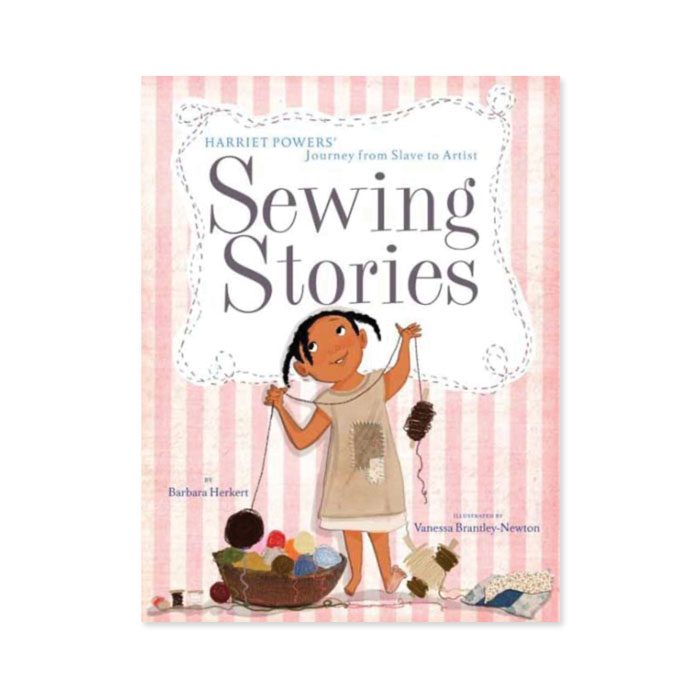

At the same time, Drawn Together gives other children a view into a different culture, remaining respectful and authentic without resorting to bias or stereotypes. Other books offer a window into history, emotions, or social issues. Two examples are Sewing Stories—the true story of a Georgia woman born into slavery who became a well-known artist—and Dreamers—which explores a parent’s difficult decision to immigrate to another country for the sake of a child’s future. Summerlin loved sharing stories like these with her students.

“Thinking about how a character deals with an issue in a book creates a way to have deep conversations in the classroom that aren’t personal,” Summerlin says. Books provide a way for children “to uncover big themes for themselves and think about the world as a bigger place. It helps to build community.”

Quality literature also helps to build a new generation of independent thinkers ready to step through Sims Bishop’s sliding glass door. Summerlin encouraged her young students to read books and then write their own. “Good reading and good writing go hand in hand,” says Summerlin, who wrote stories herself as a child. “Children will evaluate a book for the meaning and then dive into it to see the author’s techniques. They want to see what makes it good and how they can use that in their own writing.”

A year in the making

Once Summerlin and other members of the Children’s Literature Assembly submit their picks for the top 30, they meet at the annual NCTE conference to review the first draft of the Notables list. That’s also their opportunity to sell each other on books they loved that didn’t make the initial cut. “It’s a little justification, a little bartering,” Summerlin says with a laugh. After some rereading and another draft list, the group meets again at the annual Tucson Book Festival to make final decisions on the top 30. The entire process—from initial book deliveries to release of the Notables list—takes a full year.

Soon the process begins again, and Summerlin must clear out books to make room for boxes of new candidates arriving on her doorstep. She has a lot of fun giving them away—perhaps as much fun as she had reading them. Some she donates to recent UAB education graduates who are establishing classroom libraries. Others go to the children in her neighborhood, through a small library she has set up in her house.

And every time she gives someone a book, she gets a smile in return. “Kids love books,” Summerlin says. “Even in today’s digital world, if you want a child to settle in, just open a book.”

A surefire solution

Do you know a child who is a reluctant or struggling reader? Summerlin recommends Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Half written, half drawn, and all mystery and adventure, the novel captivated kids in Summerlin’s elementary classroom. “The beauty of the story”—which begins with a child and a mechanical man in a Paris train station—"is unbelievable,” Summerlin says.

* Discover all the opportunities for learning, discovery, and experience in the School of Education.