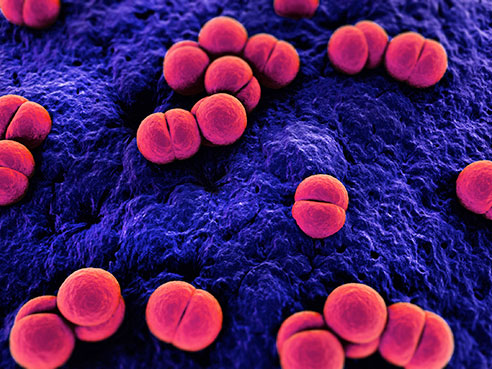

Cryptococcosis is a fungal infection caused by numerous species, two of which cause the majority of cryptococcal infections in humans and animals: Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Both species can be found in soil throughout the world and cause infection once they are inhaled, particularly in people with weakened immune systems.

Cryptococcosis is a fungal infection caused by numerous species, two of which cause the majority of cryptococcal infections in humans and animals: Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Both species can be found in soil throughout the world and cause infection once they are inhaled, particularly in people with weakened immune systems.C. neoformans infections cause an estimated 1 million cases of cryptococcal meningitis per year among people with HIV/AIDS, resulting in approximately 625,000 deaths worldwide. C. gattii infections are more common in tropical and subtropical regions. In recent years, cases have emerged in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia, and are currently under public health surveillance.

“Most people are infected with Cryptococcus when they’re children; you inhale it and it becomes a controlled dormant infection, and then it can reactivate in adulthood,” said Peter Pappas, M.D., professor of medicine. “It’s not contagious in the normal sense of the word; it is not something you are going to pick up from somebody else unless you are given a contaminated organ during a transplant.”

Pappas is currently exploring why this infection develops in patients with a normal immune system. The National Institutes of Health’s Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, recently awarded 10 projects focused on a variety of diseases and health conditions, including Pappas’, with three-year, renewable awards of up to $500,000 annually. This study will collect data to help scientists understand the risks of contracting Cryptococcus and ways to treat it, in addition to identifying any special vulnerabilities.

“Why do people develop cryptococcosis, especially among those with a normal immune system? That has been a question we’ve worked for years to answer,” Pappas said. “We’ve tried to understand the genetics of risk, and now the current project takes that interest and looks at the epidemiological risk factors for Cryptococcus as well.”

Both forms of the infection will be investigated through what Pappas describes as active surveillance. Patients with otherwise healthy immune systems who wish to participate will be enrolled in a prospective trial, and they will provide blood work and be evaluated.

“This way we can try to get the organism, get genetics drawn, and then follow the patient for two years prospectively,” Pappas said. “If we can identify enough cases and controls, it’s likely that we can tease out some risk that is identifiable.”

For this project, UAB is serving as the principal center, with help from Johns Hopkins and 20 other medical centers in the United States. The work will begin in late May at UAB.

“Our work will address a host of interesting unanswered questions right now that many people have interest in because this disease can be so ubiquitous,” Pappas said.