Andy Baer, assistant professor of historyWhen Andy Baer, Ph.D., was living in Chicago and studying at Northwestern University, he took part in a die-in at city hall to protest a history of brutality by Chicago’s police force. The event was spurred by the 2010 civil trial of Jon Burge, the infamous police detective and commander who, together with fellow officers, tortured more than 200 criminal suspects, most of them black, to coerce their confessions between 1971 and 1991.

Andy Baer, assistant professor of historyWhen Andy Baer, Ph.D., was living in Chicago and studying at Northwestern University, he took part in a die-in at city hall to protest a history of brutality by Chicago’s police force. The event was spurred by the 2010 civil trial of Jon Burge, the infamous police detective and commander who, together with fellow officers, tortured more than 200 criminal suspects, most of them black, to coerce their confessions between 1971 and 1991.

To Baer’s left lay Bill Ayers, co-founder of the American militant, radical left-wing revolutionary group Weather Underground. To his right lay renowned law professor Bernardine Dohrn, also a member of Weather Underground.

Meeting Ayers and Dohrn at that demonstration reflected a larger trend Baer had noticed at protests and rallies: a significant presence of radical leftist demonstrators — both older, white radicals and younger, multiracial activists — focused on human-rights awareness.

“They saw the Burge scandal as just one piece of a larger system of capitalist oppression,” Baer said.

Baer, assistant professor of history, has studied race and policing in American cities for years, and he explores just how closely radicalism, race and police brutality are intertwined in his newest project, “Beyond the Usual Beating: The Jon Burge Police Torture Scandal and Social Movements for Police Accountability in Chicago, 1972-2015.”

Communists and radical leftists have consistently aligned themselves with convicted non-white criminals and against criminal justice institutions they believe perpetuate classism and racism, Baer says. From the 1930s to the ’90s — spurred by events such as the Great Depression, the Scottsboro Boys trials, the civil rights movement and the Burge police scandal — there is an unbroken connection between the radical left and African-American prisoners.

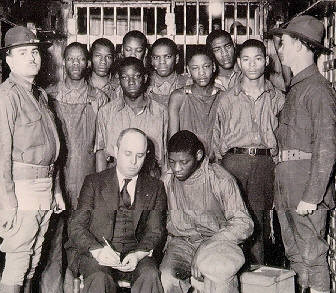

The Scottsboro Boys, seen here with attorney Samuel Leibowitz, were placed under guard by the state militia in 1932.Starting in Scottsboro

The Scottsboro Boys, seen here with attorney Samuel Leibowitz, were placed under guard by the state militia in 1932.Starting in Scottsboro

The 20th century tradition of the radical left advocating for blacks alleged to have committed crimes most notably can be traced to the case of the Scottsboro Boys, Baer said. In 1931, nine black teenage boys were arrested and charged with raping two white women. After multiple trials, the first of which took place in Scottsboro, Alabama, the case ultimately was sent to the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal. Seven of the accused served prison sentences, and all of those were released or escaped by 1946. In 1976, Alabama Gov. George Wallace pardoned Clarence Norris — the only one given a death sentence — who had jumped parole 30 years prior.

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA) had established a strong foothold in Birmingham by the time the Scottsboro Boys went on trial and became more widely known in the South through its defense of the teenagers.

CPUSA hired the International Labor Defense, a legal advocacy organization, and the American section of Communist International’s International Red Aid network, to defend the Scottsboro Boys. Communist black attorney William L. Patterson, who led the ILD and launched a broad political campaign to free the nine boys, was at odds with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which pursued a legal strategy.

“Radicals tend to filter through criminal cases to find the most interesting one,” Baer said. “It might not always be an overly sympathetic case.”

That was certainly true of the Scottsboro Boys case, he said; while some Northerners were sympathetic, most Southerners were virulently opposed to their acquittal. The ILD was responsible for reversing convictions during the defendants’ second retrial, but the third trial ended in convictions.

Connecting the dots

The Black Panther Party held a rally on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1970.Eugene V. Debs, five-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America, famously said in 1918, “While there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

The Black Panther Party held a rally on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1970.Eugene V. Debs, five-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America, famously said in 1918, “While there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

As socialist and other radical ideologies developed during the decades, spurred and shaped by contemporary events, they have remained tied to the ideals professed by Debs. Specifically, Baer said, communists and radical leftists have consistently aligned themselves with convicted non-white criminals and against criminal justice institutions they believe perpetuate classism and racism.

“The radical left begins at the premise that American institutions are illegitimate, especially in terms of criminal justice,” Baer said. “So they are often less skeptical of the claims of the inmate.”

Groups such as the Black Panther Party, a revolutionary black nationalist organization founded in the 1960s, adopted many facets of the radical left ideologies. The Black Panthers were an inherently socialist organization, Baer said, and had an “international view of class oppression.”

“They believed in the interracial solidarity of the working class — blacks, Latinos and poor whites,” said Baer, who will be teaching a HY 393-1D course this fall on black freedom movements in the United States.

“The radical left identifies with state prisoners as victims of the state,” Baer said. “They romanticize, venerate and celebrate the poorest, the least educated and the least skilled … and they are not worried about alienating the mainstream media or political parties.”

A new campaign

These beliefs were easily applied to the Burge scandal. It was simple, Baer said, for radical leftists to see parallels between the wrongful convictions of tortured black men during Burge’s reign and the Scottsboro Boys case.

|

“The radical left begins at the premise that American institutions are illegitimate, especially in terms of criminal justice... Radical leftists cannot trust the state and are not going to take the ‘official word,’ so they are often less skeptical of the claims of the inmate.” |

Ten of the men tortured by Burge were convicted and sentenced to death. On their behalf, the Campaign to End the Death Penalty (CEPD), an offshoot of International Socialist Organization (ISO), campaigned to raise awareness for the inmates and gain national attention for their platform — the abolition of the death penalty in America.

“The CEPD and the ISO were drawing straight lines from the Burge victims to the Scottsboro Boys,” Baer said. “From the 1930s to the ’90s, there is this unbroken connection between the radical left and African-American prisoners.”

This story is part of a series on UAB researchers studying communism and radical left-wing politics. In case you missed it, read about Birmingham’s complicated relationship with communism and the influence of pre-revolution Russia on modern African-American politics.