In September, a small group of eminent leaders from business, academia, medicine, science and public policy gathered for the inaugural meeting of the UAB School of Medicine Board of Visitors. The Board will meet twice a year to advise Senior Vice President for Medicine and Dean Selwyn M. Vickers, M.D., FACS, in support of the school’s vision to become the preferred academic medical center of the 21st century. Co-chaired by Huntsville native Ted W. Love, M.D., and Gail H. Cassell, Ph.D., the Board will serve as advocates and advisers on strategy, philanthropic initiatives, and community engagement, and provide independent perspectives on School of Medicine initiatives.

In September, a small group of eminent leaders from business, academia, medicine, science and public policy gathered for the inaugural meeting of the UAB School of Medicine Board of Visitors. The Board will meet twice a year to advise Senior Vice President for Medicine and Dean Selwyn M. Vickers, M.D., FACS, in support of the school’s vision to become the preferred academic medical center of the 21st century. Co-chaired by Huntsville native Ted W. Love, M.D., and Gail H. Cassell, Ph.D., the Board will serve as advocates and advisers on strategy, philanthropic initiatives, and community engagement, and provide independent perspectives on School of Medicine initiatives.The September meeting agenda included presentations by UAB faculty on key research initiatives in diabetes, neurosciences, cardiovascular disease, and personalized medicine and genomics. The Board concluded their visit with a dinner at Woodward House.

“In the time since I returned to Alabama to serve as senior vice president and dean of the School of Medicine, I have gained a deeper appreciation for this institution, its people, and the promise it holds for transforming medicine and science across a wide range of disciplines,” Vickers says. “More than ever, I am convinced we have a compelling and inspiring story to tell, and that we need to do a better job of telling that story outside the Southeast. The Board will help us do that.”

“As an Alabama native I’m very proud of our world-class academic medical center, and I’m excited to help it develop to even greater heights under Dr. Vickers’ leadership,” says Love. “UAB School of Medicine has many strengths, but I’m particularly impressed with its scale and quality of leadership. I believe continuing to build upon our outstanding faculty and research funding is key to our future as a leading medical center.”

Cassell says the strength of Vickers’ vision for the school compelled her to accept the invitation to co-chair the board. “One of the things I am so encouraged by is his commitment to invest in research, both basic and clinical, as well as his commitment to global health,” she says. “I will work hard to try to help him accomplish his vision, and I think other members of the board will do the same. It’s a very strong group of people committed to trying to advance the institution.”

Former Faculty Chair Brings Global Perspective

Cassell is one of two distinguished School of Medicine alumni on the Board of Visitors. Currently senior lecturer in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a senior scientist in the Division of Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, she recently retired from Eli Lilly and Co. as vice president for scientific affairs and Distinguished Lilly Research Scholar in Infectious Diseases.

Cassell is one of two distinguished School of Medicine alumni on the Board of Visitors. Currently senior lecturer in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a senior scientist in the Division of Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, she recently retired from Eli Lilly and Co. as vice president for scientific affairs and Distinguished Lilly Research Scholar in Infectious Diseases.A native of Goodwater, Ala., Cassell earned her bachelor’s degree in microbiology at the University of Alabama. She earned her Ph.D. in microbiology from UAB and chaired the Department of Microbiology for 10 years, during which it ranked first in NIH research funding.

During her wide-ranging career, Cassell has served as an advisor to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy; as an invited participant in numerous congressional hearings related to infectious diseases, anti-microbial resistance, and biomedical research; and on advisory boards for the directors of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control, the Secretary of Health and Human Services Advisory Council of Public Health Preparedness, and the Food and Drug Administration’s Science Board. She is a member of the Institute of Medicine and recently completed a second three-year term on its governing board.

Cassell’s broad experience in academic administration and public policy have given her a powerful perspective from which to assess the landscape for academic medical centers like the School of Medicine. In responding to current regulatory and funding challenges, Cassell says AMCs must take care to avoid certain pitfalls. “The biggest mistake that institutions make in my opinion is that they place so much emphasis on retention of more senior faculty without at the same time renewing within a department and recruiting younger faculty,” Cassell says. “They can find themselves kind of empty handed at the assistant professor level, and it becomes more difficult to recruit if you don’t have the full spectrum of talent. Then you have more of a challenge recruiting grad students and post docs, so it can have a very big impact. When you get a decline in research funding and the competition increases, there’s a tendency to hunker down and avoid risks. I think you have to be mindful that these things can have very long-term consequences and are not easily corrected.”

Cassell is optimistic that new models of public/private partnership will develop to counteract the decline in federal research funding. “I see great opportunities to partner with the private sector in all types of medically related industries—the pharmaceutical industry, the medical device industry. I think new models will arise for ways of collaborating that we’ve not seen in the past.” In Cassell’s view, globalization is a prime catalyst for these new types of partnerships. “There are major opportunities on the international front,” she says. “It’s now mandatory in science to have global collaborations, and that brings with it not only the opportunity to expand your research expertise but also to gain access to more and different funders of biomedical research.”

Cassell says genomic science holds untold possibilities for institutions like the School of Medicine. “It probably goes without saying that one big area of future opportunity is in the area of genomics in diagnostics, patient management, and treatment,” she says. “It seems to me that the recent partnership between UAB and the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology is a tremendous opportunity going forward to take advantage of each other’s strengths and become very competitive internationally in the area of genomic research.”

Talking the Talk

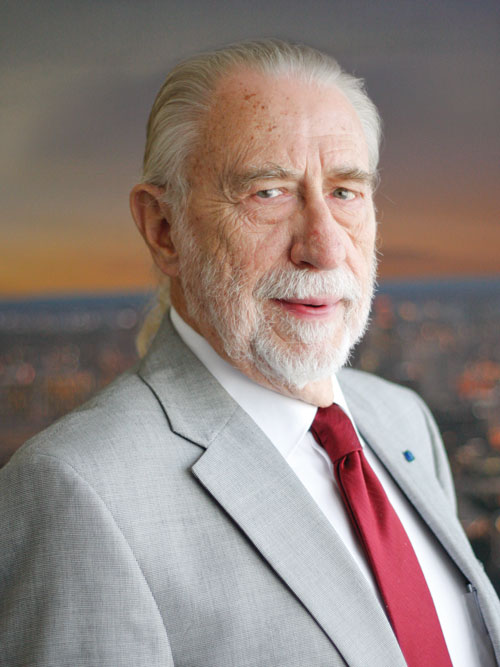

Dubbed “Online Health Care’s Medicine Man,” George D. Lundberg, M.D., has been at the forefront of most major developments in medical communication in the modern era. He has more than 30 years combined experience as editor in chief of The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the 10 AMA specialty journals, American Medical News, Medscape, The Medscape Journal, e-Medicine from Web MD, and MedPage Today from Everyday Health. He is currently editor in chief, chair of the editorial advisory board, and chief medical officer for CollabRx. He is also president and chair of the board of directors of The Lundberg Institute, a consulting professor at Stanford University, and editor at large for Medscape from WebMD, and is a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. Born in Florida, Lundberg grew up in rural Silverhill, Ala. He completed his undergraduate degree at North Park College and the University of Alabama before attending medical school at the University of Alabama School of Medicine. He completed a clinical internship in Hawaii and a pathology residency in San Antonio, then served in the U.S. army for 11 years. Lundberg served as professor of pathology and associate director of laboratories at the Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center for 10 years, and for five years was professor and chair of pathology at the University of California-Davis.

Born in Florida, Lundberg grew up in rural Silverhill, Ala. He completed his undergraduate degree at North Park College and the University of Alabama before attending medical school at the University of Alabama School of Medicine. He completed a clinical internship in Hawaii and a pathology residency in San Antonio, then served in the U.S. army for 11 years. Lundberg served as professor of pathology and associate director of laboratories at the Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center for 10 years, and for five years was professor and chair of pathology at the University of California-Davis. Not surprisingly given his background, Lundberg maintains that effective communication is an essential part of health care. “The practice of medicine includes surgeons who cut on people, radiologists who shoot ray guns at people, and internists and pediatricians who give chemicals to people, and the rest is communication,” he says. “Handling information—gathering it, evaluating it, discarding it, acting on it, dispensing it—that’s basically the whole practice of medicine.”

The importance of communication was instilled in Lundberg as a child. “My mother wrote for newspapers across Baldwin County,” he says. “I watched her hand write a weekly column for the Foley, Fairhope, and Bay Minette newspapers about what happened in Silverhill that week. Many people in our little town would bring their information to my mother to make sure they made it into the next edition of the Foley Onlooker or the Fairhope Courier. That is among my earliest memories and it certainly had something to do with conditioning me to the importance of communication.”

While the digital revolution has enabled information to flow at a previously unimaginable pace, Lundberg laments that the application of new research discoveries into clinical care remains agonizingly slow. “Doctors tend to continue to practice what they learned as residents until something jars them into doing something differently,” he says. “There is value to being resistant to change because sometimes the change may not be valid, so you need to keep your eye on it. But even so, the lead time from putting a real discovery that matters and can improve patients’ lives into routine practice can be as much as 15 years.”

Addressing that delay is at the center of Lundberg’s newest enterprise, CollabRx, a data analytics company that uses cloud-based expert systems to inform health care decision-making. “CollabRx deals exclusively in cancer and is dedicated to moving the best cancer treatment information on the worst cancers, the big killers, from discovery to use as rapidly as possible,” Lundberg says. “We’re trying to cut that 15 years down to a much shorter time.”

In Lundberg’s view, the School of Medicine is well-positioned to take a leadership role in addressing a number of challenges currently facing the American health care system. “I think that practical realities should cause UAB to try to convert problems into opportunities whenever possible, including the population health problems in that part of the country” Lundberg says. “I would recommend looking at the key problems that are killing and disabling the people who live in that area—I would think that obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and cancer are the biggest. UAB should really take advantage of these massive public health problems to try to do population-based research that can be turned into population-based interventions as well as personalized solutions for individuals.”

Health disparities is another area in which Lundberg sees unique opportunities for the School of Medicine. “Those are really big challenges but that’s where the payoff will be—in tackling huge issues and at least trying to stop them from getting worse, and then working to try and make them better.”