Josh May, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Philosophy, combined a fellowship and a sabbatical to spend more than two years exploring neuroscience research, taking classes and joining the lab of UAB's Rajesh Kana, Ph.D. That research informs May's book, "Neuroethics," which was named one of the top 10 academic titles of 2024.Philosopher Josh May, Ph.D., is interested in nuanced responses to moral controversies. For a decade, he has taught a popular course on neuroethics, a field that has developed since the beginning of the 21st century to study the moral issues raised or addressed by discoveries in neuroscience. For example: Are pills and brain stimulation appropriate methods of moral improvement? Should we trust brain science to read the minds of criminals? Does neuroscience show that free will is an illusion? Does having a neurological disorder exempt one from blame?

Josh May, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Philosophy, combined a fellowship and a sabbatical to spend more than two years exploring neuroscience research, taking classes and joining the lab of UAB's Rajesh Kana, Ph.D. That research informs May's book, "Neuroethics," which was named one of the top 10 academic titles of 2024.Philosopher Josh May, Ph.D., is interested in nuanced responses to moral controversies. For a decade, he has taught a popular course on neuroethics, a field that has developed since the beginning of the 21st century to study the moral issues raised or addressed by discoveries in neuroscience. For example: Are pills and brain stimulation appropriate methods of moral improvement? Should we trust brain science to read the minds of criminals? Does neuroscience show that free will is an illusion? Does having a neurological disorder exempt one from blame?

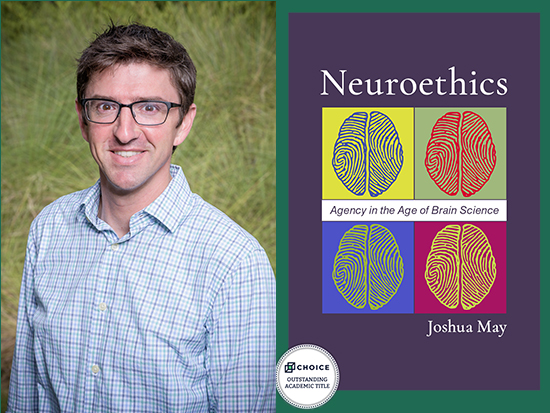

May, a professor in the UAB Department of Philosophy, offers his answers to those questions and many more in “Neuroethics: Agency in the Age of Brain Science.” He describes the book as a “highly opinionated tour” of the intellectual issues being raised on the “new frontier of brain-based technologies,” as well as the lessons that “neuroscience is telling us about ourselves.” “Neuroethics” was selected as one of the Top 10 Outstanding Academic Titles of 2024 by Choice Reviews, the publishing unit of the Association of College and Research Libraries.

That recognition was “really gratifying,” May said. “My goal for the book was maybe overly ambitious. I wanted to write an introductory text that is also advanced and contributes to the literature.” The Choice Reviews honor “made me feel like it achieved those goals,” he said.

To write “Neuroethics,” May spent two and a half years during the pandemic immersing himself in the latest neuroscience research, thanks to a prestigious fellowship from the John Templeton Foundation, which he combined with a UAB sabbatical. In addition to extensive reading, May’s process involved “taking all the classes needed to get a Ph.D. in behavioral neuroscience without getting the degree,” May said. He also joined the lab of UAB Professor Rajesh Kana, Ph.D., who studies autism using neuroimaging in the Department of Psychology. “This project really drew on the UAB community,” May said.

We asked May to share some of what he learned through the project:

1. There is no typical brain

Neuroscience studies, and most people, tend to distinguish between people with brain diseases, or mental disorders, and the neurotypical — in other words, “everyone else.”

But it turns out that brains are more like fingerprints than opposable thumbs, May says. They are not some standardized part of the human repertoire that is defective in a subgroup of people. Instead, they are in many ways unique from person to person.

“My sense is that in neuroscience there has been a move to appreciating differences in brain activity,” May said. “Neuroimaging studies show that there is wide variation in the general population’s brain activity during memory recall, emotional responses, sleep cycles — you name it.” Researchers necessarily have to group people together in studies, “to look at averages, like we always do in science,” May said. “But when researchers look at individual differences, they see plenty of variation among ‘neurotypical’ people on the very same task.”

“Neuroimaging studies show that there is wide variation in the general population’s brain activity during memory recall, emotional responses, sleep cycles — you name it.”

2. We’re all on some spectrum

People have become familiar with the idea that autism is, as it is now known, autism spectrum disorder. Some individuals have high support needs. Others may exhibit unusual behavior in certain situations, and still others may not appear any different from “normal.”

“I think we need to stretch that picture,” May said. “There is a spectrum for all aspects of cognition,” and our places along any spectrum are not fixed, he argues.

“Like neurotypical people, individuals with autism, Alzheimer’s, major depression and other conditions have good days and bad days, as well as fluctuations throughout the day depending on circumstances and triggers,” May writes in “Neuroethics.” Autistic individuals may react “when they experience changes in routine, sensory overload, etc.,” May continues. “Similarly, a series of grueling meetings, subtle slights and a traffic jam can cause a neurotypical person to fly off the handle. Stressors, anxieties and cognitive distortions vary across individuals and time, but they all can tax our nervous systems and ultimately our agency.”

May’s experience in Kana’s autism lab was intellectually transformative. “Rajesh was key in helping me realize that the field had been looking for a clear autism biomarker for a long time, but nothing substantial has been found. The thinking was that there should be some sort of neurobiological mechanism that would allow us to identify autism and get to quicker diagnoses, especially for kids. But brains are so variable that there might not be one single neural signature for a spectrum.”

May’s time in Kana’s lab also led him to be more aware of the growing neurodiversity movement among individuals with autism and other neurological differences. “They are really pushing against the idea that neurodivergence is something that necessarily needs to be fixed. Some autistic people say, ‘This is part of my identity,’ while others seek treatment. I have been thinking a lot about those two different perspectives and trying to reconcile them. Certainly, we need more acceptance and understanding.”

The role of unconscious processes in our lives “concerns people,” May said. “They say, ‘If my brain’s on autopilot, I am not in control. I am the conscious part of my mind.’” May thinks this is a mistake.

3. Free will exists — it’s just different

From neuroscience research, “we are learning that our actions are often driven by unconscious, automatic brain activity,” May said. A famous study example, which May describes in his book, involved asking participants to move their wrists while they were hooked up to an EEG machine monitoring their brain waves. Hundreds of milliseconds before their conscious decision to do so, the EEG recorded unconscious activity in their brains. The unconscious initiation, in other words, preceded the conscious thought. That study has been replicated in various settings. Other examples of unconscious or automatic brain activities that May cites include sleepwalking (which can involve complex actions) and the fact that you can drive home from work, responding to traffic, while completely absorbed in your own thoughts.

Extrapolating from these findings, free will looks like an illusion to some philosophers and scientists, such as Robert Sapolsky, the renowned Stanford neuroscientist. May disagrees.

The role of unconscious processes in our lives “concerns people,” May said. “They say, ‘If my brain’s on autopilot, I am not in control. I am the conscious part of my mind.’” May thinks this is a mistake. “We shouldn’t just identify ourselves with the conscious part of the mind,” he said. Playing on a lyric from Bob Dylan, he added: “We contain multitudes.”

May uses the analogy of a corporation. Many people think of CEOs, especially high-profile CEOs such as Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, as directing every detail of the companies they lead. “But their special control is limited,” May said. Just like a corporation, a mind “is a very complex thing, with a lot of middle managers,” he pointed out. “Unconscious forces are part of what it is to manage a life. We can indirectly shape these unconscious forces in the same way a CEO can influence the actions of a corporation through the managers.”

Or, as May writes in “Neuroethics”: “Jeff Bezos isn’t Amazon, and your conscious mind isn’t all there is to you. You and I are whole organisms, just as Amazon and Apple are whole organizations that extend well beyond their executives.”

“One of the greatest benefits of that fellowship was going back into the student role and sitting in on classes. I got to see other people’s teaching and what seemed to work,” May said. He has since added an experiential learning assignment to all of his classes.

4. To achieve your goals, reshape your environment

Indirect control can have benefits. A simple, well-worn — and very effective — way to stop eating junk food “is just to keep it out of the house,” May said. That works much better than “sitting there, exerting your conscious will” to avoid a bag of potato chips on the counter. “We can shape our environment to achieve our goals,” May said. Another example: Deleting social media. That is what one student in his neuroethics class did as part of a new assignment that May has added to the course based on his Templeton fellowship.

“One of the greatest benefits of that fellowship was going back into the student role and sitting in on classes. I got to see other people’s teaching and what seemed to work,” May said. He has since added an experiential learning assignment to all of his classes, “so that the students can make the class relevant to their own lives,” he said. “They may never have brain implants, but they can apply ideas from the class to adopt a new habit or break an existing one.” His students have tried to quit smoking, stop drinking, set new boundaries with their friends and more. “I got an email from a student recently saying, ‘I just wanted to tell you that I have still been applying the tools from ‘Neuroethics,’” May said. “That made my day.”

“Ethicists commonly stake out one of two extreme positions,” May writes. “Either they defend an alarmist fear of the new frontier or a hubristic futurism that too eagerly seeks a radical transformation of human nature and society. The truth is somewhere in between.”

5. “Nuance” does not mean “nothing”

May concludes his book with a chapter offering five principles for nuanced neuroethics — concepts to keep in mind when confronting any novel, morally charged neuroscience discovery or brain-altering technology. The first is humility, which he summarizes as “avoiding alarmism and neurohype.”

“Ethicists commonly stake out one of two extreme positions,” May writes. “Either they defend an alarmist fear of the new frontier or a hubristic futurism that too eagerly seeks a radical transformation of human nature and society. The truth is somewhere in between.”

May’s emphasis on nuance is not limited to neuroscience. He and a colleague at Boston University, Victor Kumar, just finished writing a book about reducing meat consumption in response to the ethical and environmental issues raised by large-scale industrial farming.

“The debate is framed as ‘Should you be a vegetarian or vegan, or should you just eat whatever you want?’ But studies show that the vast majority of people who try vegetarianism quit,” May said. “They find themselves socially isolated and struggling to learn how to make a strict diet work for their health conditions.”

That does not mean the only alternative is to do nothing, he adds. “There is a growing ‘reducetarian’ movement of people who still eat animal products sometimes but try to reduce their consumption to get away from farming that is terrible for animals, humans and the environment. Our book makes the case that reducing is morally defensible and that psychologically it’s the best way to make lasting change.”