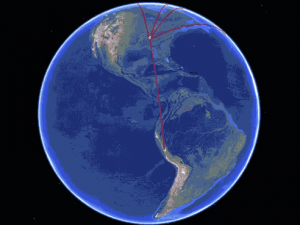

Take a Google Earth tour of the five locations where UAB researchers will work

with their pilot grants from the Sparkman Center for Global Health.

The Tamil word for baby is குழந்தை. In Arabic, cancer is سرطان. The nameless dread that comes when you’re worried about your child’s life — or your own — needs no translation. But it cries out for answers.

Every day, patients in Alabama benefit from the research and clinical expertise at UAB. By extension, people around the world benefit as these innovations spread. But sometimes the process happens much faster. Five young UAB investigators are translating proven methods directly from Birmingham to locations around the world through a new pilot-funding initiative from UAB’s Sparkman Center for Global Health. Their results then could be applied to improve health in the United States as well.

The $20,000 awards, announced in June, are designed to help young investigators escape the Catch 22 that often derails innovative international projects, noted program director Anna Helova, MPH. “Early career investigators often have really great ideas but find it difficult to put them into practice,” she said. “Preliminary results are one of the requirements for many NIH grants. However, early-stage investigators often lack funding to generate these pilot data. If they want to work internationally, potentially even more funding is required.” Another expectation is having established collaborations and partners in that other country, Helova added.

The five projects each support the Sparkman Center’s mission of promoting health in less-developed countries. They also are based on proven techniques pioneered at UAB that have a high likelihood of success and represent three UAB academic units — College of Arts and Sciences and the schools of Medicine and Public Health — using a range of approaches, Helova said. The recipients are now starting work around the globe.

Read on to see where these UAB faculty are going — and why.

How do people with disabilities access their cities? This Lima neighborhood is one of three that will be studied by UAB researchers through their Sparkman Center pilot grant.

How do people with disabilities access their cities? This Lima neighborhood is one of three that will be studied by UAB researchers through their Sparkman Center pilot grant.

Peru: Access, inclusion and the freedom of the city for persons with disabilities

PI: Tina Kempin Reuter, Ph.D.

Other UAB participants: co-investigator Courtney Andrews, Ph.D., and Shane Burns, doctoral student in medical sociology and graduate assistant at the Institute for Human Rights

The question: How does the built environment affect social inclusion and health of persons with disabilities in a large city in the Global South? (That is, the southern hemisphere, where the majority of the world’s fastest-growing cities are located.)

Background: Persons with disabilities are “the world’s largest minority group,” explained Tina Kempin Reuter, Ph.D., director of the UAB Institute for Human Rights and associate professor of political science at UAB. More than 1 billion people are estimated to live with some form of disability — 15% of the world’s population — and the numbers are growing steadily as populations age and chronic health conditions become more frequent. The majority of these people live in urban settings, Reuter noted.

Tina Kempin Reuter in Lima. “I’m interested in how we make cities human-rights-friendly and inclusive,” she said. She is working in three Lima neighborhoods to understand needs and gather data that will "change hearts and minds."Peru was the first country in South America to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “the first human rights treaty of the 21st century, and one of the fastest-growing, too,” as Reuter said.

Tina Kempin Reuter in Lima. “I’m interested in how we make cities human-rights-friendly and inclusive,” she said. She is working in three Lima neighborhoods to understand needs and gather data that will "change hearts and minds."Peru was the first country in South America to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “the first human rights treaty of the 21st century, and one of the fastest-growing, too,” as Reuter said.

The convention may be the most visible aspect of a movement to, as stated on its website, view “persons with disabilities [not] as ‘objects’ of charity, medical treatment and social protection” but “as ‘subjects’ with rights, who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their lives.’”

But the distance between that rhetoric and realities in Peru’s rapidly growing capital, Lima, is a different matter. Lima is “representative of other cities in the Global South that have seen rapid growth, increasing inequity, development of slums and informal housing, health disparities and environmental issues,” Reuter wrote in her Sparkman Center project proposal. There still is a strong social stigma in Peru against disabilities, which means the problem is, for most Peruvians, out of the public eye.

What has UAB already done? “I’m interested in how we make cities human-rights-friendly and inclusive,” Reuter said. Much of that is a measure of the built environment itself — are schools, health care facilities, bus stops, parks and restaurants accessible? While Lima remakes itself, how is this affecting people with disabilities? In other words, Reuter said, “as neighborhoods change, is access for people with disabilities a concern?”

The idea came from a project that Reuter conducted in Birmingham, which combined surveys and mapping of several neighborhoods to gather a picture of how people with disabilities were included or excluded by their surrounding environments. The study, conducted in partnership with the Lakeshore Foundation and the UAB Department of Social Work, looked at Five Points South, Norwood, Fountain Heights and Avondale.

The Sparkman Center project also leverages a study conducted by Reuter and students from UAB’s Minority Health International Research Training Program in the School of Public Health. This past year, they surveyed the attitudes of medical students in Peru toward persons with disabilities and collected data from one area of the city.

Innovation: This fall, Reuter and Andrews, a medical anthropologist and research associate in the Department of Anthropology, will travel to Lima to establish projects in three neighborhoods — Miraflores, Lince and Los Olivos — that represent high-, middle- and low-income neighborhoods in the city. “These are mixed-use areas with high-density housing and high-volume foot and vehicle traffic,” Reuter said.

The project will include surveys, interviews and walk audits of 10 representative blocks to assess the safety, comfort and accessibility of a neighborhood. The goal is to determine whether these areas are friendly to someone walking, biking or pushing a wheelchair. “Mapping marathons” will engage community members, including people with disabilities, to collect data, designating areas of access or barriers on shared Google My Maps.

The team will also use the Photovoice method, in which “you give people cameras, or have them use their phones, and ask them to take pictures in their community that symbolize the issue you are studying,” Reuter said. “It’s another way to gain perspectives, to get an idea of what’s on people’s minds.”

Impact: “If we designed renovations or entire cities in a way that’s accessible to all from the very beginning, it’s not a very expensive thing to do,” Reuter said. “Our hope is to influence policies.” The data from the study will be shared with government officials and non-governmental organizations with the goal of demonstrating the scope of the problem and prioritizing areas of greatest need in Lima. Reuter also aims to develop policy recommendations and best practices that can spread to other cities.

Inserting ground-tested data into conversations with engineers and urban planners, as well as politicians, can “change hearts and minds,” she said. “There isn’t any data like this currently available. We want to bring this to the forefront with the people who are involved in the design of cities. By mainstreaming disability, you can really change the situation, because design is power.”

Alexandria is an ancient city. But Egypt has one of the highest rates of early-onset colorectal cancer in the world, with a third of cases occurring in people age 40 or younger.

Alexandria is an ancient city. But Egypt has one of the highest rates of early-onset colorectal cancer in the world, with a third of cases occurring in people age 40 or younger.

Egypt: prevention, culture and relevancy

PI: Lori Brand Bateman, Ph.D.

Co-investigators: Mona Fouad, M.D., Isabel Scarinci, Ph.D.

The question: Can a culturally relevant intervention, implemented by local medical students, move the needle on colorectal cancer screening in Egypt, where early-onset rates are among the highest in the world?

Lori Bateman with Egyptian medical students. She is training them to adapt behavior-based education methods to local culture in order to promote colorectal cancer screening. Bateman's work with existing UAB projects in Egypt has already allowed her to see how international partnerships can "have a significant impact in a low-to-middle income country where resources may be scarce."

Lori Bateman with Egyptian medical students. She is training them to adapt behavior-based education methods to local culture in order to promote colorectal cancer screening. Bateman's work with existing UAB projects in Egypt has already allowed her to see how international partnerships can "have a significant impact in a low-to-middle income country where resources may be scarce."

Background: Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer globally and generally is diagnosed in people 50 and older. It is prevalent in high-income countries where the Western diet is common, and rates of physical inactivity and obesity are high. But Egypt, a low-to-middle-income country, has one of the highest rates of early-onset colorectal cancer in the world, with a third of cases occurring in people age 40 and younger. The disease often is diagnosed at an advanced stage with poor prognosis. Regular screening is one of the most effective strategies to prevent colorectal cancer, but there are no screening guidelines in Egypt. Here, the disease typically is diagnosed only when patients come to the doctor with symptoms.

What has UAB already done? For two decades, investigators in UAB’s Division of Preventive Medicine have demonstrated that laypeople trained as health advocates can increase cancer-screening rates in areas as diverse as Alabama’s Black Belt and Brazilian tobacco plantations. Ongoing work in Egypt led by Preventive Medicine division director Mona Fouad and Isabel Scarinci, associate director for globalization and cancer disparities in the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB, has established relationships with cancer researchers and clinicians at Alexandria University. That includes a National Academy of Sciences/USAID-funded grant to create a Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center for Colorectal Cancer Research in Egypt.

Bateman, an instructor in the Division of Preventive Medicine, already is involved with this project. During previous trips to Egypt, she trained medical students to conduct a series of focus groups with patients and interviews with clinicians to identify barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening. “There was a general lack of knowledge about screening, fear and anxiety about the invasiveness of screening methods as well as concern about what they would do if they didn’t have the money for further treatment,” Bateman said.

Innovation: The researchers will build on this prior work to develop a culturally relevant intervention focused on promoting colorectal cancer screening among individuals age 30 and older, Bateman said. They then will train medical students from Alexandria University to deliver the intervention in a local primary care clinic. “In Egypt, medical students don’t get a lot of behavior-based education,” Bateman said. “We want to see if we can make an impact on that as well.”

Participants will be provided with a non-invasive screening test (fecal occult blood test or FOBT), along with education about the importance of screening for prevention and early detection. Participants with abnormal results will be referred for follow-up testing and treatment. The intervention’s primary outcome will be a measure of the increase in screening rates among participants.

Impact: Bateman originally trained as a registered dietitian before earning her doctorate in medical sociology at UAB in 2014. “In my 20s I did primarily medical nutrition therapy and nutrition counseling, and I got pretty discouraged about the prospects of individual behavior change,” she said. “My medical sociology studies helped me appreciate the importance of social context. It is very difficult to make individual changes when there aren’t corresponding changes in the environment.” Health interventions are most impactful when they focus on more than one level of influence, Bateman explained. Her pilot study will work on the individual patient level, but it also touches the provider level by educating future physicians. “And, we hope to use the findings from this pilot intervention to apply for extramural funding to examine the efficacy of a multi-level intervention that would address individual-, physician- and health care system-level barriers to colorectal screening in Egypt,” she said. About her work as project manager for the existing National Academy of Sciences/USAID funded grant in Egypt, she said, “I saw how such work has the potential to have a significant impact in a low-to-middle-income country where resources may be scarce. I hope this project can make a difference as well.”

Farmers and fishing communities surrounding Sri Lanka's massive Lakvijaya coal power plant have long been concerned about its effects on marine life and their children's health.

Farmers and fishing communities surrounding Sri Lanka's massive Lakvijaya coal power plant have long been concerned about its effects on marine life and their children's health.

Sri Lanka: children, coal and development

PI: Meghan Tipre, DrPH

Other UAB participants: Nalini Sathiakumar, M.D., DrPH (senior mentor); Mark Leader

The question: What happens to children’s development when they breathe in the microscopic particles blowing from a nearby power plant?

Meghan Tipre was a student in the master's program in public health that UAB faculty developed with the University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka. Now, after receiving her doctorate in epidemiology at UAB, Tipre is leading a groundbreaking study of the effects of pollution on children's neural development.

Meghan Tipre was a student in the master's program in public health that UAB faculty developed with the University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka. Now, after receiving her doctorate in epidemiology at UAB, Tipre is leading a groundbreaking study of the effects of pollution on children's neural development.

Background: The Lakvijaya Coal Power Plant, which has been operating since 2011, is the first coal-fired power plant in Sri Lanka, an island nation of 21 million. Coal plants produce power by pulverizing and burning coal, leaving coal ash as the main waste product. Coal ash, in turn, is mostly made up of fly ash — particles that can be 100 times smaller than a human hair and can contain toxins including arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury. Children are particularly susceptible to inhaling or ingesting fly ash. Two previous studies, one in China and one in the United States, examined developmental effects in children living near coal plants. Both studies found adverse health effects — including higher rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), gastrointestinal problems, sleep disorders and developmental delays — among children living close to the plants. But a major drawback of these studies was that fingerprinting the fly ash from the power plants was not possible.

What has UAB already done? Researchers from UAB led by Sathiakumar and Sri Lanka’s University of Kelaniya are working together on an existing National Institutes of Environmental and Occupational Health grant to study the effects of indoor air pollution from cooking stoves on infant neural development. Sathiakumar, a professor in the Department of Epidemiology in the UAB School of Public Health, also spearheaded the establishment of the first master’s of public health program in Sri Lanka at Kelaniya supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health. Tipre is a graduate of that program whose doctoral dissertation, with Sathiakumar as her advisor, examined environmental factors predicting dengue fever in Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka.

Innovation: Tipre and a team of researchers from UAB and Kelaniya will use the Sparkman funding to conduct the first study in a low-middle income country on fly ash exposure and adverse health effects in children. This study also overcomes the limitation of previous studies in that fingerprinting fly ash from the power plant in question is possible. Samples of the fly ash waste from the Lakvijaya Coal Plant tested in a U.S. laboratory earlier this year by UAB researchers contained several trace metals, including arsenic, lead, chromium, mercury and cadmium, all of which have been linked with adverse health outcomes in humans.

“There are concerns about how the waste from the Lakvijaya plant is being handled,” Tipre said. “There are applicable regulations in Sri Lankan law, but there are concerns about whether they are being strictly enforced.”

The study setting is unique, Tipre said. Sri Lanka has a well-established primary care system with maternal-child health indicators on par with the United States and Europe, thus the usual confounding factors that affect child development raise little concern in the area. UAB researchers are engaging members of Sri Lanka’s Public Health Midwife corps, each of whom is assigned to monitor all children in her designated area — generally serving a population of 3,000 to 5,000. With help from the midwives, the researchers will recruit eligible participants in the study, collect health data from them and use mapping technology to compare health effects on 110 children ages 1-3 living within 5 kilometers of the plant, with health effects on a similar number of children living 10 to 15 kilometers away.

Impact: Preliminary data from this study could pave the way for larger studies and “possibly inform policy decisions,” Tipre said. “This is an excellent opportunity to do this work in a developing country.”

The opportunity for an early career investigator such as herself is exciting, too, Tipre added. “It’s not very often that researchers in the United States get pilot funding to do international work,” she said. “It’s a great initiative from a public health perspective, and I’m very grateful to the Sparkman Center.”

Sadeep Shrestha (seated by window) and colleagues in Nepal. Shrestha, a genetic epidemiologist, has already established a working group to study human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in the country. Now he is establishing a cancer registry and biospecimen repository to understand the factors behind Nepal's high rates of head and neck cancer.

Sadeep Shrestha (seated by window) and colleagues in Nepal. Shrestha, a genetic epidemiologist, has already established a working group to study human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in the country. Now he is establishing a cancer registry and biospecimen repository to understand the factors behind Nepal's high rates of head and neck cancer.

Nepal: Viruses, tobacco and head and neck cancer

PI: Sadeep Shrestha, Ph.D.

Other UAB participants: oncologist Ravi Paluri, M.D.; Amrita Mukherjee, doctoral student in epidemiology; Sanjeev Acharya, doctoral student in sociology.

The question: What factors lie behind the high prevalence of head and neck cancer in Nepal?

Background: Rates of head and neck cancer are very high in Nepal, a landlocked country that is among the poorest and least developed in the world. (About one quarter of its 29 million people live below the poverty line.) The actual prevalence is unknown, as there is no official national data due to a lack of cancer registries and hospitals equipped to gather the data. Worldwide, head and neck cancer collectively is the fifth most common malignancy, with more than 550,000 diagnoses and 380,000 deaths per year.

Smoking is implicated in a large proportion of head and neck cancer cases worldwide. Many Nepalis, both men and women, smoke or chew local tobacco products such as choor and kankat. And these products may confer a higher risk of head and neck cancer than typical tobacco cigarettes found in other countries. At the same time, infection with human papillomaviruses (HPV) also is a major factor. “People don’t realize that half of it can be caused by HPV,” said Shrestha, an associate professor in UAB’s Department of Epidemiology, where he holds the Quetelet Endowed Professorship in Public Health.

What has UAB already done? Shrestha, a genetic epidemiologist, studies the immunogenetics of HPV persistence and clearance, biomarkers of HPV-related pre-cancer and cancer progression, and the epidemiology of HPV-related cancers using hospital-based electronic medical records. A native of Nepal who came to the United States as a college student, he still regularly returns to visit family. During these trips, Shrestha has built partnerships with a local NGO, the Nepal Fertility Care Center (NFCC), the Nepal Cancer Hospital and Research Center (NCHRC), Kathmandu University and the government to boost diagnosis and research capabilities in the country. In partnership with Pema Lhaki, the director of the NFCC, Shrestha has established an HPV research working group in the capital city, Kathmandu, and has started building a network throughout the country. He also has established an HPV genotyping lab and a mobile testing station to reach people in the remote areas. “Before, we had to bring samples to the United States and test them here,” Shrestha said. “But it’s a long process, and while we did that we would lose patients for follow-up and treatment. What good is screening if you’re not there when the results come back? Now, with the mobile HPV testing, we can do testing in bulk in two to three hours, while people wait.”

Innovation: “We want to identify risk factors associated with head and neck cancer in Nepal,” Shrestha explained. “We’re going to establish a cancer registry with all important data, piloting with recruitment of 100 head and neck cancer patients at NCHRC where we will gather and establish electronic medical records on their demographics, residential information and risk behavior patterns — both tobacco/cigarette use and sexual behavior.” All these factors can inform head and neck cancer risk, Shrestha said. HPV testing will establish the prevalence of HPV types in the samples. The banked samples stored in the newly established biorepository also will help point researchers to biomarkers of head and neck cancer. “HPV has a vaccine but there isn’t really a treatment,” Shrestha said. “But pre-cancer lesions can be successfully treated, specifically in cervical cancer. It’s usually late-stage cancer by the time someone comes to the hospital in Nepal. If we can find biomarkers it will help us target the population that we really need to pay attention to. The goal is to screen and treat them before they develop cancer.”

Impact: The cancer registry and the biospecimen repository will “lay the foundation you need before you can ask research questions,” Shrestha said. They will help quantify risks associated with various local tobacco products, environmental exposures, local diets and specifically HPV, a sexually transmitted infection that most don’t want to discuss. “With the successes of immunotherapy, it would be important to differentiate HPV and non-HPV associated cancer for therapy,” Shrestha noted in his Sparkman Center grant application. The work will strengthen existing research collaborations with non-governmental organizations, hospitals and academic institutions in Nepal and help establish new collaborations with the government and the World Health Organization.

Neurosurgeons Brandon Rocque (right) and Jacob Lepard (center), along with Penn State's Steve Schiff, observe a procedure led by their Vietnamese counterparts at Children's Hospital 2 in Ho Chi Minh City.

Neurosurgeons Brandon Rocque (right) and Jacob Lepard (center), along with Penn State's Steve Schiff, observe a procedure led by their Vietnamese counterparts at Children's Hospital 2 in Ho Chi Minh City.

Vietnam: Hydrocephalus, spina bifida and rainfall

PI: Brandon Rocque, M.D.

Co-investigators at UAB: neurosurgeon James Johnston, M.D.; Jacob Lepard, M.D., sixth-year neurosurgery resident

The question: What are the factors behind cases of pediatric hydrocephalus and spina bifida in Vietnam — and do lessons from the relatively well-studied region of sub-Saharan Africa apply to Southeast Asia?

Background: Throughout the world, hydrocephalus and spina bifida are two of the leading sources of untreated neurosurgical disease in children. That includes the United States, where hydrocephalus — the buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain’s ventricular system, causing damaging pressure — “is far and away the most common reason for pediatric neurosurgery,” said Rocque, an associate professor in the pediatric division of the UAB Department of Neurosurgery. Another leading problem for pediatric neurosurgeons worldwide is spina bifida, a neural tube defect in which the backbone and spinal canal do not close before birth.

Prevalence and causes vary with geography, however. “For us, the No. 1 reason for pediatric hydrocephalus is there are lots of premature births in Alabama,” Rocque said. Whereas “it has been known for the past 15 years that post-infectious hydrocephalus is the predominant type in sub-Saharan Africa.” Myelomeningocele, a form of spina bifida, “is relatively rare in the United States, on the other hand, but it is a leading cause” of pediatric neurosurgery in Uganda, Rocque said. “We really don’t know what the No. 1 cause is in Vietnam. That’s what we aim to find out.”

Rocque, Lepard and Schiff are establishing a research partnership that will use data mapping to explore causes of hydrocephalus and spina bifida among Vietnamese children. Left to right: Le Nam Thang, chief of neurosurgery at National Hospital of Pediatrics in Hanoi; Brandon Rocque; Steve Schiff; Thanh Can Dang Do, chief of neurosurgery at Children's Hospital 2; Thanh Van Tran, CURE Neuro Southeast Asia regional coordinator; and Faizal Haji, former UAB pediatric neurosurgery fellow.

Rocque, Lepard and Schiff are establishing a research partnership that will use data mapping to explore causes of hydrocephalus and spina bifida among Vietnamese children. Left to right: Le Nam Thang, chief of neurosurgery at National Hospital of Pediatrics in Hanoi; Brandon Rocque; Steve Schiff; Thanh Can Dang Do, chief of neurosurgery at Children's Hospital 2; Thanh Van Tran, CURE Neuro Southeast Asia regional coordinator; and Faizal Haji, former UAB pediatric neurosurgery fellow.

What has UAB already done? “We’re building on a relationship that the department has developed during the past seven years,” Rocque said. Since 2013, the UAB Department of Neurosurgery and Children’s of Alabama have sponsored biannual trips to partner locations in Vietnam — including Children’s Hospital 2 in Ho Chi Minh City and the National Hospital of Pediatrics in Hanoi — for surgical education and research. The trips “have resulted in adoption of several new pediatric neurosurgical techniques in Vietnam,” Rocque noted in his Sparkman Center grant application. They also produced an “exchange of surgeons in both directions, including several Vietnamese senior and junior faculty spending two months with our Department of Neurosurgery,” said Rocque.

“It’s really a partnership,” Rocque said. “These are excellent surgeons; we learn a lot from them and they from us.”

These exchanges also have led to new research ideas. Both groups had spent time in Uganda, where the nonprofit CURE International has established a surgical center and research program exploring the causes of hydrocephalus and myelomeningocele. The CURE team encourages visiting surgeons to collect data on patients to help advance research. “They have all this data, so what can we do together?” Rocque recalled thinking. “We want to further the relationship and develop our Vietnamese colleagues in their research capabilities. Not show up, leave and publish but show them the process and get them on the research stage.”

Innovation: Lepard, a sixth-year resident in neurosurgery, spent the past year living in both Uganda and Vietnam as part of the research component of his residency. While Rocque provides oversight of the data collection and on-site data quality-assessment efforts, Lepard will build on research by project co-investigator Steve Schiff, M.D., of Pennsylvania State University. Schiff has used genetic exploration and satellite imaging to identify bacterial infection as the likely cause of much of the post-infectious hydrocephalus seen in Uganda. “Sixty-five percent of pediatric hydrocephalus in Uganda is caused by post-infectious hydrocephalus, whereas it’s less than 5 percent in the United States,” Rocque said. “The question for Vietnam: is it closer to Uganda or the U.S.? Is it common or uncommon? That’s a very simple question that we don’t know the answer to.”

Lepard is using cluster analysis and satellite imaging to map the hometowns of patients seen with pediatric hydrocephalus and myelomeningocele in the two pediatric hospitals. He will combine that information with data on rainfall collected by the Vietnamese national weather service. The goal is to see if the patterns match those reported by Schiff in Uganda, where periods of intermediate rainfall correlated with peaks of birth and infant fevers. Weather patterns have previously been associated with several infectious disease vectors, including mosquito populations and bacterial prevalence.

“UAB is in a unique position to assist the major pediatric neurosurgical centers in Vietnam to provide the answers to these questions,” Rocque and colleagues wrote in their Sparkman Center grant application.

Impact: “We have a pretty good idea of how to treat these conditions,” Rocque said. “The real goal is to prevent them. By the time a neurosurgeon sees these kids they’ve had a lot of damage.”

Hydrocephalus and spina bifida “tend to be diseases of poverty,” Rocque added. A novel connection between socioeconomic status and prevention of infant hydrocephalus and neural tube defects “could lend credence to advocacy efforts aimed at economic improvements in the region,” he wrote in the grant application. The project’s maps could help “guide strategic economic interventions in a region-specific manner to reduce poverty in areas where it would have the greatest impact on disease burden.”

All fifth-year neurosurgery residents complete a year-long research experience, Rocque noted. But Lepard is the first to do his out of the country. “I’ve always had an interest in international medicine,” Lepard said. “That was my goal for going into medicine in the first place, and from there I fell in love with neurosurgery. This is an exciting opportunity.”