America’s prisons are packed. The United States has the lowest violent crime rate, yet it has the world’s highest rate of incarceration, and it jails criminal offenders for longer periods than any other industrialized country. That has led to a national epidemic of overcrowding. Alabama’s prison system, in particular, has been on the verge of a federal takeover due to overcrowding and issues related to it—including the sexual abuse of inmates.

Martha Earwood’s Community Corrections course explores innovative solutions that can help the criminal justice system reduce these problems. But our attitudes are the first and most important thing that must change, she says. The average person gives prison overcrowding and its effects on inmates little thought and less sympathy. “We are stuck in our stereotypes of ‘you did the crime, now do the time,’” explains Earwood, assistant professor in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences Department of Justice Sciences.

So Earwood developed service-learning projects that take her students inside prisons and courtrooms to get a glimpse into the lives of inmates and other criminal offenders. Interacting with a part of society that is feared and ostracized can shift perceptions and inspire a desire for action, she says.

The projects also introduced students to programs that are already working to improve the system. To ease overcrowding, governments must send less people to prison—or choose alternatives that go beyond probation or parole supervision. Such community-based corrections programs do well even in “tough-on-crime” states like Alabama, Earwood says, because they can help lower the chances that participants will commit future crimes and return to prison.

Bonds Through the Bars

Sophomore sociology major Lyric Sanders admits that she was a little nervous before walking into the Birmingham Work Release center to see one of these programs in action. But her feelings changed once she met the inmates. “I was shocked—hearing them talk about their children and grandchildren, you realize that they are just like everybody else,” Sanders says. “I realized that not everyone with a jail record is a tough, hardened criminal. They had just one thing in their lives that went wrong.”

Sanders was among a group of students who visited the work release center and the Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women in Wetumpka to record short video messages from inmate mothers to their children. Carol Potok, executive director of the nonprofit group Aid to Inmate Mothers (AIM) helped open the doors of these facilities to Earwood and her students. One of AIM’s most successful initiatives, known as Storybook, records mothers reading books to their young children. Each child then receives a DVD of that video with a copy of the book his or her mother read. Inspired by Storybook, Earwood developed the student service-learning project to provide a similar outlet for inmate mothers with older children who want to send messages about things like missed birthdays and holidays. “All those holidays we take for granted are painful for people who are separated from their families,” Earwood says.

“The research is unrelenting that maintaining relationships with key family members is a way for people to be successful when they leave prison,” Earwood adds. “That adjustment is huge, and if your relationships have remained intact, then you have a better shot.” Such programs also can improve the behavior of women while they remain in prison, Earwood adds.

Some of the mothers supplemented their videos with notes and drawings. “Color is something you miss in prison,” says Earwood, who supplied the inmates with colored paper and pens. One woman asked students to record her singing a song and playing the piano.

The personal nature of the messages “made the students see the measure of what the inmates had lost,” Potok says.

Mother to Mother

Sanders and her classmate Patricia Goldsmith, an honors student double-majoring in sociology and criminal justice, took that loss to heart—perhaps more than some other students, because Goldsmith is Sanders’s mother. The two discussed how being separated by prison walls would affect them both. Sanders says she would struggle greatly if she didn’t have her mother around.

“These inmates look like your kids, your mother, or your grandmother,” Goldsmith says. “We kept talking about how sad it is that we can’t fix things for them right now.” She does hope that more people, regardless of major or profession, will take a course like Earwood’s Community Corrections class and support programs like AIM. After all, 80 percent of the inmates eventually will be released, and everyone should want to help them succeed, she says.

With five children of her own, Goldsmith spoke to the inmates mother-to-mother. When some got so emotional that they wanted to stop recording their messages, Goldsmith encouraged them to take a break and then finish—not only for their children but also for themselves. “I knew they would feel bad for quitting,” Goldsmith says. “It was heartbreaking in a lot of ways, but I felt good that everyone got a video out.” The students created a total of 182 videos at both sites.

Second Chances

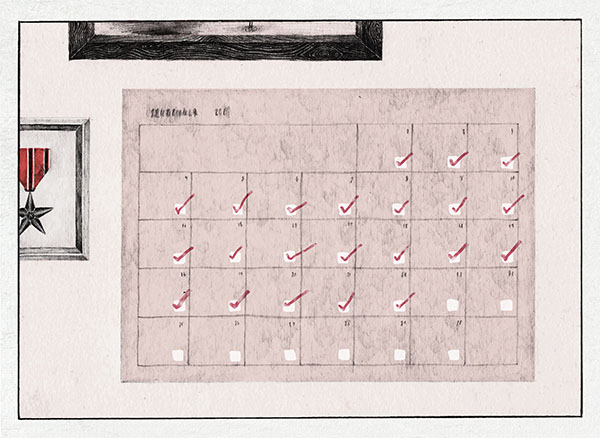

A couple of years ago, Shelby County tried something new for Alabama—Veterans Court, an alternative sentencing program that gives men and women who have served in the military a chance to stay out of prison. Available to veterans who have committed low-level, not excessively violent crimes, the court requires participants to complete a rigorous, yearlong series of classes and regular drug screenings—or else face prison time.

For their service-learning project, a group of Earwood’s students created a documentary-style video to help Judge William H. Bostick spread the word about Veterans Court to community groups or other counties considering a similar solution. The concept is becoming more popular nationally, and with good reason, Earwood notes. “It’s a great way to keep people out of prison,” she says. “The students saw that connection—veterans are keeping their jobs, they’re paying their bills, they’re paying their child support. It’s much healthier.”

Criminal justice major Eric Glaves, a Hoover resident who was a junior during the video project, says some participants entered the program just to avoid a jail sentence on their records, but in the end, they respected how that second chance helped them. “It’s not a get-out-of-jail-free card for the veterans who are participating,” he explains. “They have to work hard. It’s not an easier version of regular court.”

Earwood says the one-year commitment is perhaps more difficult and time consuming than a prison sentence for many offenders. “Judge Bostick had no hesitation to lock up people immediately if they failed a drug screen,” she says. “Students were surprised.”

Bostick’s personal interaction with the participants helps to make the program work, Glaves says. “Judge Bostick opens court by talking with each of the offenders individually. He asks about their lives, and that creates mutual respect.” In addition, other veterans act as mentors, or Alcoholics Anonymous-type sponsors. They never miss a court date and are vital to the program’s success, Glaves says, because the veterans share a bond with one another. Often it’s the mentors who can encourage the offenders to open up and talk.

Above all, Glaves was struck by the similarities between himself, people he knows, and the people in the court. “Not all criminals are inherently bad,” he says. “They are human beings who can change.”

Enhancing Justice

As Earwood had hoped, the service-learning projects have inspired students to consider working toward improving the criminal justice system. Sanders plans to use her sociology degree to pursue research quantifying the success of community corrections programs, specifically their effects on inmates’ children, who often end up in the system themselves. Such research could lead to more funding for these programs, Sanders notes. Glaves would like to see the Veterans Court mentorship concept spread, even to standard criminal courts. “That would help a lot with recidivism rates,” he says.

“My students are the next generation of policy makers, and they have seen something that average citizens don’t,” Earwood says. “They know how community corrections programs work and the impact they make. We’re not saying that we should be devoid of justice or consequences, but we’ve got to think about these things differently if we’re going to prevent prison overcrowding. We can figure out better ways of punishing people.”

• Learn more about the classes and degrees offered by the UAB Department of Justice Sciences.