Written by Lesley McCollum

Deaths from opioid overdose are at an all-time high across the United States, and Birmingham has been hit particularly hard. In the past four years, heroin overdose deaths in Jefferson County and surrounding areas rose from 12 individuals to 137. But a team of UAB researchers is taking action to respond.

The group is led by Karen Cropsey, Psy.D., an associate professor in theUAB School of MedicineDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology. Cropsey specializes in substance abuse treatment in vulnerable populations; some of her current research programs involve treatment of individuals in the criminal justice system and people living with HIV/AIDS. She regularly witnesses the devastation of prescription opioid and heroin overdose in Birmingham. “I felt like there was something we could do about that,” she said.

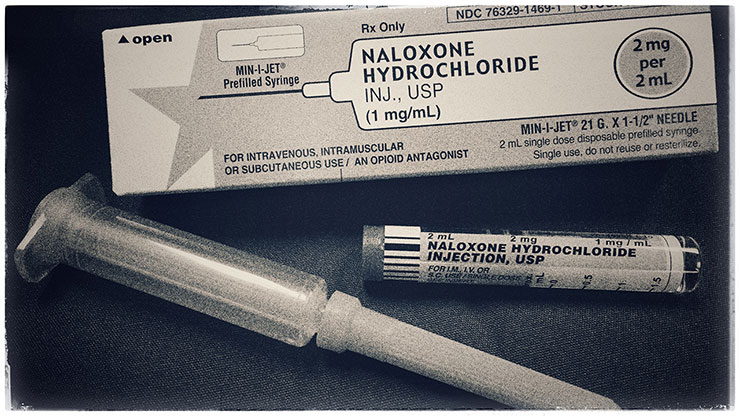

To combat the rising rates of death from overdose, Cropsey and her team are exploring the distribution of naloxone kits directly to individuals with opioid addictions, or their caregivers. Using naloxone isn't a new idea. It's been the standard of care for opioid overdose in emergency rooms, including at UAB, since the early 1970s. The kits offer a last resort option to reverse an opioid overdose and prevent death. Several states, including California, New Mexico and Massachusetts, have successful local distribution programs for naloxone. In 2010 the CDC reported that since the first local distribution programs began in 1996, naloxone kits have prevented more than 10,000 deaths from opioid overdose.

Naloxone to the people

Cropsey and her colleagues want to bring a naloxone program to Birmingham as well. But “our program is different,” Cropsey said. Instead of distributing naloxone kits to first responders and law enforcement officers — the typical model — the UAB team wants to try a new approach: prescribing kits to individuals.

By taking advantage of the new Crowdfunding at UAB site, Cropsey’s team raised grassroots financial support for a unique study. In 30 days, the team collected $11,500 in pledges — enough to purchase more than 200 naloxone kits. Now they’re working to get the kits into the hands of the people who need them most: active opioid and heroin users.

The researchers are now hanging flyers around Birmingham and screening individuals interested in participating. They will be collecting information on how many kits are used, how many deaths they prevented and if participants follow up with treatment options after using naloxone. “I want to demonstrate that these kits can save lives,” Cropsey said.

Participants in the study are receiving training “on how to recognize signs of opioid overdose and how to administer the naloxone,” Cropsey said. They are instructed to then call 911 and go to the emergency room. Training is also being offered to friends or family members. It’s analogous to an EpiPen for someone with allergies, or insulin for someone with diabetes, Cropsey says the person who is prescribed the treatment may not be able to use it when it’s needed.

How naloxone works

When a person overdoses on an opioid, their breathing starts to slow down. After about one to two hours — or as short as a few minutes — breathing slows to a stop. This leaves a narrow but vital window to intervene. Opioids such as heroin or prescription drugs, including hydrocodone and oxycodone, work by latching on to receptors in the brain that produce their powerful effects. Naloxone rapidly displaces these drugs and then occupies the receptors so the opioid cannot return. Within minutes, the opioid is completely removed and the person who overdosed begins to breathe again.

But that success comes at a price. With complete removal of the opioid’s effects on the brain, naloxone puts the user into immediate, severe withdrawal. Imagine a sudden onset of the worst flu-like symptoms you’ve ever had, Cropsey explained. It’s “the nuclear option for people who would otherwise die.”

| Make a gift to support the naloxone crowdsourcing project |

“They need to be alive to get treatment”

Working with such a stigmatized group of people brings challenges, Cropsey says. She often hears that people addicted to drugs should just quit — that they choose to be addicted in the first place and need to choose to stop. But while addiction does start as a choice, Cropsey explains, it doesn’t take long for a user’s system to get hijacked by the drugs.

Besides, many of us are dealing with the consequences of choices that negatively affect our health, she adds. Whether it’s Type 2 diabetes or obesity from our eating habits, or lung cancer from smoking, a majority of the leading causes of death result from behavioral choices we make, Cropsey said. “Addiction is a medical disease just as much as heart disease or diabetes.”

In an ideal world, no one would use drugs, Cropsey said. “Unfortunately that’s not the case here. We don’t live in an ideal world.” More than 2.5 million people in the United States abuse prescription opioids or heroin. Addiction finds its way into the lives of our families, friends and coworkers, Cropsey said. “What would you do if this was your friend or family member?”

Cropsey acknowledges the argument that distributing kits is simply enabling addiction. Naloxone kits reduce harm of overdose by preventing death, she says, but they aren’t the complete picture. “The goal is to get people substance abuse treatment to help them stop using opioids,” Cropsey said. “But they need to be alive to get treatment.”

If you are actively using a prescription opioid or heroin, or are the friend or family member of an active user, and are interested in learning more about the program, call 205-975-4528 and ask about the naloxone study.