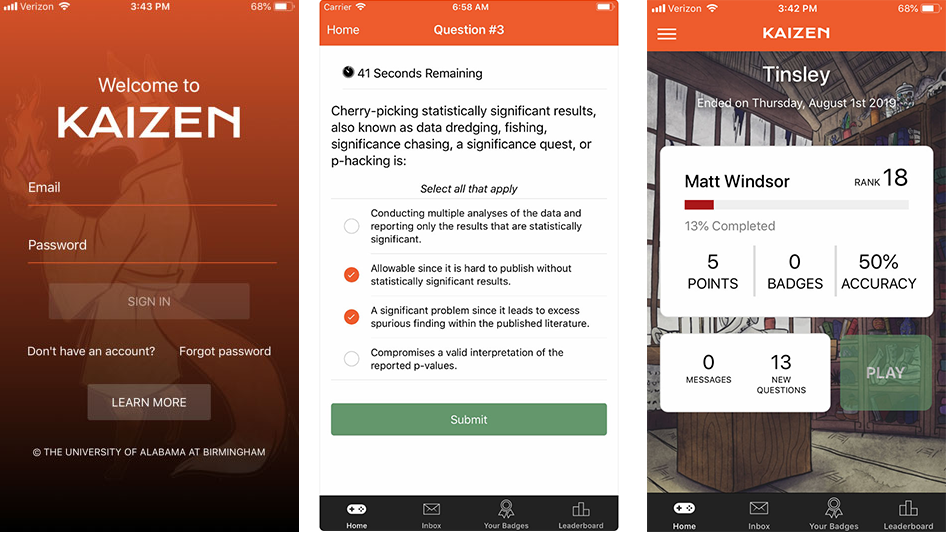

Statistical significance and experimental design may not be the most exciting topics, but the R2T Kaizen game keeps them lively with quick-hit lessons and plenty of game elements, including badges and a live leaderboard showing who answered the most questions correctly. "You could see other people moving around the leaderboard and that definitely appealed to me," said postdoctoral researcher Brandon Roberts.

Statistical significance and experimental design may not be the most exciting topics, but the R2T Kaizen game keeps them lively with quick-hit lessons and plenty of game elements, including badges and a live leaderboard showing who answered the most questions correctly. "You could see other people moving around the leaderboard and that definitely appealed to me," said postdoctoral researcher Brandon Roberts.

On a recent summer evening, while the rest of the world was obsessing over the War for Winterfell on Game of Thrones, muscle biologist Brandon Roberts, Ph.D., queued up a different kind of video.

It may not have had the visual punch of a dragon duel, but this short film promised to help him fight his own worst instincts in the lab. Plus, there was a Texas sharpshooter.

The Texas sharpshooter is one of the brief cautionary tales that biostatistician David Redden, Ph.D., shared as he covered common ways scientists fool themselves — and how they can stop. (See “Don’t get fooled,” below.) Roberts, who is in the final stage of a postdoctoral fellowship at UAB, gave the video his full attention.

That was partly because of the subject matter. Like every young scientist with a K or T training award from the National Institutes of Health, Roberts is required to complete training in four areas: scientific premises, authentication of key biologic resources and chemical reagents, relevant biological variables and statistical rigor. Redden’s lessons checked that box. They also promised to come in handy for the rest of Roberts’ working life in the lab. A clear grasp of statistical rigor and experimental techniques now is a required element of all NIH research grant proposals — and continued funding success makes or breaks a biomedical scientist’s career.

‘It’s a course, but also a game’

But Roberts had a more immediate concern: winning.

He is one of more than 250 scientists nationwide who have taken part in a UAB-developed online course known as R2T. Rigor, Reproducibility and Transparency, to give it its full name, uses bite-sized lessons and game elements to increase engagement in these important but fairly abstract topics. As Roberts watched, some other young researcher in Birmingham — or New Orleans, or Ohio — was probably playing the video as well, and getting ready to ace the multiple-choice questions that would appear onscreen when it ended.

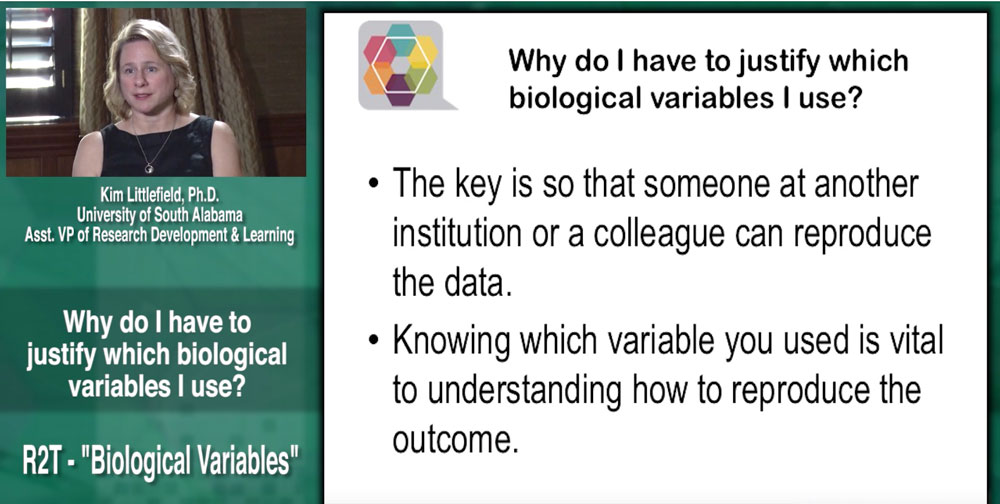

In the R2T training modules, subject experts from UAB's CCTS Partner Network explain key learning points and answer common questions in brief videos.

In the R2T training modules, subject experts from UAB's CCTS Partner Network explain key learning points and answer common questions in brief videos.

“R2T is a course, but it’s also a game,” said Redden, vice chair of the Department of Biostatistics and co-director of the Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Research Design (BERD) unit of UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science. “As soon as the question appears a timer starts; the quicker you are, the more points you get.”

Those points show up instantly on a community leaderboard. That gave Roberts instant feedback on whether or not he was grasping the material — and where he stood in relation to his classmates. (Players can choose to use their own names or an alias on the leaderboard.) And he wasn’t about to be left behind.

Register now to play R2TThe next season of Rigor, Reproducibility and Transparency training from the UAB CCTS starts Sept. 9 and runs through Oct. 9. Register online today. UAB players who complete the course have that fact recorded automatically in the university’s LMS system. |

“I grew up gaming,” Roberts said. “I was a little bit disappointed when I would finish the quizzes and have anything less than 100 percent. You could see other people moving around the leaderboard and that definitely appealed to me.” Those game elements and the modular nature of the course helped nudge Roberts to carve out time in his hectic schedule. “I have lots of experiments going on, meetings, job interviews,” he said. “But between those things you get gaps of 30- to 45 minutes. It’s easy to read a paper or watch a video with some headphones and then take a quiz.”

‘Taken on a life of its own’

Welcome to the world of R2T, a month-long, self-directed course that launched at UAB in 2016 and has since spread around the country. “It’s taken on a life of its own,” Redden said. “We did an initial pilot, and I personally thought after all these years of teaching that people wouldn’t care about this team stuff and point systems. But they love it.”

To date, “we’ve had 265 people play the game at 15 institutions,” Redden said. “We’re currently running a 52-person game at Vanderbilt University, and we’ve got a game in design with Ohio State University. We’ve presented this at national conferences, and we’re getting pressure to take it nationwide.”

Rigor and reproducibility have been hot topics in science for most of the past decade, following several high-profile studies in which subsequent researchers couldn’t replicate previous work. (See “What’s the problem?” below.)

In a now-landmark commentary in the journal Nature in 2014, National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., and Principal Deputy Director Lawrence Tabak, DDS, Ph.D., pledged that the NIH would take action to address the situation. With rare exceptions, they noted, “we have no evidence to suggest that irreproducibility is caused by scientific misconduct.” Instead, Collins and Tabak explained, it was a lack of understanding in the vast majority of cases — poor training in experimental design, including “blinding, randomization, replication, sample-size calculation and the effect of sex differences.” The NIH introduced a requirement that, as of January 2016, all new investigators receiving NIH funding needed rigor and reproducibility training.

A wonderful opportunity

“We knew this would greatly affect the way we trained young scientists and approached getting federal funding,” Redden said. He and Jennifer Croker, Ph.D., senior administrative director of the UAB CCTS, took on the challenge of providing that training. “We said, ‘We need to make sure everyone knows this is coming and connect them with tools and resources to be successful,’” Croker said.

They developed a lecture series, with presentations by content experts from the 11-member CCTS Partner Network, which includes UAB, Auburn University, the University of Alabama, the LSU Health Sciences Center and other institutions in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. The classes were well attended, but inherently limited by space and schedule constraints, Croker said. Focus groups also revealed that attendees recognized the importance of the information, “but they felt it was kind of dry,” she added.

So Croker and Redden turned to a proven winner: Kaizen, an online gaming platform developed in the CCTS in the early 2010s by James Willig, M.D., a physician and informatics specialist at UAB. “We knew about Kaizen and have a close relationship with James,” Croker said. “We thought this was a wonderful opportunity.”

“It’s pretty onerous to teach this material,” said Willig, an associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases and assistant dean for clinical education at the School of Medicine. “Kaizen takes that away — the burden of finding a venue, scheduling people — that’s gone.” Plus, there was Kaizen’s secret sauce, an emotional component that helps busy people focus on learning abstract concepts such as inter-operator variability or raw dataset archiving. Willig summarizes it like this: “No way my friend is going to beat me.”

Kaizen is designed for bite-sized learning. Its creators recently introduced apps for Apple and Android smartphones. (The screenshot at right demonstrates the author's difficulty with internal medicine questions.)

Kaizen is designed for bite-sized learning. Its creators recently introduced apps for Apple and Android smartphones. (The screenshot at right demonstrates the author's difficulty with internal medicine questions.)

Elevator education

The idea for Kaizen grew out of new residency work-hour rules instituted by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education in 2003. Limiting the hours that young doctors work was a good idea, but it had the unintended consequence of slicing out valuable teaching time, Willig explained.

He knew he couldn’t fit any more formal teaching into the harried lives of his medical residents. They already spend the bulk of their waking hours speed-walking from floor to floor in the hospital as they care for patients. Instead, Willig worked with CCTS programmers on something better adapted to modern medicine. His online quiz platform, which he called Kaizen after a Japanese word meaning “continual improvement,” was essentially a veteran doc in a box.

Willig captured the kind of real-world lessons that he and other experienced physicians pass on to their young charges in hospital hallways and patient rooms. Then he churned them out weekly as sets of mini-case studies, with multiple-choice quizzes after each one. Kaizen was designed specifically for residents to play on their smartphones, a few minutes at a time, while they waited for elevators or in the cafeteria line.

“Bite-size learning,” as Willig called it, solved the time problem. But would they actually play? How could he get his students to devote their energy to an entirely voluntary act of self-improvement? The answer, said Willig, who had dreamed of being a video game designer as a young man, was competition.

“Doctors tend to be competitive,” Willig said. “These are smart people who want to see who is the best.” He captured each player’s success rate on answering questions and built in a leaderboard that all players could see. He gave out silly badges and offered prizes for high scorers. “Everyone has their own motivators,” Willig said. “I think of it like a fishing lure with six or seven hooks on it. I’m not particular about what your motivation is, and I don’t think one is necessarily better than another. I just have to have a platform with enough motivators built in.”

Leading with the data

As Kaizen became a hit in internal medicine, it quickly spread to other UAB medical internship programs, then to the School of Nursing and beyond. The Kaizen training platform now has engaged more than 2,000 players in seven states. Research by Willig and other Kaizen users — seven published papers, with several more on the way, Willig says — also has established a significant link between Kaizen play and exam scores and other outcome measures.

Kaizen’s novelty attracts interest. But its success comes down to hard data, Willig said. “The first thing that gets us into new places, such as Vanderbilt and Ohio State, is curiosity,” he explained. “They look at our CCTS and what we’ve been doing, and they’re interested in this gamification thing. It has become a bit of a buzzword. But they’re also trying to deal with the same issues we are. Their researchers would love a different way to get access to this training material, for example. And Kaizen turns a task that is usually very lonely and a bit of a grind into something where you feel like you’re interacting with other people. It’s a little bit fun. It’s not watching the ballgame fun, but it’s taken an individual drag and turned it into an interactive, team-based activity.”

“When they start seeing the student engagement they’re sold,” Willig added. “The conversation used to begin with the game aspects, but now we lead with the papers. It adds a different tenor to the discussion.”

Research shows that students in the UAB School of Nursing who engage in Kaizen games improve their test scores.

Research shows that students in the UAB School of Nursing who engage in Kaizen games improve their test scores.

A better way to engage

Carolynn Jones, DNP, an associate professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University College of Nursing and co-director of workforce development for the OSU CCTS, heard Willig present on Kaizen at a national Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program meeting. She also got positive feedback from her former colleagues in the UAB School of Nursing. Jones helped Willig and Redden bring the R2T game to Columbus and introduced Kaizen to her own online graduate courses in clinical research, which prepare students for careers in the growing field of clinical research management and regulatory affairs. “Our courses are all 100 percent online and asynchronous,” she said. “As in any course, students have required learning activities and assignments. But I’ve found that students are often emailing the instructor questions that are answered in the readings — they are winging it and going right into the assignments without reading and digesting content first. I saw Kaizen as a way to better engage online students in the course content.” Questions from the game got students engaged in the assigned readings and lectures, she explained. “We made playing the game optional and for those who wanted to do the game, if they made a certain grade across the board, they could waive the final exam,” Jones said.

As a researcher herself, Jones wanted to test out Kaizen’s effect on her course. So she got OSU’s institutional review board to approve an analysis of student grades based on that initial implementation. And while the analysis is ongoing, early results have demonstrated an improvement in test scores. Plus, “it’s great fun,” she said. She has developed a second game to address the requirement for good clinical practice (GCP) training for clinical research, a recent NIH mandate. The GCP Kaizen game is designed to provide real-life scenarios and application of the GCP guidelines for best practices and compliance in clinical research. Students played as individuals and in teams, and Jones chose a Winter Olympics theme, with digital badges based on speed skating, skiing and other winter sports events and the teams as individual countries. “When I would push out an announcement of the leaderboard, I would fly the flags of the top three scoring countries. At the end of the semester, we featured the top three countries, based on group scores, flying the flags and including the audio national anthem as closing ceremonies. We just had an open house four our students, and I brought Olympic medals to give out.

“Teaching, and taking, an online class can be boring, without that human interaction,” Jones said. “Kaizen helps us build connection. And it’s a true collaboration between universities, as these CCTS projects should be. “We anticipate several collaborative publications out of this work and hope to be able to share the game broadly after we test game improvements during the autumn semester.”

To the clinic and beyond

Meanwhile, faculty and clinicians at UAB continue to push the boundaries of Kaizen. Michelle Talley, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the School of Nursing, has tested a Kaizen game with patients in her pediatric diabetes clinic. While they wait for their appointments, the patients answer questions on an iPad with the goal of boosting their knowledge of how to manage the disease. Results have been promising, Willig said, with a paper due to be published soon.

“I had this little bitty idea, and everyone else has thought of a better way to use it,” Willig noted. “Redden said, ‘We could use this for R2T,’ Michelle Talley said, ‘We can do this with patients.’ Everyone has their own ideas, and it’s a ton of fun.”

Brandon Roberts agrees. The R2T training was “very appealing,” he said. Generally, as soon as a new set of material and questions was released, “I had it done in a day or two.” The concepts embedded throughout the course were valuable, he added.

“Some of this is new information for the learners, some is review, but in either case we specifically try to use concrete examples,” Redden said. “When we train biostats students here at UAB about statistical power, for instance, we tell them, ‘Too few is wasting resources and wasting people’s time. Too many is also wasting resources and delaying progress.’ How do you find that balance? That’s the kind of real-world question we cover.” As NIH guidelines change, the course is continually updated, Redden added.

Roberts is happy to recommend the experience. “I think it should be something that all students — undergrads, graduate and postdocs and probably even early-career scientists — should participate in and enjoy.”

Register now to play R2T

The next season of Rigor, Reproducibility and Transparency training from the UAB CCTS starts Sept. 9 and runs through Oct. 9. Register online today.