Twenty-one living donors have changed the lives of 21 recipients so far as part of the nation’s longest ongoing single-center paired kidney transplant chain, which is under way at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. The UAB kidney chain is scheduled to resume with six more transplants the week of July 7.

Twenty-one living donors have changed the lives of 21 recipients so far as part of the nation’s longest ongoing single-center paired kidney transplant chain, which is under way at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. The UAB kidney chain is scheduled to resume with six more transplants the week of July 7.The chain began Dec. 5, 2013, with Pelham, Ala., resident and donor Paula Kok, and is currently paused after Brookwood, Ala., resident Thomas Freeman was transplanted May 23. Kok approached UAB about the possibility of donating a kidney to a stranger in need this past fall and was committed to donating a kidney despite not having an intended recipient. In a paired transplant chain, a donation like this can set off a series in which family or friends of recipients give a kidney to another person in need – essentially paying donations forward on behalf of a loved one.

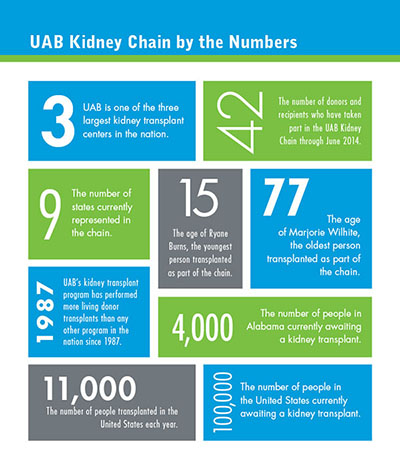

Kok’s altruistic gift began a chain of transplants that involves people from nine states — Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana, Texas, Illinois and New Jersey.

The chain was featured nationally on the ABC News program “Nightline" on July 3, 2014 and across multiple news outlets. The program featured several members of the current chain and showcased the work of UAB Medicine physicians, nurses and staff who helped make this lifesaving, complex chain a reality.

“To me, these are miracles,” said Jayme Locke, M.D., surgical director of the Incompatible Kidney Transplant Program in UAB’s School of Medicine and coordinator of the chain. “This is a game changer, a life changer for 21 patients and their families and friends. And none of it would have been possible without the selflessness of 21 donors and the hard work of our transplant team of surgeons, transplant nephrologists, lab technicians, transplant operating room team, nurses and staff.”

Development of the incompatible kidney transplant program at UAB has been a remarkable team effort.

“From our perspective, this is a significant achievement for the 100,000 people around the country on the waiting list for a transplant, including almost 4,000 people here in Alabama,” Locke said.

The chain even endured the January snowstorm that crippled the Southeast the week of Jan. 27; patients trekked to UAB from as far away as Florida and Mississippi that week, and surgeons, nephrologists, nurses and support staff spent three days and nights in the hospital to ensure the success of the chain and give the gift of life.

“This kidney chain really highlights an institutional commitment and the ingenious work of our transplant team to provide opportunities for lifesaving treatments for multiple people beyond our standard clinical techniques,” said Selwyn Vickers, M.D., senior vice president for Medicine and dean of UAB’s School of Medicine. “The hard work of Jayme Locke and her colleagues has already affected so many lives here in Alabama and across the country, and it will continue to do so. This is another example of how UAB wants the best care in the world to occur here in our state for our citizens and, at the same time, have a resounding impact on health care across the country.”

UAB’s program that can make transplantation possible between some donors and recipients who would otherwise be incompatible is the South’s leading incompatible kidney transplant program and the only one of its kind in the Southeast. It also fills a major need in Alabama, with more than 3,700 candidates on the kidney transplant waiting list, the second largest in the country.

Many programs offer living donor kidney transplantation but require a completely compatible match. UAB’s program offers patients pretreatment to overcome blood group and/or HLA incompatible barriers. Paired donation options further reduce incompatibility and facilitate less challenging transplants.

“We have the ability to use our paired-exchange and incompatible transplant programs in tandem to identify and connect potential living donors with recipients who have no other options, multiplying the number of successful transplants that can be performed,” Locke said.

Forty-one of the 42 surgeries were performed at UAB Hospital. One recipient, 15-year-old Ryane Burns of Union, Miss., was transplanted at Children’s of Alabama, signifying it as the only program in the Southeast to offer living kidney paired donation to those younger than 18. Patients who receive living kidney donations will have their new kidney work for an average of almost 15 years, with some lasting up to and beyond 30 years, Locke says.

Forty-one of the 42 surgeries were performed at UAB Hospital. One recipient, 15-year-old Ryane Burns of Union, Miss., was transplanted at Children’s of Alabama, signifying it as the only program in the Southeast to offer living kidney paired donation to those younger than 18. Patients who receive living kidney donations will have their new kidney work for an average of almost 15 years, with some lasting up to and beyond 30 years, Locke says.“UAB has become a national leader in kidney transplantation since performing our program’s first kidney transplant in 1968,” said Devin Eckhoff, M.D., director of UAB’s Division of Transplantation. “Our kidney program has done more living donor transplants than any other program in the United States since 1987, and it is one of the three largest kidney transplant centers in the nation. Our experience in performing kidney transplants from living donors ensures the highest level of care and better outcomes for our patients — both kidney donors and recipients.”

UAB is also leading national research efforts into incompatible transplantation and other areas of kidney disease. Vineeta Kumar, M.D., medical director of the Incompatible Kidney Transplant Program, and Locke are principal investigators in several clinical trials looking at ways to optimize therapies. Roslyn Mannon, M.D., director of research at the UAB Comprehensive Transplant Instituteand also a kidney transplant specialist, is among those leading investigative efforts to help patients keep transplanted organs permanently.

“Several therapies now used around the world to prevent transplant rejection were first offered to patients at UAB,” said Robert Gaston, M.D., executive co-director of UAB’s CTI. “The goal of our current research efforts is not just success in preventing rejection, but identifying treatments that allow transplanted kidneys to last the full lifetime of the recipient.”

More national coordination needed

More than 100,000 people in the United States are awaiting a kidney transplant, but there are only enough donor kidneys for 11,000 transplants each year. More than 15 percent of people on the waiting list will die before they receive a transplant.

More living donors, like Kok, are needed to put a dent in those daunting numbers, says Locke; but she also says more can be done at the national level to ensure more transplants take place.

“If our goal is the patient and the 100,000 people who are waiting on a transplant, it just makes intuitive sense that we come together and form one national program in which all kidney transplant centers participate,” Locke said. “Chains like this one have the potential to be an incredible game changer, but it’s going to require us to come together as a country and create one national system that requires all centers to participate so these patients realize the full benefit of what’s available to them.”

Locke says this program should extend so that each center includes all of its paired kidney donors into this database, including patients who are compatible and incompatible.

“There is a huge strength in numbers, and the more we can encourage donors and recipients to participate in paired kidney donation — even as a compatible pair, which we were able to accomplish in our UAB kidney chain — you can gain things by participating in these exchanges,” Locke said. “We can find a younger kidney for a recipient, or even find another perfect match, and all of those things can benefit our patient population.

“If we could do this, we could optimize living kidney donation in this country in a way that we have never been able to do before, and I think we can actually begin to make a significant dent in our waiting list.”

The infrastructure for UAB’s program has been put in place over a decade, and it has remained as a single center due in large part to necessity. Many of the transplants UAB surgeons perform, including several in this chain, would not have occurred through a national paired-exchange program, which traditionally requires completely compatible matches. Though other centers around the country have similar capabilities, UAB’s program of combining desensitization with paired donation is unique in the Southeast.

Read more about the UAB kidney chain, including stories from many of those involved, at www.uab.edu/kidneychain, and join the conversation online at www.facebook.com/uabkidneychain and on Twitter at #uabkidneychain.

To become a living kidney donor, visit uabmedicine.org/kidneytransplant, or to indicate your interest in donating your organs after death, visitwww.organdonor.gov and sign up today.