Michelle Wooten, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics Michelle Wooten, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences, needed an activity that could both create community in astronomy courses AST 101, 102 and 103 and also give students a unique connection to class material. Finding that sweet spot is not an uncomplicated process, she explains, because astronomy instruction often remains confined to the conceptual.

Michelle Wooten, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics Michelle Wooten, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences, needed an activity that could both create community in astronomy courses AST 101, 102 and 103 and also give students a unique connection to class material. Finding that sweet spot is not an uncomplicated process, she explains, because astronomy instruction often remains confined to the conceptual.

Her solution? Incorporating artistic assignments into her scientific curriculum — a practice becoming more commonplace within science education, and one with which Wooten has firsthand experience.

“In grad school, I had an art pedagogy professor who had us doing art regularly in class,” she said. “Initially, we ‘smart grad students’ chuckled at how much our in-class art felt playful and childlike. And yet I will say that the assignments I did in that class still provoke my thinking to this day.”

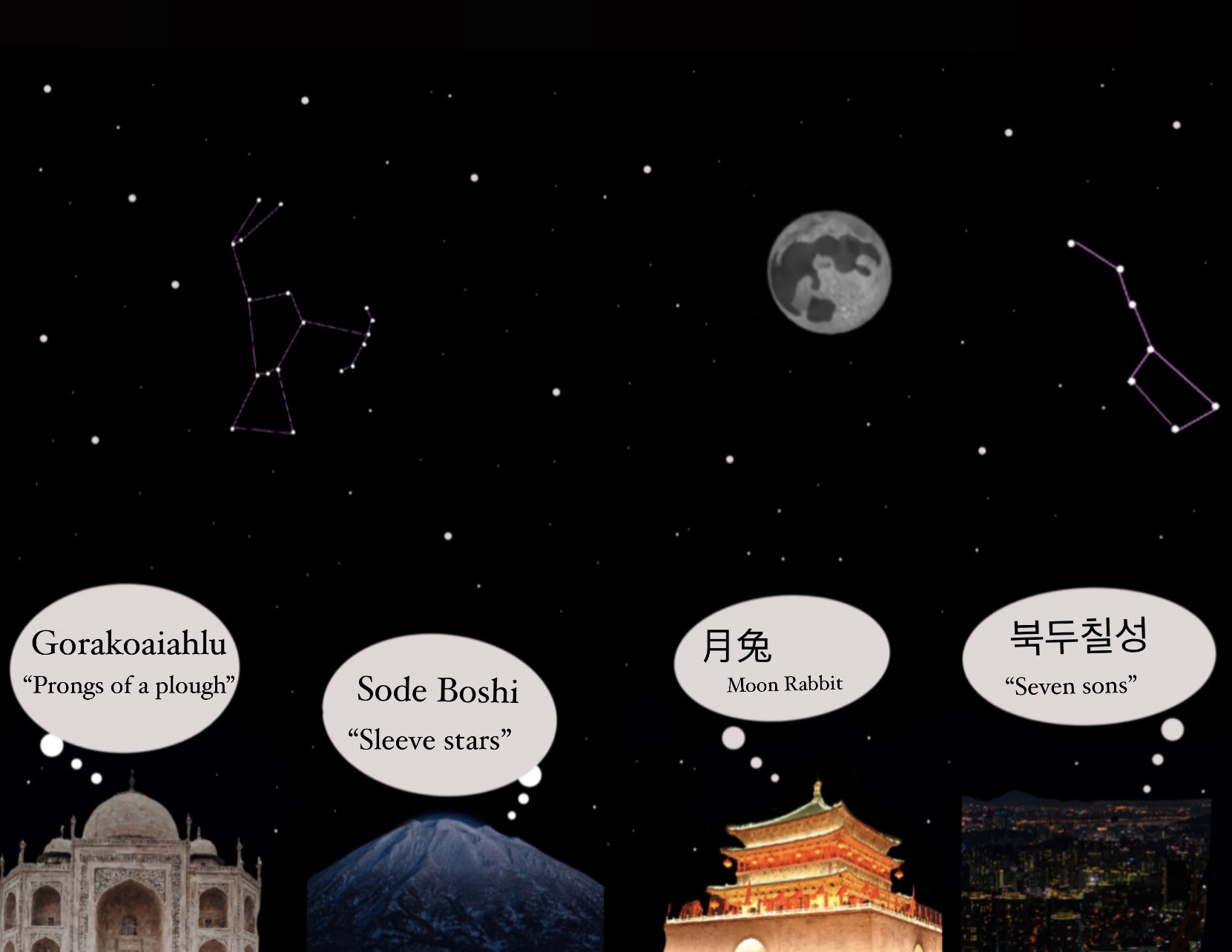

Wooten also drew from evolving trends in the astronomy education community when adding creative work into her curriculum. Educators known as “dark sky advocates” — members of a global community dedicated to protecting the night from light pollution — often incorporate art into their advocacy work to enable people to better realize and express their appreciation of the night sky, she explains. To support her ability to construct astronomy art assignments, Wooten attended planetary scientist and sci-artist Jamie Molaro’s Making Space workshop earlier this year. Wooten began using “Star Scenes,” an assignment written by Molaro, in her labs this summer. “Star Scenes” involves making a representation of a constellation in which specific star properties are embedded in shape, size and color, she explains.

Outside the lines

|

“Thinking artistically in a science class shifted my perspective from simply accepting all the information I was learning to making a personal connection with the material.” |

Because many of the students in AST 101, 102 and 103 are non-science majors, they often express what Wooten defines as “uneasy relationships with math and science.” By incorporating art assignments near the beginning in her courses, Wooten aims to provide a kind of steppingstone as the learning process begins.

“This early incorporation of art is purposeful,” she said. “I hope that, in giving students the opportunity to do art early on, those who are artfully inclined can express their strengths, and build personally meaningful connections to the course purview.”

Outside of a required assemblage project in AST 103, in which students use found objects to create artwork that explains a course concept, her students had flexibility to choose art mediums that they were most interested in or comfortable with — and their creative approaches never ceased to surprise, Wooten says.

By marrying the scientific with the artistic, Wooten hopes to enable students to step outside what she refers to as the more “reductive” nature of science — the acts of problem-solving and obtaining a study finding, which are central to the scientific process and remain a centerpiece in her courses — and shift their focus to science’s more “irreducible” side.

“In the process of making art, we make connections to our object of inquiry in ways that perhaps we had not considered before,” she explained, referencing theories from transdisciplinary philosophers that explore how working in unfamiliar territory can act as a learning tool. “I am interested in how practicing in-between disciplines can destabilize our comfort zones and consequently push us into flexible, de-hierarchized modes of thinking and relating.”

Story continues below photos.

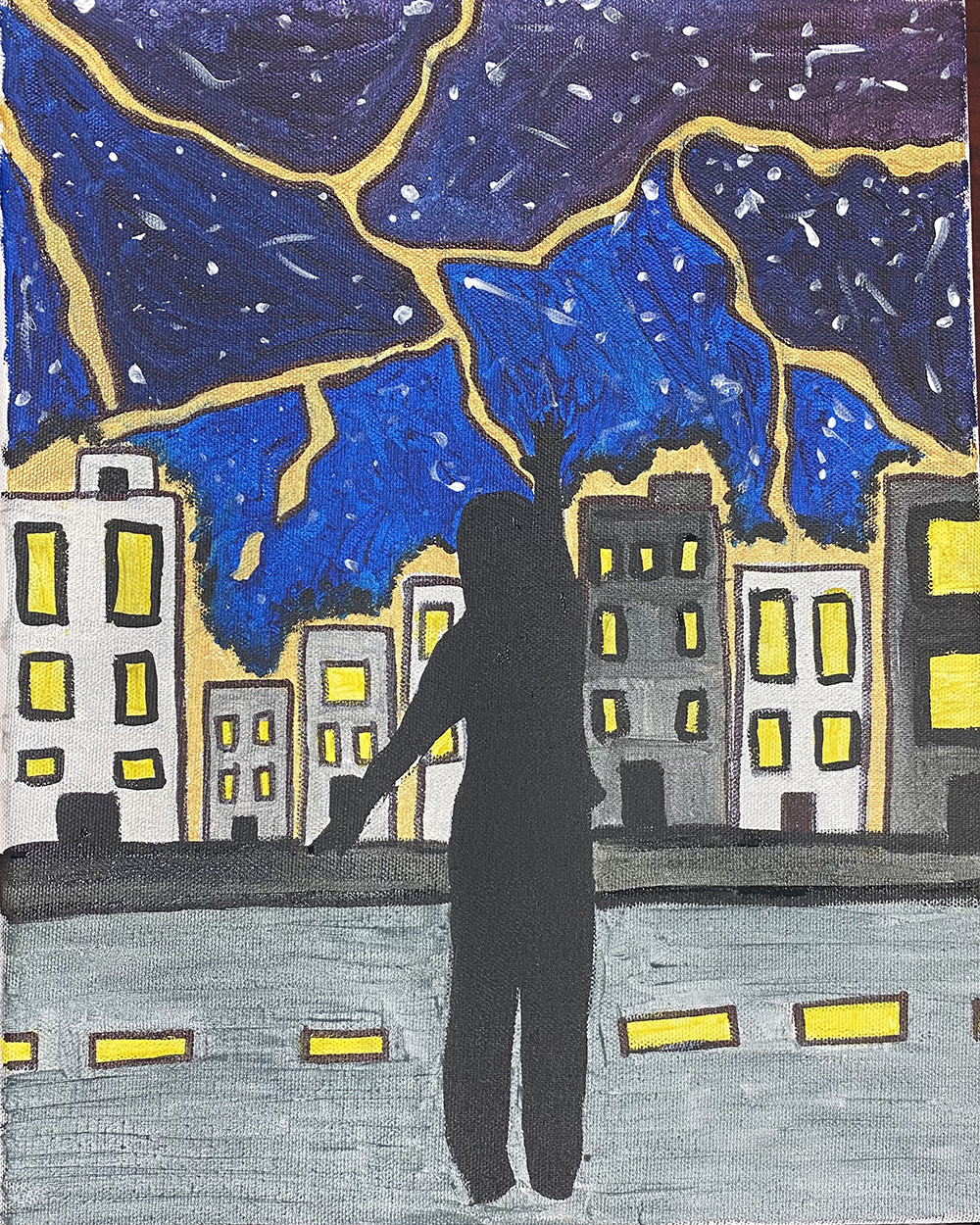

Left to right: Artwork created by students Helen Robinson and Holly Higginbotham

Angeles Del Carmen Cisneros, a sophomore majoring in criminal justice who took AST 102 in fall 2022, said the artwork assignment was “something different” from traditional coursework in science classes.

“The process of creating this assignment made us pause and pay attention to what our view of the night sky really seemed,” Cisneros explained.

|

“In the process of making art, we make connections to our object of inquiry in ways that perhaps we had not considered before. I am interested in how practicing in-between disciplines can destabilize our comfort zones and consequently push us into flexible, de-hierarchized modes of thinking and relating.” |

Helen Robinson, a sophomore who took AST 102 in person in fall 2022, says she was surprised that one of her first assignments would be to create an artistic representation of her relationship with the night sky, because she had expected to complete only science-based coursework in the class.

“Thinking artistically in a science class shifted my perspective from simply accepting all the information I was learning to making a personal connection with the material,” she explained. “Having this connection was a great way to start off the semester because it prepared me to think about how I’m linked to the topic. Art and science should work together, not be seen as opposites.”

A fresh perspective

At first glance, using the creation of artwork to better understand scientific concepts could be misinterpreted as unsophisticated, or even juvenile, but that perception oversimplifies its educational value, Wooten says.

Perhaps most importantly, utilizing student creativity can be a good way to make the field more accessible, she explains. Citing data from the American Institute of Physics, Wooten notes that women earn 53% of awarded STEM degrees in fields such as biology, but just 21% and 33% of physics and astronomy degrees — and that number shrinks to just 4% and 3% for Black women, respectively.

“Astronomy is a social undertaking that has both made incredible discoveries and done harm by privileging only some perspectives over time,” she said. “If we are not graduating persons from minoritized populations, we lose the benefit of their contribution and maintain our status quo of who gets to belong and do physics and astronomy.

“Currently, many people in our physics and astronomy disciplines are asking, ‘What are the conditions of our discipline such that minoritized populations choose other degrees? What can we do to make our disciplines more inclusive?’” she continued.

“By involving opportunities to make art, I hope to support students in making connections between astronomy and their personal lives, to learn course concepts with their multiple strengths, and to explore perspectives of people and cultures who have been excluded from the normative narrative.”

Story continues below photos.

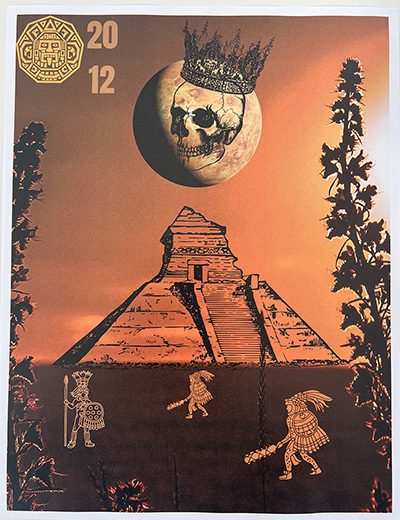

Left to right: Artwork created by students Dawn Davis, Bri Ross and Angeles Del Carmen Cisneros.

Connecting threads

Fostering personal connections can be especially important in Wooten’s online AST 101 and 103 courses, in which she’s found that “students sometimes express desire for more connection in the course” beyond the traditional interactive discussion boards. During the fall 2022 semester, Wooten experimented with a class movie night for AST 101, 102 and 103, during which they watched the 2016 Academy Award-winning film “Arrival,” which explores the possibilities of communication with extraterrestrial intelligence.

Wooten also organized an art showcase in UAB’s ArtPlay for AST 101, 102 and 103 students, during which students could observe their classmates’ artwork and discuss their individual pieces; other Blazers who saw the event advertised on the Campus Calendar stopped by to take in the artwork, including CAS Dean Kecia Thomas and Catherine Daniélou, senior associate dean for Undergraduate Academic Affairs.

Artwork created by student Ashton Reno“I was delighted by how much learning and community-building came from that experience,” she said. “I am really grateful to my department and to UAB for their support in these endeavors.”

Artwork created by student Ashton Reno“I was delighted by how much learning and community-building came from that experience,” she said. “I am really grateful to my department and to UAB for their support in these endeavors.”

These kinds of creative approaches for online courses are part of what makes UAB unique; UAB Online recently was ranked by Newsweek as No. 15 on its list of America’s Top Online Colleges for 2023. This recognition puts UAB’s online courses among the top 7.5% of the best and most sought-after in the country, and UAB as the highest-ranked Alabama university on the list.

Sarai Gwin, an online student in AST 101, says the unique assignments in her course enabled her to harness the creative skills she has cultivated since childhood and apply them in a unique way — something she has not often encountered in her STEM studies. During one assignment, Gwin chose to write a poem as a medium to explore the Mayan culture’s relationship to astronomy.

“Since a young age, I have always been a creative individual,” she explained. “I love art, music, dance, poetry — you name it. Being in STEM, it’s not every day that my passion for the arts and my passion for the sciences get to coexist in the same space, especially in the academic space.

“[Writing a poem] really helped me to visualize what that time could have been like in Mayan culture, as well as the Mayan history of astronomy. I was able to articulate the feelings and thoughts I had about the information I had read in a way that a short essay would not convey in the same way. I have always been fond of creative writing and songwriting, and to be able to merge that passion with science was one of my favorite assignments that I have completed in a while.”