Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., director of UAB’s Center for Addiction and Pain Prevention and Intervention, was part of an expert committee convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engingeering and Medicine to study the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act.

Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., director of UAB’s Center for Addiction and Pain Prevention and Intervention, was part of an expert committee convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engingeering and Medicine to study the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act.

As the toll from drug-involved overdose deaths in the United States continues to climb, an expert committee has released its final evaluation of one of the federal government’s signature efforts to address the opioid epidemic.

The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2016. CARA, as it is known, was the first major federal addiction legislation in 40 years, with provisions to expand prevention and education efforts, increase the availability of the anti-overdose drug naloxone, provide evidence-based treatment and intervention programs, and strengthen prescription drug monitoring.

Two years later, SAMHSA — the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine evaluate the success of its four CARA programs: Building Communities of Recovery, State Pilot Grant Program for Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women, First Responder Training, and Improving Access to Overdose Treatment.

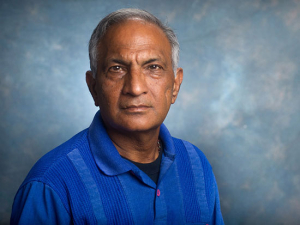

The expert committee convened by the National Academies included UAB’s Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., Kathy Ireland Endowed Chair, professor of psychiatry in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, and director of the UAB Center for Addiction and Pain Prevention and Intervention, or CAPPI. The committee issued a first consensus study report in 2020, a second in 2021, and its third and final report in March 2023.

The legislators who passed CARA were particularly interested in understanding the impact of the services provided by CARA’s programs, and the $181 million in annual funding being spent on them. But as the committee explained in its second report, it could not “determine whether the CARA programs have had a positive impact due to a lack of systematic, quantifiable or descriptive data.”

COVID, culture and structural factors limited impact

By the time the committee convened to study the programs, many of the SAMHSA grants had already been awarded, and the data that grantees were required to collect was not conducive to rigorous research evaluation, Cropsey explains. “SAMHSA grants are service grants focused on education or delivering services,” she said. “The organizations that receive the awards are community-based and often not familiar with research procedures. If they receive 1,000 naloxone kits, they are going to start handing them out. They do not have the staffing or culture for the tracking and data collection that research requires.”

“We need better systems in place to ask these questions about cost-effectiveness and impact that Congress wants to answer.”

—Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., Kathy Ireland Endowed Chair, professor of psychiatry in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, and CAPPI director

Soon after CARA passed, the focus of the opioid epidemic shifted from prescription-drug opioids to much more potent synthetic opioids. And then, in 2020, COVID hit. “There were these two crises that significantly affected CARA programs,” Cropsey said. “There was the surge in opioid overdoses brought on by fentanyl and adulteration of fentanyl across all the drug supply, and then layered on that was COVID, which disrupted all of life.” While much of the health care system pivoted to telemedicine, “administering naloxone or training people to administer naloxone is something that we traditionally have not done remotely,” Cropsey said.

In their final report, Cropsey and her fellow committee members shared their analysis of the factors that, as they wrote, “may have limited the ability of grantees to impact the substance use disorder epidemic.” In addition to fentanyl, COVID, and data collection/staffing factors, the committee noted that structural and policy barriers not addressed by CARA grant programs limited impact. These included inequitable access to medical and social services, the criminalization of substance use disorders, stigma, and the lack of funding and reimbursement opportunities for substance use disorder work.

Looking to the future

How could this situation be improved in upcoming programs? The committee included two recommendations “that can be applied to future program development and evaluation efforts of federal programs broadly,” they wrote.

The first recommendation is that “Congress, when mandating evaluations, confer with the implementing agency and evaluation experts to align expectations with feasibility and resource considerations,” the committee said.

Their second recommendation is that “Congress consider whether the implementing agency has the capacity, mission and culture to (a) oversee the evaluation and, (b) where applicable, support grantees in collecting and sharing data.”

In short, “we need better systems in place to ask these questions about cost-effectiveness and impact that Congress wants to answer,” Cropsey said.